“Are you going to pay attention or are you going to talk?” Marion Damick addressed the Allegheny County Jail Oversight Board during her public comment on Sept. 7. This month’s meeting happened to be on her 98th birthday. But before enjoying her cake, Damick urged the board to seek solutions to glaring problems in the Allegheny County Jail. Damick has attended board meetings for over 20 years to advocate for incarcerated individuals.

In contrast, County Executive Rich Fitzgerald consistently fails to attend the jail oversight board meetings, despite being statutorily required to. In April 2021, a group of local organizations and leaders signed a letter demanding his presence at meetings, arguing that it’s a responsibility he has “routinely and deliberately ignored over the course of more than a decade.” Now, over two years later — still, no Fitzgerald.

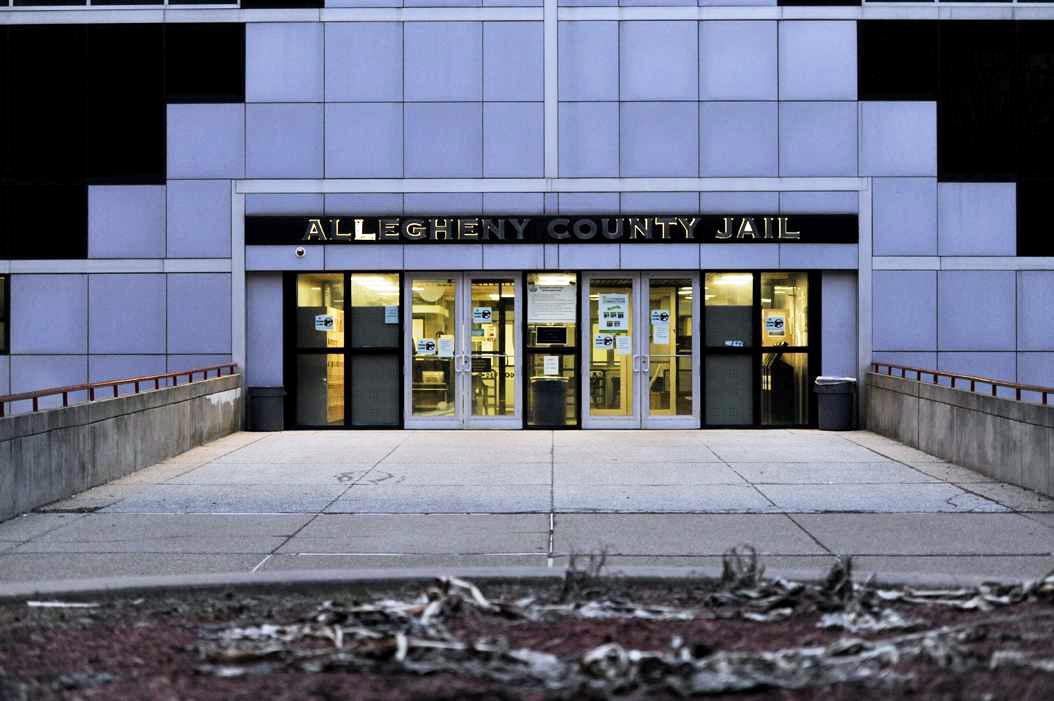

The Sept. 7 meeting marked the departure of the jail’s warden, Orlando Harper, who is retiring before the next county executive is elected. He is frequently scrutinized, and for good reason. Conditions in the jail appear to be getting worse and worse, and many incarcerated individuals have died under his care. At Thursday’s meeting, community leaders and oversight board members questioned and condemned his continued decision to strip search children in the jail.

During her public comment, Jodi Lincoln of the Prison Book Project reminded Oversight Board members that, several months ago, she and other community members brought them research on child strip searching. “Many of you expressed serious concerns at the time with the strip searching of children, and rightfully so, but as is typical of this board, you have failed to act,” she said.

Tanisha Long of Abolitionist Law Center emphasized that the jail has a full body scanner and therefore has no need to search minors in such invasive ways. “You can stop strip searching children, it’s not hard, especially in a jail with a full body scanner,” she told the board.

In response to criticism about the policy, Warden Harper argued that, “Juveniles coming into our facility have committed adult crimes.” Board members asked why the scanner couldn’t be used for children entering the jail. “Because the full body scanner is not always accurate at all times, so that’s why we’re still going to continue to strip search until further notice,” he said.

Chief Deputy Warden Jason Beasom chimed in with another excuse — that the state doesn’t allow them to use the scanner for children or pregnant individuals. “It’s similar to x-ray technology, so I’d assume it’s because they don’t want that exposure to the juvenile,” Beasom said.

Terri Klein, a community member on the board, suggested that children could wear lead aprons like patients do for x-rays at the dentist, but jail leadership quickly shut her down.

That was the end of that. No further discussion about less obtrusive and humiliating alternatives, no acknowledgement of the bodily trauma kids face in juvenile detention or the generational and systemic factors that affect their presence there in the first place — such as the school-to-prison pipeline. When the jail administration says things so matter-of-factly, they’re attempting to normalize the atrocities that incarcerated people experience. Do not let them.

Matter-of-factness can turn into glibness very fast, and it frequently seems to during jail oversight board meetings. If you ever attend one, and I urge you to, you’ll quickly experience two realities — the reality that communities sitting in the audience are begging county officials to address, and the false reality that jail administration and board members concoct to justify their inaction.

With it being the last Jail Oversight Board of Warden Harper’s career, more than a dozen representatives from the Pennsylvania Interfaith Impact Network used their public comment time to make recommendations for a new warden. These included a warden who “listens more than talks,” can “understand and empathize with others,” “conceptualize thinking past today” and rejects the “punitive philosophy of intimidation and threats.”

PIIN based these recommendations on data from the Department of Justice and the National Institute of Corrections. PIIN’s Pat Murray offered some benchmarks for the new warden.

“Within one year, the rate of death at the Allegheny County Jail will be no worse than the DOJ’s average state rate,” she said. “At the end of the first year, the intake unit will be staffed according to NCCHC standards. Within the first two months, healthcare staff will no longer be assigned job duties that violate their license.”

Readers, sit with that for a moment. These are goals that the jail should strive to meet. And they are the bare minimum — no, below the bare minimum. How can any of us conscionably believe that a facility like this cares about rehabilitation? Furthermore — none of these recommendations are coming from the jail oversight board, who are instated and paid to hold the jail accountable.

They’re coming from community members and organizations who attend meetings and do research on their own time, who discuss and suggest solutions with urgency. From organizers who set up bail funds and table in front of the jail so that newly released individuals can get food, clothes and resources. From the family and friends of incarcerated people.

1Hood’s Muhammad Nasir spoke to the members of the audience on Sept. 7, “I want to remind my comrades that there is no such thing as a good warden; there is no such thing as a good jail.”

“I invite all of us to imagine an Allegheny County without a warden, and without a jail,” he said.

India studies politics, philosophy, gender studies and social justice. She loves magical realism books, Joni Mitchell’s music and class consciousness. You can write to her at ilk18@pitt.edu.