Summer Guide: Soto, Mildren adjust to life in the minor leagues

July 15, 2014

Minor league baseball players can begin their careers in a number of places across the country — just ask Elvin Soto or Ethan Mildren.

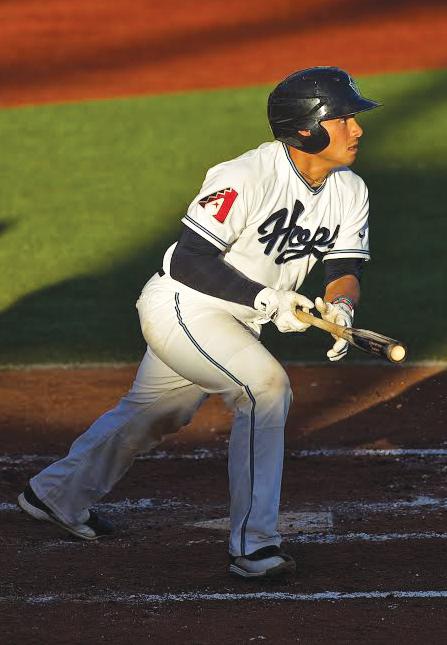

Soto’s’s destination, after getting drafted last June, was Hillsboro, Ore., home of the Hillsboro Hops, the Class A Short Season affiliate of the Arizona Diamondbacks. In this brand new environment, Soto didn’t know anyone at first.

“You have to start building relationships with people all season,” he said.

During his two years at Pitt, Soto would often drive the six hours home to New York City to see family and get a home-cooked meal.

He can’t do that anymore. Soto’s current setup has forced him to grow up — something the catcher has come to appreciate.

“Being on my own, I’m maturing and learning day by day through my experiences,” Soto, 22, said. “I’ve become a man.”

Personal growth is inevitable in this environment, where the safety net of college, with its coaches and support staff and the subsequent structure that has everything laid out, is nowhere to be found.

For Mildren, a former Pitt teammate of Soto’s who pitches in the Minnesota Twins organization and is also in his second professional season, one of the biggest adjustments has been that baseball is now his full-time occupation — a welcome development.

“It’s a lot more self-responsibility and staying on track with yourself,” Mildren said.

Newfound responsibility is the norm for young adults finding their way through post-college life, but minor league baseball is different than the norm with its eight-and-a-half hour bus rides, per diems and wacky gimmicks such as Zombie Apocalypse Night. Players in the minors — with seven levels and a system of player promotion and demotion — have to learn to adapt to new situations both on and off the field.

Soto likes his current arrangement.

“It’s fun. You get to play every day,” he said. “It’s better than working a nine-to-five.”

But it’s still a job, and the working environment of minor league baseball can be challenging, according to Pitt head coach Joe Jordano.

“It is a grind at the lower levels of pro ball,” Jordano said in an email. “There is a lot of pressure to produce. You really have to be prepared mentally and physically for that.”

So far, Soto and Mildren have shown their preparation.

Soto, now in his second season as a Hop, hit .209 with seven RBIs in 45 games last year. As of this writing, in 21 games so far this summer, he’s hit .321 with 10 RBIs.

Mildren made all of his 12 appearances for the rookie league Elizabethton (Tenn.) Twins last season as a reliever, going 1-1 with a 1.65 ERA. As a starter this season with the Cedar Rapids Kernels, he went 3-5 with a 4.03 ERA in 14 appearances.

This season, Mildren began with the Class A Twins affiliate, one level above where he started last year. On July 6, he learned he’d been promoted another level — High Class A and the Fort Myers (Fla.) Miracle.

Mildren packed up his belongings and flew down to Florida the next morning with a teammate, who had also been promoted.

“I was definitely excited to come down here,” Mildren said. “It’s just the beginning now — long way to go.”

Mildren won his first start with his new team on Thursday, going 5 1/3 innings and giving up two runs in a 5-4 win.

He said he handles the constantly changing environment of the minor leagues — where he can be told he’s switching teams and state of residence in an instant — by trying not to worry too much about it and focusing on what he can control, like pitching well in games.

“They can send me up or down, wherever, but mainly it dictates off of me and how I do,” Mildren said.

Still, it’s hard not to notice when someone in the locker room is gone suddenly.

“It kind of sucks when you see guys come and go, come and go, come and go,” Soto said. “Obviously you want to move up and progress but I’m happy I get to play baseball. There are a bunch of kids who’d like to trade places with me.”

With the constant team switching comes varied living arrangements — another part of the minor league experience.

Both Soto and Mildren have stayed with a host family, where they had a roommate who is a teammate. Soto has spent all his time in the minor leagues living with a host family.

While staying with a host family, which volunteers its services, the player doesn’t have to cover housing costs — no small detail when monthly salaries in the minors during the season range between $1,100 and $2,150. Soto said his family feeds him and provides transportation when needed.

Mildren shared an apartment with four teammates last year and had a host family for the past three months.

Not all teams have arrangements with host families, but those who do go through application processes and have to abide by certain requirements. Prospective host families in Hillsboro must live with 10 miles of the ballpark and have a free room and bathroom for the player to use.

Currently, Mildren and his teammate from Iowa are staying in a dorm room at the team’s complex. Teams in the Florida State League have similar living complexes across the state because the Major League clubs and their minor leagues come for spring training.

At some point, the players’ careers will come to an end, but neither one has a set backup plan.

Soto, who left Pitt after his sophomore year and majored in administration of justice with a minor in Spanish, said he wants to finish his schooling when pro baseball ends. He said he has also considered taking the test to become a fireman in the offseason. Mildren, who left Pitt after his junior year and majored in sociology, plans to go back to school and get his degree.

Neither player enjoys thinking about those scenarios, though, because to do so would acknowledge the finite nature of their current occupation.

“You can’t control the future. You can’t control the past. All I can control right now is what I’m doing,” Mildren said. “If you worry too much about the future, it’ll mess with now and it won’t get you where you want to go.”