Student-led discussion zooms in on Venezuelan migrant and refugee crisis

Screenshot courtesy of CLAS PITT | Youtube

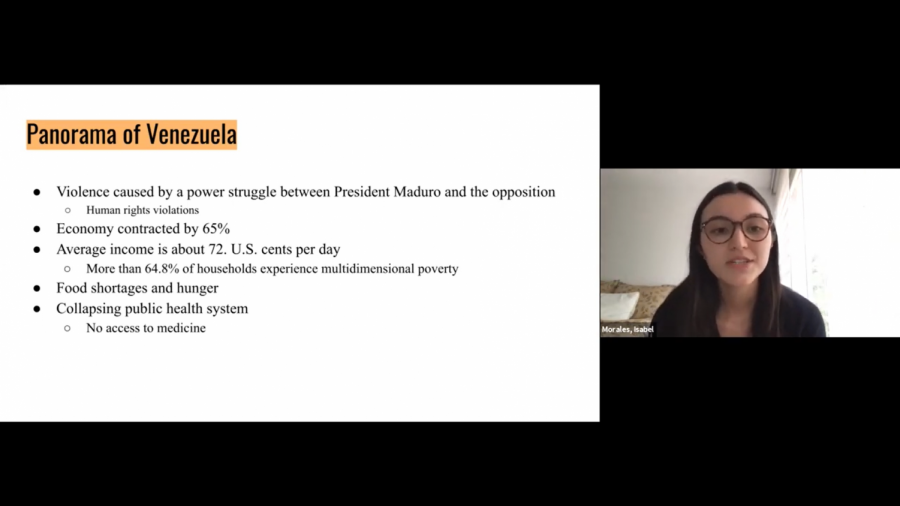

Isabel Morales, an international student from Colombia, led a discussion Friday afternoon about her article she published on Panoramas about the Venezuelan migrant and refugee crisis.

November 9, 2020

As an international student from Colombia, Isabel Morales is trying to bring attention to a humanitarian crisis that has not been publicized much on social media and hits close to home.

Morales led a discussion Friday afternoon about her article covering the Venezuelan migrant and refugee crisis. The article was published in Panoramas, Pitt’s online, student-led publication dedicated to news, research, culture and art of Latin America, the Caribbean and Latinx Caribbean diasporas.

The event was the fourth in a series of roundtable discussions led by Panoramas student interns who are working on their own research through the Center for Latin American Studies. Morales opened her presentation with an image of the Venezuelan-Colombian border from Julián Lineros, who works alongside Morales’ father. Morales said she hopes to bring light to the issues Venezuelan migrants are facing.

“I wanted to share this because I think it tells you a lot about the situation these [migrants] are in. Most of them are traveling on foot, and they’re not only traveling to neighboring countries like Colombia and Brazil, but also to countries further away, like Peru, Ecuador and Chile,” Morales, a sophomore economics major, said. “Even to get to relatively close cities like Bogotá, it can take weeks.”

Morales said the Venezuelan refugee crisis is different from others. Although the crisis is not due to conventional war or conflict, the conditions the migrants face are not too different from those that people in an active war zone face. Morales said more than 4.2 million Venezuelans — 12% of the population — have migrated to date, causing the humanitarian crisis to become one of the worst in the world.

“Not only are they traveling on foot, but they’re traveling under horrible conditions, where a lot of them don’t have money to pay for food or shelter,” Morales said. “Essentially, they’re traveling through the mountains, which is a very dangerous journey overall, and they risk encountering violence on the way.”

According to Morales, the violence in Venezuela is caused by a power struggle between President Nicolás Maduro and the opposition. Though the United Nations has stepped in to implicate Maduro and other high-ranking officials for human rights violations, international financial support for the affected population has been limited. Morales said even though the crisis in Venezuela is on par with the number of people affected in Syria, the amount of support has been drastically lower.

“The Venezuelan crisis is becoming one of the most underfunded in modern history, and it’s currently on pace to surpass the number of refugees in Syria,” Morales said. “In response to the Syrian crisis, the international community contributed $7.4 billion in the first four years, while funding for the Venezuelan crisis only reached $580 million.”

Manuel Roman-Lacayo, associate director of the Center for Latin American Studies, used the discussion period to further the topic of underfunding for the Venezuelan migrant and refugee crisis.

“What’s behind the relatively underfunded support for Venezuelan migrants as opposed to refugee crises elsewhere?” Roman-Lacayo said.

Morales said she believed the international community just does not have enough to support all the different refugee crises right now.

“There are other humanitarian crises happening in the world, like the ones happening in Syria and south Sudan,” Morales said. “I think they start to prioritize, in a way, by which ones have more devastation or a larger death toll. Because the Venezuelan crisis isn’t due to conventional war, the devastation is probably not the same.”

Participants also took to the roundtable to share their own experiences. Oscar Hung, a sophomore finance and global management major, is a Venezuelan migrant. He said one of the glaring problems with maintaining the peace is the people’s lack of faith in their government.

“When you’re talking about a government that only has 15% approval, and it has a lot of ties with drugs, terrorism, you have to be really careful with where you’re sending money,” Hung said. “You want to make sure that the money is going to someone that can use it to make an impact, not just someone that will put it back into illegal activities.”

Morales said she found it inconceivable that a country like Venezuela — one so rich in natural resources, especially oil — became so mismanaged and corrupted. Joyce Pagan, a graduate student in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, said she recalls seeing the discrimination against Venezuelan people while studying abroad in Ecuador for a semester.

“It was my second week in Ecuador, and a Venezuelan man stabbed his pregnant Ecuadorian girlfriend on the streets, in front of police, and no one did anything,” Pagan said. “But suddenly, it was every Venezuelan’s fault, and there were massive protests that got a little violent. Every man, woman and child that was Venezuelan was blamed for it.”

Pagan said her own host family told her to stay away from Venezuelans and that the hatred is justified by saying Ecuador is already suffering economically and can’t handle Venezuelans.

“It kind of parallels the rhetoric in the United States, like, ‘Go back to your country, it’s not our problem,’” Pagan said. “If we saw an individual that was not white-passing and was brown, begging for money, we were automatically to assume that they were Venezuelan.”

Morales said she was disappointed to see that ever since the Venezuelan crisis has started, it has only been linked to crime, hate and other negative ideas. As for the question on most Venezuelan’s minds — when the crisis will end — Morales said there’s no definite answer.

“The president continues to deny that a humanitarian crisis exists,” Morales said. “The necessary funding and increasing awareness about the magnitude of this crisis is crucial to ensure the protection and security of these refugees.”