‘A renewal of grief’: New book shares local reflections on Tree of Life massacre

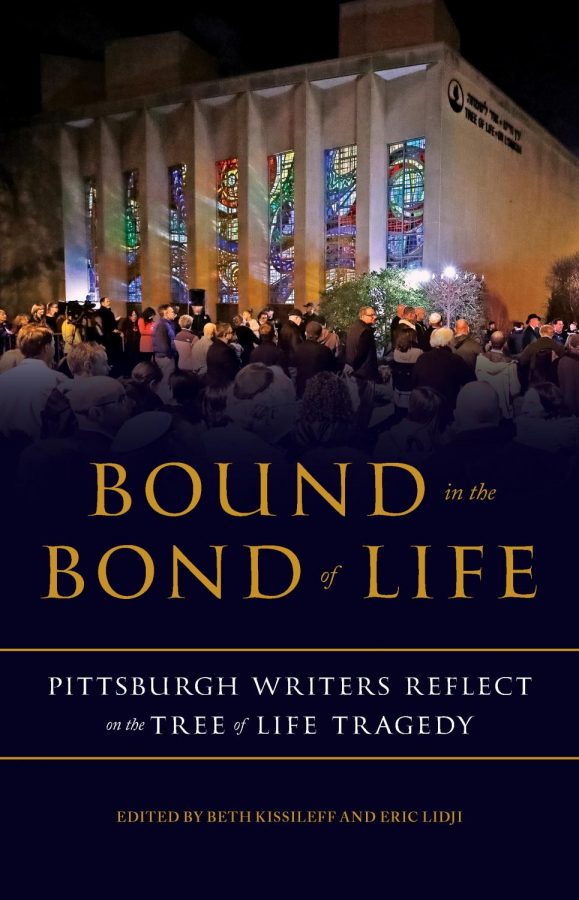

Image courtesy of Beth Kissileff

“Bound in the Bond of Life” is an anthology co-edited by Eric Lidji, an archivist from the Rauh Jewish Archives, and Beth Kissileff, an author and member of the New Light congregation.

October 21, 2020

“In Squirrel Hill, you are always someone’s granddaughter or grandson, son or daughter, mother or father, cousin, coworker, doctor, neighbor or friend,” Eric Lidji reads to the audience. “If New York bestows the gift of loneliness, Squirrel Hill wards against it. To live here requires participation, whether you like it or not. New Yorkers are created every day. We require a lifetime.”

This excerpt comes from “Bound in the Bond of Life: Pittsburgh Writers Reflect on the Tree of Life Tragedy,” an anthology co-edited by Lidji, an archivist from the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives, and author Beth Kissileff. The two spent Tuesday evening answering questions and sharing excerpts like this one — from an essay by freelance writer Molly Pascal titled “Here is Squirrel Hill,” a play off of E.B. White’s “Here Is New York” — at a livestreamed event held by City of Asylum.

The Tree of Life massacre, which took the lives of 11 Jewish worshipers, occurred on Oct. 27, 2018, in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood. The worshipers belonged to the congregations of Dor Hadash, New Light and Tree of Life*Or L’Simcha, which all used the Tree of Life building. The massacre remains the worst anti-Semitic attack in the nation’s history.

Lidji and Kissileff took turns reading excerpts from each of the book’s three sections. Though the essays all tell their own story, the co-editors said together they take the reader through Squirrel Hill, the immediate impact of the massacre and the beginning of the healing process for community members.

According to Lidji, the anthology — which releases Oct. 27, two years after the Tree of Life massacre — features a number of essays and poems that commemorate the lives of those lost during the massacre and helps to amplify the voices of Pittsburgh writers as they examine the effects of what happened.

“Part of the point of doing it is to say to people, in relation to this event, if you feel like you have a story to tell, it’s OK to speak that story and to talk about it, and you should feel that you have permission to talk about it if that’s helpful for you,” Lidji said.

Kissileff, a member of the New Light congregation, said she first had the idea to write the book after she travelled to the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, alongside members of New Light and East Liberty’s Rodman Street Baptist Church congregation. Nine Black worshippers were killed in 2015 at the Charleston church by a white supremacist.

“I asked people to write something about the trip,” Kissileff said. “I was thinking about how valuable it was for people to put their experiences into writing, and thought that it would be interesting to have an anthology.”

Kissileff said she approached Lidji, who was working on cataloguing artifacts from the massacre, about creating a small work that combined the texts and objects. But Lidji said he felt that highlighting the voices of people who had intimate connections to the massacre would help amplify local experiences and stories.

“There are journalists who covered it, people who were members of those congregations, people who had intense emotional experiences which gave them a unique perspective or people who have their own life experiences or through their professional responsibilities have become involved [in the book] in some way,” Lidji said.

Kissileff said she thought focusing on local voices was a crucial aspect of their work, because much of the national media coverage surrounding the massacre missed the nuances of what the experience was like for community members and victims.

“The thing is that when a national media person comes in, there can be reporters that are fantastic and talk to a lot of people,” Kissileff said. “But there are still certain things they’re going to miss, and also, often they try to shape the story in a particular way.”

Lidji said he hopes that by regaining control over the local narrative, the anthology can discuss the raw emotions felt by the community, while also encompassing larger discussions around gun control and combating white supremacy.

“Those big conversations are still happening about what this means and what are our responsibilities,” Lidji said. “But there’s also another conversation, which is personal, and that personal conversation is very different for different people.”

The first section, titled “Here is Squirrel Hill,” opens with Pascal’s essay describing the neighborhood, or as she calls it, the “urban shtetl” of Squirrel Hill. She describes the bustling streets, various eateries and the strong community she grew up in.

Kissileff followed by reading an excerpt from journalist Ann Belser’s essay titled “The News Next Door.” Unlike Pascal, Belser — who was walking her dog past the synagogue when the first shots rang out — reflects on the way Squirrel Hill changed that day.

The second section, called “Finding the Vessel,” features stories about finding objects to anchor oneself to through the grieving process. Lidji read an excerpt from Adam Shear, an associate professor of religious studies at Pitt, in which Shear struggled to balance vulnerability and the rigidity of his academic work. Kissileff followed with a reading of an essay and poems by Arlene Weiner, a poet and playwright, that confronted her emotions on the day of the massacre.

“I marked myself ‘safe’ on Facebook when the alert came — active shooter in my neighborhood,” Kissileff read Weiner’s words aloud. “Is ‘safe’ a lie if you want to believe it?”

The final section, “You Will Get Through It,” was named after a line in an essay by Linda Hurwitz. Hurwitz’s daughter, Karen Hurwitz, was murdered in 1989 at their home in Squirrel Hill. The Tree of Life massacre occurred 29 years after her death, to the date. Hurwitz reflects on the emotions she felt, both about her daughters death and the events of Oct. 27, 2018.

“Always, certain dates, anniversaries, associations trigger a renewal of grief,” Kissileff read Hurwitz’ words aloud. “However, as my wise mother and father said, ‘You will get through it.’”

The book features essays on similar topics as these while highlighting the nuance of local voices. Chloe Wertz, a publicist for the University of Pittsburgh Press, said she felt these stories offered a way for the Pittsburgh community to find some solace.

“I think what’s really beautiful about this collection is that you see a coming together of local voices just trying to make sense of a horrible tragedy in their backyard,” Wertz said. “There is a healing process after a tragedy of this scale, and only Pittsburghers can really explore what that healing looks like.”

Though Lidji said he believed that making narrative sense of the events at the synagogue was central to the book, he noted that the process of writing and editing the essays was painful for him and others.

“It was not a cathartic experience,” Lidji said. “It was actually very painful for us and for a lot of the writers as well. One of the things I like about writing is that it helps me make sense of things, and I don’t think I’ve made sense of things.”

Kissileff said her essay, “Honey From the Carcass,” — which alludes to a story from the Book of Judges — allowed her to express her desire to find something good in all of the trauma. She said though she didn’t find healing, she felt that writing gave her a sense of agency.

“The trauma is still going to be there,” Kissileff said. “So, I’ve tried to do some things to bring something positive and sweet out, despite the fact that the trauma is still there.”

Both editors agreed that the project is far from complete, and discussed other authors they wished to include, but didn’t — either because they didn’t have the space or it was too difficult for those writers to process the events that occurred at Tree of Life.

Kissileff said she hopes readers will find meaning as they read the anthology. She said though she realizes not everyone is as closely connected to the massacre as the authors are, sharing these narratives is valuable to everyone.

“This book is not about the grimness or the gory details. This book is about how people respond, how people cope, how people find meaning, how people make their way through an event like this,” Kissileff said. “And I think anybody that’s coping with any kind of difficult event will find something of value and of meaning in the book.”

The contributors to “Bound by the Bond of Life” are Eric Lidji, Beth Kissileff, David Shribman, Molly Pascal, Andrew Goldstein, Tony Norman, Ann Besler, Kevin Haworth, Avigail Oren, Brooke Barker, Laura Zittrain Eisenberg, Lisa Brush, Susan Jacobs Jablow, Peter Smith, Adam Shear, Daniel Yolkut, Arlene Weiner, Jonathan Perlman, Campbell Robertson, Toby Tabachnick, Abby Schachter, Jane Bernstein, Barbara Burstin and Linda Hurwitz.