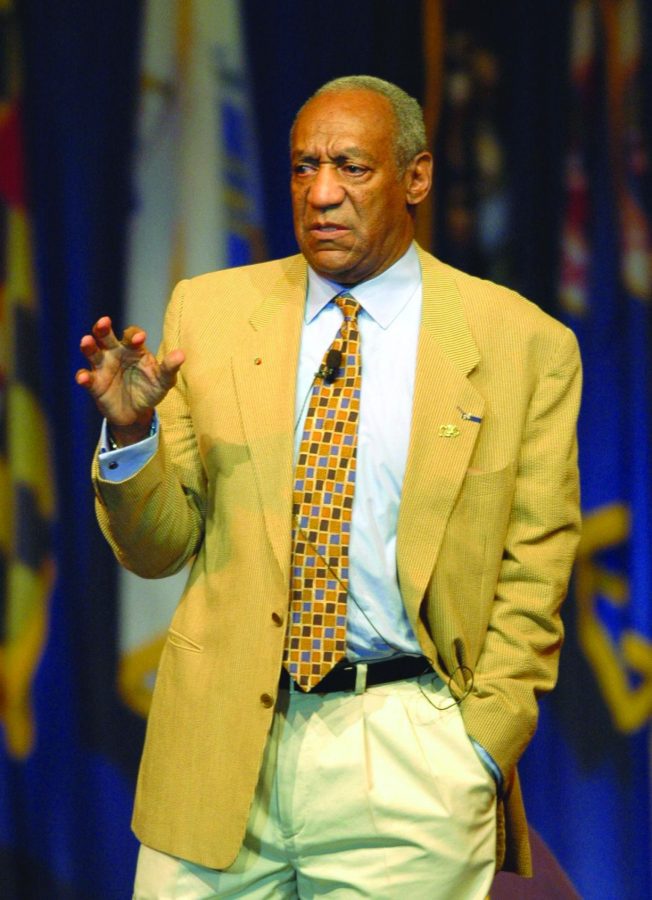

Editorial: Cosby’s allegations reflect reality of rape culture

November 24, 2014

We revered Bill Cosby. He was a father figure, a neighborhood hero and an icon in the mass consumption of black television.

We associated his image with laughs, ornate sweaters and Pudding Pops. We admired his unwavering commitment to moral values.

It turns out we were wrong.

Darker shades of the entertainer’s glorified past have reclaimed national attention in the last few weeks, though they didn’t garner a footnote in his nearly 500-page biography published this September. As these obscene details emerge, our pleasant memories dissipate as we attempt to grasp Cosby’s connection to an ongoing ailment of our society — sexual violence.

Within the past few weeks, mainstream media has stirred public horror at a string of lingering sexual assault allegations against Cosby. Sixteen women have shared accounts accusing the 77-year-old comedian of sexual assault or rape, in some cases preceded by drugging, between 1965 and the mid-2000s, according to The Washington Post.

As our generation grapples with how to address sexual assault, a horror we barely had a name for in political discourse prior to the 1970s, this news rings even more shrilly.

While there has been a rise in reports of sexual assault since the ‘70s, the percentage of reports is still dismal. Only 40 percent of rapes are reported, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, while only three out of 100 rapists face imprisonment.

Cosby’s lawyers and media relations personnel have denounced the claims, calling them fantastical and decades-old. Conversely, the women’s reasoning for keeping quiet or not pushing harder in earlier lawsuits overlap: They were hesitant to take on a powerful celebrity, or they were too traumatized to defend their claims before an unbelieving audience.

We’ve seen this scenario before.

It’s an all-too-familiar narrative that has shaken college campuses and drawn a magnifying glass over how they address sexual assault. It’s come in waves of prominence, ranging from the Jerry Sandusky scandal at Penn State to the ongoing rape accusations at the University of Virginia.

A common thread connects all of these cases: We’re more inclined to rescue the accused than to empathize with the accuser.

We have a problem with shame. Institutions cautiously give any credence to claims, including sexual violence, which may undermine their reputation.

Quick to demand evidence, we’re eager to believe the accusations are false. In reality, only two to eight percent of reported rapes are false accusations, according to the National Center for the Prosecution of Violence Against Women.

We shouldn’t be so eager to shirk blame and protect our image that we fail to seriously consider claims of sexual violence. Why were these claims against anyone from Cosby to Sandusky previously reduced to mere paragraphs, or buried records, when they should have warranted headlines?

We can retain the innocent-until-proven-guilty judicial procedure. But let’s discard the social and cultural attitudes that trigger skepticism of accusations before compassion, understanding and an urgency to help accusers.

We don’t want to live in a world where we shame women who come forward with accusations of sexual assault. Let’s not cloud the victims’ stories anymore.

We have allowed such indifference out of convenience. A pedestal of fame and fortune allowed an accused sex offender to acquire a television contract just this year. A university’s prestige and reputation have a higher priority than the number of students who come forward saying they were raped on campus.

With today’s technology, it’s becoming more difficult to escape the whirlwind of public outcry on social media that surrounds any scandal. The usual arsenal of public-relations maneuvers to defeat accusations of criminal activity miss their mark.

We should use professional and social media to seek justice. An onstage crack by Hannibal Buress on Oct. 16 calling Cosby a rapist prompted an uproar on Twitter, drawing levels of awareness that weren’t even possible a decade ago.

But, fortunately, today it is possible. We can hold leaders and institutions accountable for their actions through a plethora of media.

Cosby’s alleged actions over the past few decades can’t be changed, but our attitude toward the gravity of sexual abuse can. We can work to ensure that victims everywhere can live in a society that respects them and their rights.