tUnE-yArDs sports wealth of ideas on new avant-pop masterpiece

May 7, 2014

Many of tUnE-yArDs’s contemporaries — if related article and video algorithms are to be believed — have released albums that critics were hesitant to embrace on the grounds that the artists behind them had “too many ideas.” Similar albums — such as Ava Luna’s Ice Level, Everything Everything’s Man Alive and Max Tundra’s Mastered by Guy at the Exchange — were all just a little bit too much for some people to process.

Interestingly enough, though, all three artists put out relatively pared-down follow-ups, and their former detractors began to cite a process of maturation and refinement, handing out “most improved” medals to anyone who ceased to vex them. But if an artist’s best work is also his or her most boiled-down, then how do you explain an album like Nikki Nack?

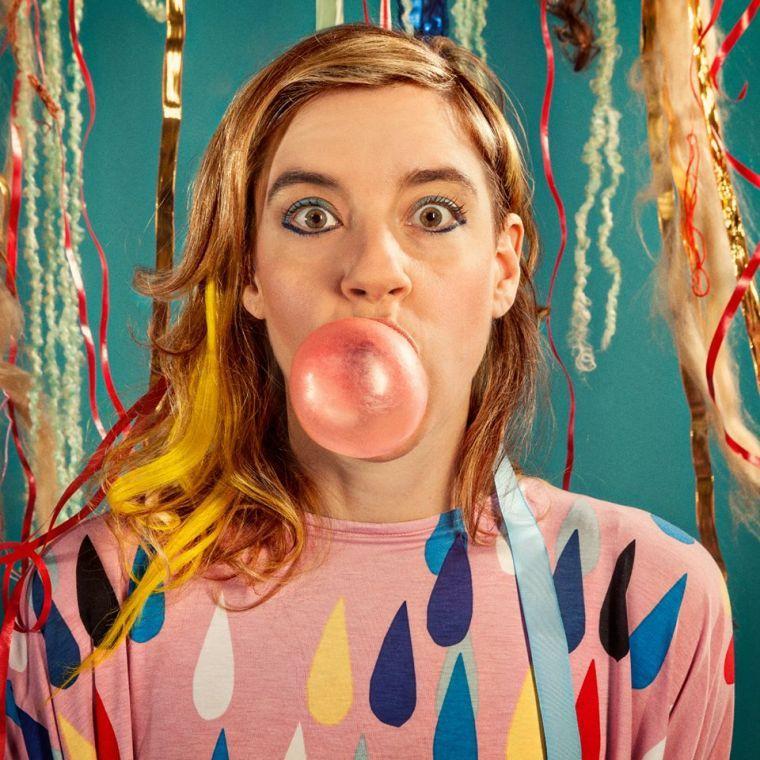

tUnE-yArDs is the recording project of Oakland-via-Montreal singer-songwriter Merrill Garbus, although her bassist and co-writer Nate Brenner’s affinity for off-kilter jazz harmony is becoming an increasingly important element of her sound. Beginning as a loop-based live act in 2006, tUnE-yArDs has since released two albums of tense yet exuberant songwriting fueled by intricate, Afrobeat-inflected drum loops. The 2011 album w h o k i l l, in particular, was lauded for its wild creativity, as well as Garbus’ incredibly versatile behemoth of a voice. But for as off-the-wall as that album was, her third studio effort Nikki Nack is more so, and yet it’s all the better for it.

First, Garbus’s voice has not lost an ounce of its expressiveness since we last heard it, only now it’s being placed in radically different contexts. She tries on girl-group close harmony during the chorus of “Real Thing” and it suits her just as well as the snarling call-and-response, glitchy cut-and-paste and desperate belting that we hear later in the very same song.

But despite her chameleonic, four-octave range, her performances are rarely disjointed, because she uses her vocal acrobatics to emphasize the emotional contour of both the music and the lyrics. When she sings lines like, “Give me your head!/ Off with his head,” she does so with all-caps conviction, and the contrast makes it all the more effective when she delivers lines like, “A thousand roads to injury/ Most of them so smooth it doesn’t feel like they’re hurting me,” with an eerily vacant coo.

Sex and violence have always been tUnE-yArDs’s lyrical M.O., but here, they’re nestled alongside some sociopolitical vitriol to further complicate matters. Nikki Nack invites quite a few new possibilities for expression: frustrated tenderness, prideful desperation and even morose brilliance.

“Real Thing” is a particularly intense experience, which bookends unabashed sexual confidence with tongue-in-cheek lines like, “I come from the land of slaves/ Let’s go Redskins! Let’s go Braves!” She’s capable of conveying many different emotions with her voice and lyrics as if she got tired of each individual feeling, and chose instead to see where they intersect.

Another interesting development on this album is Garbus’s ever-increasing willingness to experiment with rhythm.

“Look Around” pulls its elliptical vocal melody around rigid drums like taffy while the pulsating moans that color the hook on “Wait for a Minute” seem to adhere to no rhythmic logic whatsoever. But don’t let it fool you; absolutely nothing in Nikki Nack is left up to chance. Once you learn to speak their language, the systems that govern these apparently chaotic songs reveal themselves, and you’re given the choice to either peer into or get lost in their twisted logic.

It’s a logic made all the more explicit by tUnE-yArDs’s fortunate, if counter-intuitive, choice to work with some big-name pop producers here, enlisting the help of John Hill (Phantogram, Shakira) and Malay (John Legend, Frank Ocean). They both do an excellent job of smoothing out the discontinuities that naturally arise with an eccentric performer like Garbus, but they also manage to avoid sacrificing any of the sonic quirks that make her music so attractive. They just rein the chaos into tight, perfect pop songs instead of letting it all sprawl out incomprehensibly, which is what allows the music to be so completely bonkers.

Before recording the album, Garbus studied Haitian dance-drumming traditions on a humanitarian excursion to Port-au-Prince. But weeks later, upon returning, she read Molly-Ann Leikin’s “How to Write a Hit Song” with the exact same voracity for culture. And Nikki Nack feels like such an elegant reconciliation of those tendencies.

It’s a hyperactive, pan-global avant-pop masterpiece, on the same scale as its predecessors but somehow even denser. If you thought w h o k i l l had too many ideas, wait until you hear this.