Your composition is weak.

Four years of unrelenting critique still echoed through his head in a cacophony of unimpressed sighs, dismissive glances, and outright ridicule.

Where is the passion? This work has no soul.

During school, he’d recoiled from the constant scrutiny of his work; now, he let these bitter memories flood his mind, fueling the fire of his ambition.

You’ll never make it in the art world.

For a time, it had seemed his professors and peers were right. Despite extensive study of the masters — constantly seeking to understand what had made their work persist across the centuries while so many others faded into obscurity — and laboring in the studio for 60 hours a week perfecting his own technique, his efforts were never enough. His rightful place was not within a museum or a gallery, but rather in a lonely shoebox apartment, shuffling to and from his job where he ran burgers and fries to whining children and exhausted parents for pennies.

It turned out “starving artist” did not just imply physical starvation — he felt his passion, his creativity, the very essence of who he was withering under the crushing weight of the accumulated bills and past-due rent. He sensed he was running out of time.

For months, he had been working on a piece. It had started small, a few dabs of paint on his last empty canvas one night after work. But then he continued, painting in defiance of his petty art school critics and the logical urge to pick up extra shifts to make rent and the world that so vehemently hated those who wished to capture its beauty in charcoal and watercolor and clay. He began to spend all his free moments in front of the canvas, painstakingly mixing colors with a broken palette knife and expertly sweeping them across the portrait slowly taking form.

He became obsessive, spending two days perfecting a single shade of blue. He called off work once, twice, three times; then they told him he need not call again — he was done. The world narrowed to himself and this tiny, cramped room and the canvas, a tablet onto which he was carving his masterpiece. It demanded everything — all his talent, passion, ambition, soul.

He grew weaker, hands trembling as he rinsed his brushes. He stopped standing, instead opting to sit hunched before the canvas on an old stool. Hunger gnawed at him; he licked mouthfuls of paint from the tube when the pangs became unbearable. He slept fitfully and then not at all, compelled to finish the portrait before the portrait finished him.

The moment arrived for final touches. He completed the strong bridge of the nose with a final flourish of bronze and felt his own begin to tingle and bleed, a crimson rivulet running down his now-pale skin.

As he outlined the sweeping curve of the lips on the strong jawline, he tried to cough and found that his paint-stained lips would no longer open. It seemed they had been fused shut.

He captured the light reflected in the regal eyes, so brown they were almost black, shadowed like the darkness that rapidly eclipsed his sight and veiled the canvas from view. He panicked momentarily as blindness overtook him. But he knew this portrait like the back of the hand that clenched the brush in a firm but trembling grasp. Besides, there was only one remaining element — the artist’s signature.

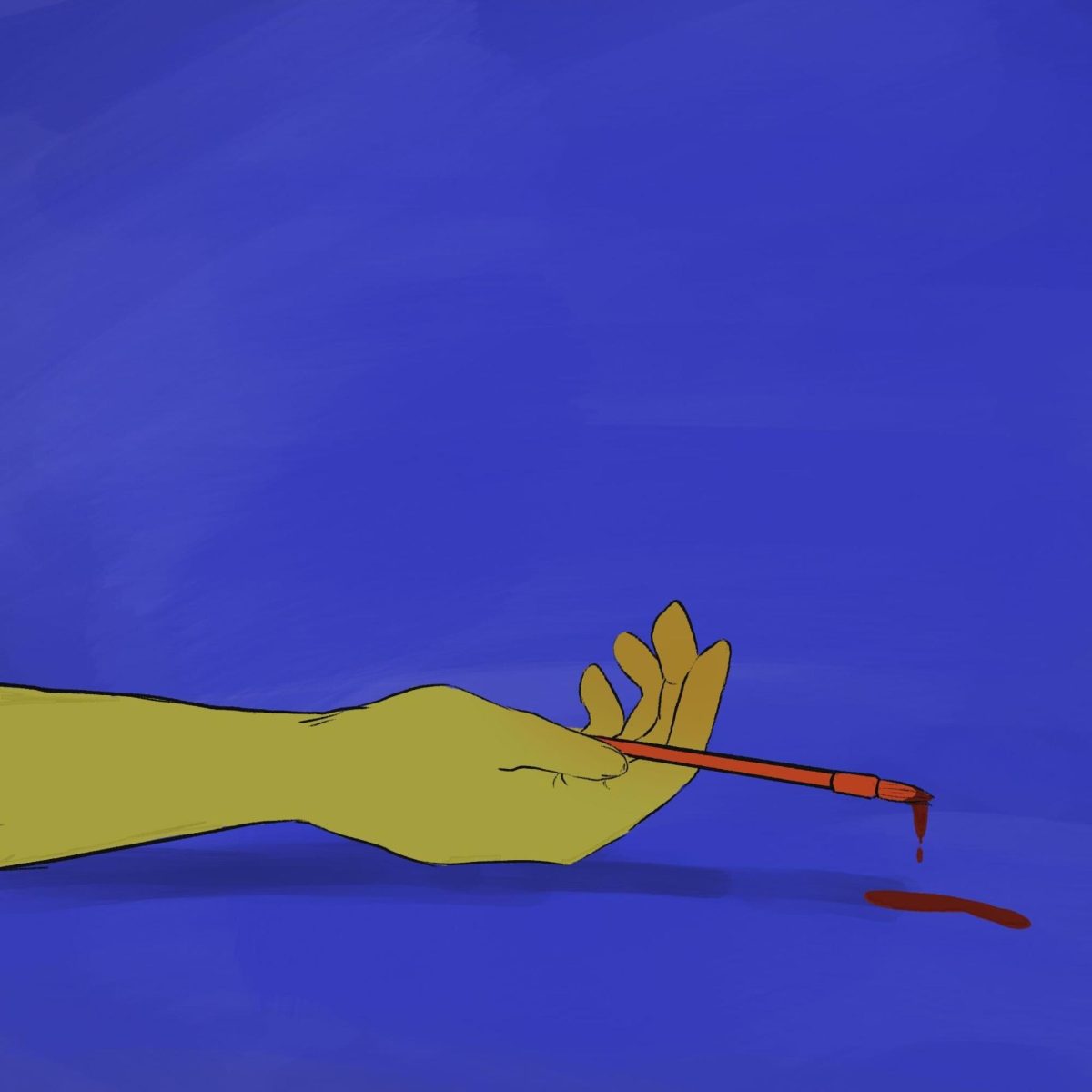

Shuddering, breathing raggedly, blood still dribbling from his nose, the blinded artist raised his brush to the canvas for the final time and signed the portrait in scrawled, looping cursive.

The paintbrush clattered to the floor, the lifeless husk of its spent owner close behind.

***

The painting sold for $50 million.

A portrait rendered in the exact likeness of its creator, it was lauded as a masterpiece and one of the greatest works of realism ever painted. Of course, its backstory — a brilliant artist, a true genius, found dead beside the very work in which he would be forever immortalized — added a certain romance and intrigue the art world found irresistible.

They said his ability to capture himself, his very essence, within the portrait was unparalleled.

It was almost uncanny, in fact. The way the smile seemed to almost widen if you watched for long enough. The way the folded hands seemed to imperceptibly shift position. The way it felt, as you gazed deep into those sharp black eyes, that they were staring right back.

It was almost as if the painting had a soul.