CDC unprepared for Ebola risks, must change protocol

October 16, 2014

Don’t panic — according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, we can only contract Ebola through contact with bodily fluids.

Yet, considering recent events, maybe we should question the CDC’s reassurances.

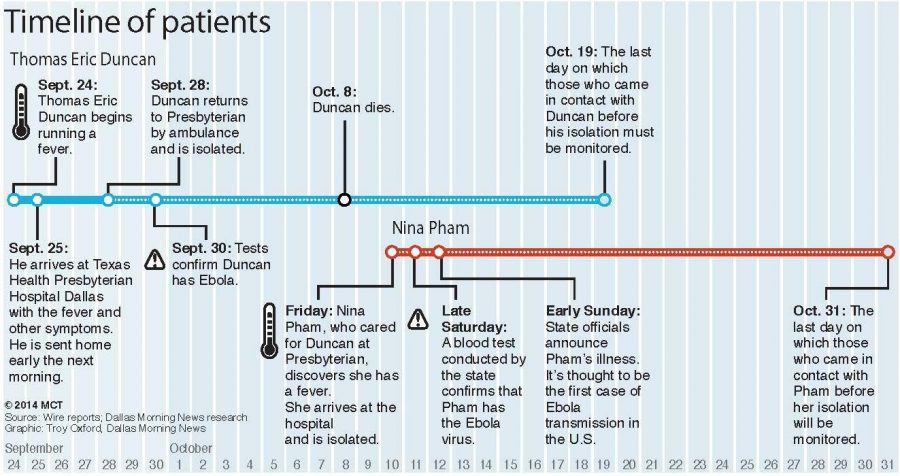

When Thomas Eric Duncan became the first person in the U.S. to have Ebola, the CDC assured that the situation was under control — perhaps because Duncan was originally infected in Liberia.

Unfortunately, Duncan died from the disease and, on Oct. 12, one of his attending nurses, Nina Pham, tested positive for the virus. The diagnosis marked the first case of Ebola transmission to occur in the States.

Last Wednesday, it was confirmed that a second nurse from Texas also tested positive for Ebola. Soon after developing symptoms, she flew on a commercial flight from Cleveland to Texas along with 130 other passengers — the CDC originally gave her permission to do so, even though she told them that she had a low-grade fever.

So, does the CDC really have the situation under control?

National Nurses United — the largest union of registered nurses in the country — says no. According to their survey of over 700 registered nurses across 31 states, U.S. hospitals are far from prepared for an outbreak.

According to the survey, 80 percent of nurses reported that their hospitals have made no communication regarding the potential admission of patients infected with Ebola. In 87 percent of hospitals, nurses received no education on Ebola or the relevant protocols. One third of hospitals did not have adequate eye protection or fluid-resistant gloves and gowns.

U.S. hospitals, it seems, have so far underestimated the havoc that Ebola could wreak upon the population. This is primarily due to the CDC undermining the virus. In a recent press release, CDC chief Dr. Tom Frieden blamed the first nurse diagnosed with Ebola for contracting her own infection.

“Clearly there was a breach in protocol,” he told CBS.

Maybe this “breach in protocol” happened because of a lack of an actual protocol regarding Ebola for hospital employees to follow. It’s mind-boggling that Frieden blamed a nurse’s own “self-monitoring … as per protocol,” for contracting Ebola when she was just performing her assigned duties.

According to authorities and fellow nurses, no breach in the original affected nurse’s conduct was noted, making Frieden’s statement premature and unprofessional.

Frieden and the CDC proved amateur yet again in dealing with Amber Vinson, the second nurse to contract the virus. Nurses who assist Ebola patients are not supposed to travel via commercial transportation, but Vinson boarded a flight between Cleveland and Dallas on Tuesday shortly after treating Duncan — the CDC gave her permission because she was showing no other signs of Ebola, other than the fever she had.

Furthermore, an analysis of the treatment Duncan received reveals major mistakes.

When Duncan started displaying symptoms of Ebola in late September, he went to the hospital. Despite telling the hospital staff that he had recently been in Liberia and was running a 103-degree fever, he was sent home with antibiotics and painkillers.

Duncan’s situation, unfortunately, did not improve, and he later died in an isolation unit of a Dallas hospital.

A supposed flaw in an electronic records system did not document that Duncan had been in Liberia, where Ebola has affected more than 4,200 people. Was that enough reason to write his symptoms off as arbitrary, though?

In the span of time that Duncan was released from the hospital, he may have unknowingly infected people — 48 people within the Dallas community are currently being monitored.

To prevent more cases, the CDC should take more precise measures in light of the epidemic. The manner in which the CDC has treated subsequent diagnoses of Ebola in the U.S. shows a pattern of neglect.

In press releases, CDC officials always make sure to tell reporters how hard it is to catch Ebola instead of notifying the public on how to remain safe just in case a fluke happens — and, apparently, they do happen. The CDC is more concerned with looking like they know what’s what, rather than protecting the public.

While only one case of Ebola has originated in the U.S. so far, Texas is not an island. Almost within a month’s time, Ebola has transmitted from Duncan to hosts who have never been to Africa.

The CDC is being reactive, rather than proactive. How many people need to be infected with Ebola before they start to create a better prevention system?

Luckily, National Nurses United has made a few suggestions in their dissenting statement against the CDC. Nurses want a comprehensive prevention plan, including a full training of hospital personnel. They want effective protocols and the appropriate training materials — these include Hazmat suits and properly equipped isolation rooms.

The Ebola pandemic is much more serious than what the CDC is making it out to be. No, you cannot breathe in Ebola particles and turn into a zombie, but it isn’t impossible to contract the infection. That is the basis the CDC should center their preparation on — no one can just assume that the U.S. can handle this disease just because it is a part of the developed world.

All things considered, if hospitals aren’t appropriately trained or funded for Ebola and an outbreak occurs, we’re in trouble. In this instance, it’s better to be over-prepared against the virus.

Write to Courtney at [email protected]