How does a Syrian child turn into a terrorist?

When conflict ravages a region, children bear the consequences. Their families can no longer live in the country they love. They become refugees, and their primary concern becomes survival. Education takes a back seat and violence defines their lives.

In Syria, children are losing their chance to achieve success through education. The mounting crisis and the inadequacy of educational aid paves the way for extremism in the next 10 to 20 years. The international community needs to support the crumbling national education system and expand self-learning programs to protect Syria’s children from prowling extremist recruiters.

Before conflict hit, Syria had one of the highest literacy rates in the world. According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics, from 2008 to 2012, 84 percent of Syrians aged 15 and older were literate. In the same time frame, the primary school net enrollment rate was 99.6 percent.

Those numbers changed significantly once Syria — and Syrian children — fell victim to the effects of war.

A joint 2015 report from UNICEF and the UNESCO Institute of Statistics determined that 3 million children are out of school in Syria and Iraq, where the effects of war have destroyed much of the education system. That means 40 percent of all school-age Syrians are out of school, according to a 2014 UNICEF report.

The joint report found that the conflict has resulted in one in four Syrian schools being damaged, destroyed or converted into a shelter for the military or displaced civilians. The remaining schools lack teachers and supplies and can’t promise safety to their pupils. At least 20 percent of children need to cross active lines of conflict just to get to their exams. Rather than risk getting hurt, many children just stay home.

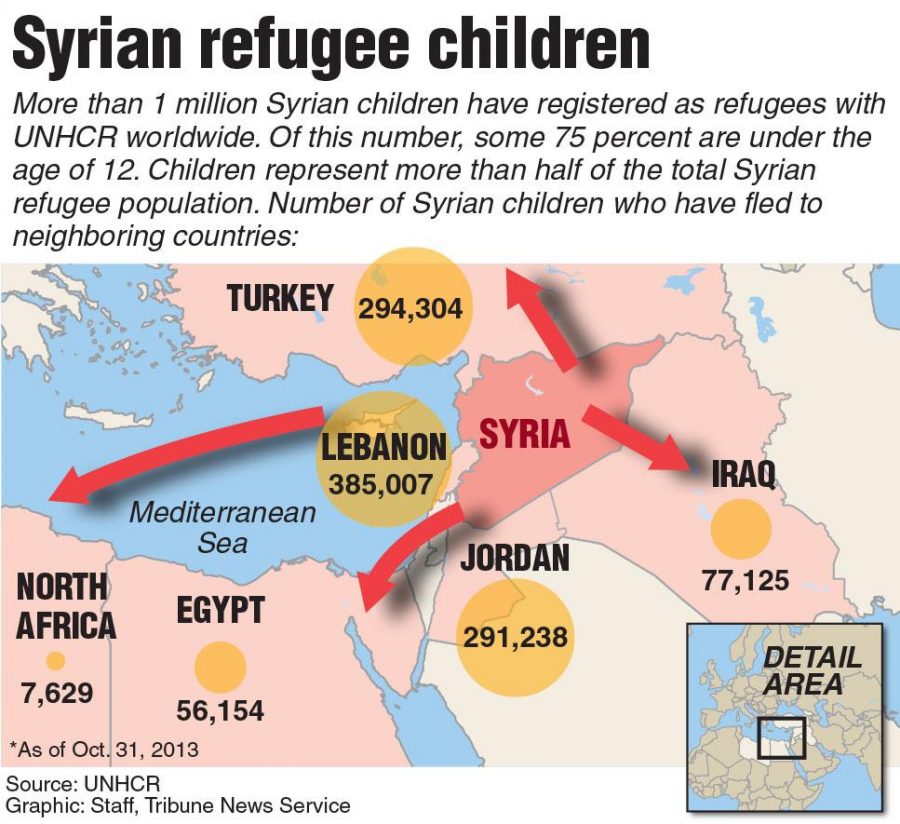

Seven hundred thousand Syrian children are refugees in neighboring countries whose school systems simply can’t handle the extra load or are ill-equipped to teach Syrian children, according to another UNICEF report. Refugee camps in Lebanon, for example, offer a school share system in which state schools run extra shifts to educate Syrian refugee children. However, the system has a limited capacity, and the Lebanese curriculum’s French delivery is frustrating to Syrian children accustomed to Arabic, according to an article written for The Guardian.

The report emphasized that families caught in the conflict identify continuing education as their first priority. While organizations like UNICEF and UNWRA have started initiatives to provide self-learning materials and expand and supply learning spaces — like the UNICEF-supported adolescent-friendly learning spaces (AFLS) — they struggle to fund them.

“We are on the verge of a lost generation of kids,” said Peter Salama, the UNICEF regional director for the Middle East and North Africa, in an interview with the New York Times.

These kids are lost educationally, but they also have the potential to be lost culturally. A parallel trend to the dropping number of children in school, said Salama, is the recruitment of kids into paramilitary organizations.

Syrian dropouts face crushing blows when their limited education begins to dominate a culture that was previously focused intensively on education. Extremist activity hasn’t claimed every impoverished nation, but Syria’s situation is different. Children in Syria come from highly educated families, and growing up in instability represents a drastic change in culture. These changes, coupled with frustration, make them easily attracted to readily available outlets, like terrorist groups.

Extremist groups attract children with limited access to education, according to a 2009 report by the Homeland Security Institute. The report states that lack of education, paired with mental instability, creates opportunities for radicalization.

“The best way to fight terrorism is to invest in education,” said Malala Yousafzai, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate, at the Forbes Under 30 Summit in 2014. She went on to advocate for the international community to follow new policies of aid, imploring, “Instead of guns, send books.”

Other countries and world organizations have invested in the education of Syrian children, but it simply isn’t enough.

The United States has provided aid to Syria since 2012, according to a U.S. Government Fact Sheet, but the amount of educational aid still falls far short of what the children need, according to UNICEF’s call to the international community. UNICEF has requested $624 million from the international community to address the humanitarian crisis in Syria and surrounding countries. If other countries want to prevent children from falling prey to the lure of radical groups, international donors should intensify focus on expanding learning opportunities in Syria. Currently, the U.S. government is spending $68,000 an hour to fly warplanes to battle ISIS. Meanwhile, the United Nations has received just $908 million out of the $2.89 billion needed to aid those displaced in Syria, according to Yacoub El Hillo, the top U.N. humanitarian official in Syria, in an interview with the New York Times.

UNICEF’s No Lost Generation initiative creates school clubs in places like the Safi Al-Din Al-Hilli School in Qamishli where children can go to make up missed classes, and UNRWA and other partners have created a self-learning curriculum that corresponds with the national system. These programs are still struggling to catch up with the surging need.

Policy makers, donors and the international community at large need to redirect their attention to Syrian children’s education. The national education system needs further support to maintain safe environments, and the nation needs to make teachers, supplies and self-learning packages more widely available.

The Syrian government, which is working toward collaborating with rebels to end the conflict, simply does not have the resources to focus on the education crisis.

Even the most vulnerable child should have the opportunity to learn.

Nearly half of all Syrian schoolchildren have dropped out of school in the past three years. It’s all too possible that these children will grow up lost and traumatized, and look for support in the wrong places.

If we want to prevent children from adopting radical mentalities, we need to keep them in class and out of radical environments.

Write to Mariam at [email protected].