Panel discusses COVID-19 demographic trends, vaccination hesitancy

Five people representing the Allegheny County Health Department and the Black Equity Coalition spoke Monday morning at “Coffee and Conversations: COVID, Vaccines and Vaccine Hesitancy – what’s happening in Allegheny County.”

October 19, 2021

It is important to observe demographic trends when analyzing COVID-19 testing, but LuAnn Brink said it becomes difficult when a patient’s race is not included in the data.

“COVID cases come in as laboratory reports to us. They don’t necessarily know a person’s race or ethnicity. They know date of birth, result and last name,” Brink, chief epidemiologist in the Bureau of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Allegheny County Health Department, said. “We were seeing people pass away and we didn’t even know what race they were.”

Through working with several health care systems and the ACHD’s Department of Human Services, the health department ultimately collected this data from 90% of cases with missing race and described trends within it.

The “Coffee and Conversations: COVID, Vaccines and Vaccine Hesitancy – what’s happening in Allegheny County” event Monday morning featured a panel of five presenters representing the ACHD and Black Equity Coalition. Panellists discussed vaccination rates and hesitancy, and whether these problems disproportionately affect subgroups such as senior citizens or people of color.

ACHD representatives spoke about current progress and data in terms of Allegheny County COVID-19 vaccine rates and community efforts to improve them.

Annie Nagy, administrator for workforce development and training programs at the ACHD, said a small amount of vaccines were initially available in January. At that time, the ACHD centered vaccination efforts on people above the age of 65 — the population most affected by COVID-19.

“We took all the senior high-rises in Allegheny County, which is 108, and specifically focused our efforts there,” Nagy said. “Every single day, we would go to a different senior high-rise, let them know we’re coming and we would vaccinate anyone in the building that wanted to be vaccinated.”

As vaccination rates increased and more vaccines became readily available, Nagy said the ACHD focused vaccination efforts throughout communities and specific locations within them, such as farmers markets and fairs. The ACHD began looking for places where people were comfortable and willing to go to get vaccinated.

“We started working with the library system, both the Carnegie Library System and the greater county library system,” Nagy said. “We were also working with the county executive’s office to find contacts in other communities that may be a little further out. We started doing farmers markets, night markets, community events and community fairs.”

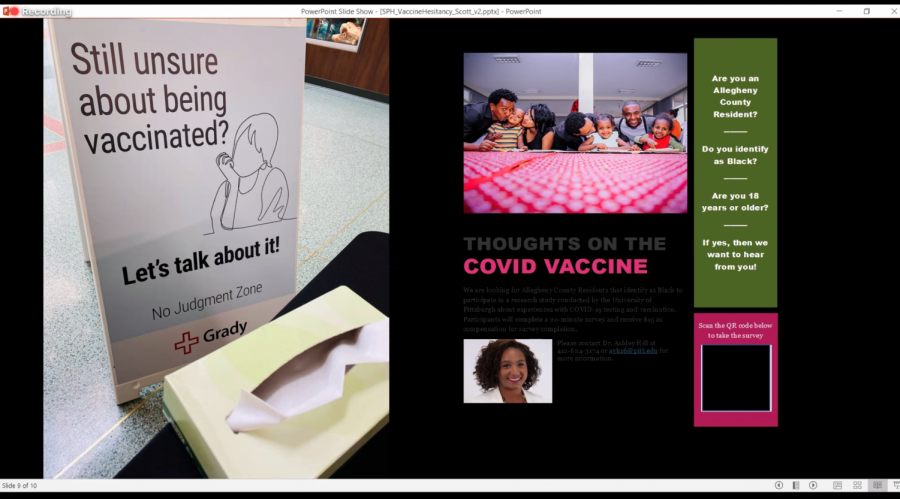

Representatives from the Black Equity Coalition also spoke about the progress they’ve made and challenges faced with vaccination rates and efforts in different communities. Ruth Howze, the BEC’s community coordinator, said the organization does various forms of community outreach in various locations, one being public schools.

According to Howze, the BEC has an existing relationship with the Woodland Hills School District, an area where she said vaccine hesitancy is high. After talking with the superintendent, Howze said the BEC decided the best approach to combat vaccine hesitancy would be through familiarity.

“We are going to bring in Black health experts and clinicians, so people having hesitancy and trust issues can see somebody that looks like them, can most likely resonate with some of their experiences and can have candid conversations,” Howze said. “Not to promise that they will trust them, but it is more likely.”

Howze said another way the BEC engages in community outreach is by sponsoring community health and wellness activities. She said a Homewood resident told her that if the BEC had not provided the vaccine to them, they wouldn’t have gotten it, which Howze said was a “big deal.”

Mistrust is one of the main challenges the BEC faces in fighting vaccine hesitancy, according to Howze. She said the Tuskegee experiment — an unethical syphilis study done by the U.S. Public Health Service and Tuskegee Institute that involved 600 Black men — was an example of a past event that caused medical mistrust among minority populations.

Howze said mixed messages from public officials also contribute toward mistrust.

“Fauci would say something, then somebody else would say something, then our ex-president would say something else,” Howze said. “Recently we saw the new director of the CDC come out against her own panel of support. It’s confusing and no wonder why people are having a difficult time deciding.”

Howze said at this point, the people who want to be vaccinated have already been vaccinated. But she said the BEC works to educate and convince people who are still hesitant toward the vaccine.

“I try to use trust and authenticity, familiarity, initiating conversation, being myself and confidence about the information I know,” Howze said. “I’m sticking to the science and not adding any fluff to it. I use peers and other trustworthy people to argue my case.”

A previous version of this story referred to LuAnn Brink as chief epidemiologist in the Bureau of Epidemiology and Biostatistics. She is chief epidemiologist in the Bureau of Data, Reporting and Disease Control. The article has been updated to reflect this change. The Pitt News regrets this error.