I’m used to pessimistic old conservatives, but something my uncle said a year ago probably takes the cake as the bleakest view.

“Our generation had it made. But you guys” — meaning me and my cousins — “better be prepared for smaller homes and a lot less,” he said. “The American Dream is dead for you.”

Honestly, the dream’s death doesn’t bother me much. To quote Billy Joel — the American singer, raised, like me, in the suburbs of New York — “Who needs a house out in Hackensack? Is that all you get for your money?”

But as much as I usually ignore my elders’ negativity, my uncle raised a good point. Millennials have a lot of questions hanging ahead of them, and where we are going to live is the biggest. American cities lack affordable housing.

The American Dream has always been tied up in the idea of home ownership — a husband and wife, a son and daughter, a dog and cat, standing outside their suburban home with a white picket fence.

American governmental policy has reflected the push for brick and mortar for most of its history. The Homestead Act of 1862 granted any American a plot of land in the west who was willing to improve on it — read, build a home and farm on it. In the 20th century, the federal government created the Federal National Mortgage Association and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation — Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, respectively — to inject more money into the mortgage market and expand home ownership.

Like many Pitt students, I grew up in rows of endless cookie cutter houses in suburbia. Just think of how many times you heard, “I’m from outside Philadelphia,” during your first awkward attempts at making friends as a freshman.

In fact, according to Pitt’s 2015 Factbook for all Pitt campuses, if we subtract students from Philadelphia and Allegheny county as being of an “urban” origin — which is a big assumption — 62 percent of the 24,098 students from Pennsylvania are from suburbs or rural spaces. Such in-depth numbers don’t exist for out of state students, but I don’t think they would make much of a difference.

I can’t speak for all of my fellow students, but I do know one thing. My two story brick house gave me a fine upbringing, but I don’t plan on going back anytime soon. For all of us soon-to-be adults at Pitt, finding a place to live will be tough. Even if we wanted to move back to the suburbs, buying a home on a starting salary is out of the question. And lending for homes is understandably tight, as it’s on the heels of a financial collapse caused by bad mortgages.

The outlook for staying in the cities and renting doesn’t look good either. According to a study from Harvard University, home ownership has gone down from 69 percent in 2004 to 63.7 percent now.

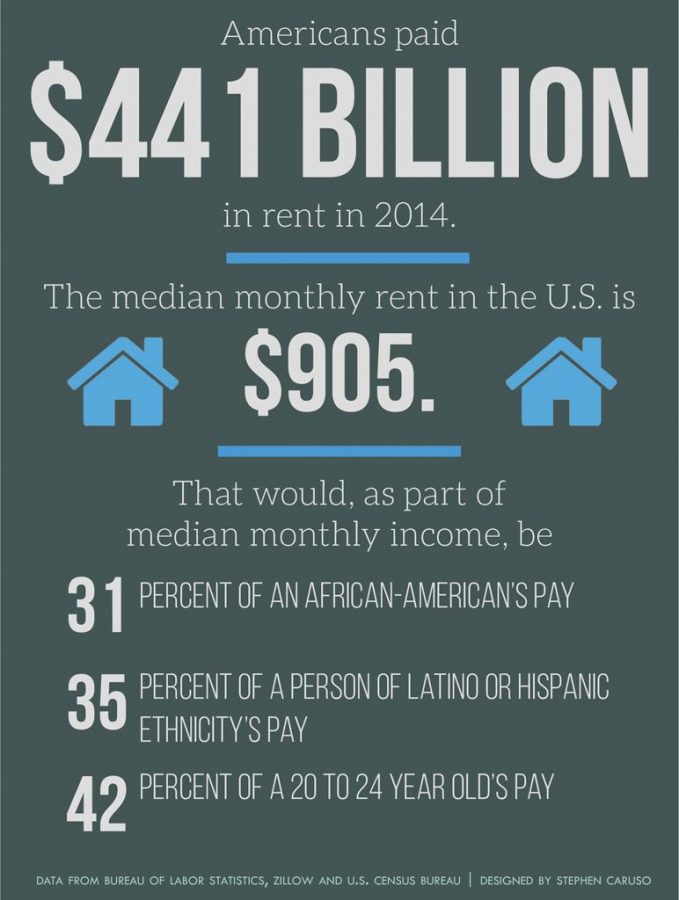

In response, the demand — and price — for renting has gone up. According to Zillow, an online real estate database, Americans paid $441 billion in rent in 2014, a $21 billion increase from 2013. Zillow also reported that since 2000, rent has increased at a rate double that of income.

If you managed to keep your homes, you’d be paying less taxes. The U.S. government implicitly supports home ownership by allowing the deduction of home mortgage interest from one’s income tax. For renters, no such federal deduction exists. Some states, such as Massachusetts, allow for a paid rent deduction on state income tax, but it’s usually limited to some percentage of total rent paid.

Instead, those being forced to foot that increased bill are those least able to afford it. According to the National Multifamily Housing Council, 59 percent of renters make under $35,000 a year, with a median income of $27,987.

Interestingly, the mean income of renters — $40,391 — is higher than what 59 percent of renters make. And this statistic points to the root of the problem — cities don’t have a affordale housing.

The housing environment in the United States does not support those who really need housing. According to CityLab, an offshoot of The Atlantic that focuses on urban issues, the United States loses nearly $1.6 trillion dollars every year due to the lack of affordable housing in cities with economic growth.

All of the growth in urban housing has been in high-income residential towers — such as 432 Park Ave., in New York City — or from gentrification of low income neighborhoods into yuppy centers. So while 59 percent of renters make under $35,000 a year, the mean sits at $40,391 because of renters in 1,000 foot penthouses and restored brownstones.

If you have money, you’re fine. But for the young college student or the beleaguered resident, the situation isn’t improving. According to a different study from Harvard, it was the young and black residents who had the largest decline in homeownership rates from the 2008 financial crisis.

And after being foreclosed on, individuals have to rent. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median monthly rent payment, including utilities, in the United States is $905. Comparing that to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ numbers on median pay, rent would be 31 percent of a black person’s pay and 42 percent of a 20-24 year old’s pay of all races.

And that’s not including food, transportation, health care and any other expenses bound to pop up. How is anyone supposed to save for their white-picket-fenced home if they can barely keep a roof over their head?

The solution isn’t a government takeover. Rent control will lower prices, but we need an increase in supply, not an artificial ceiling. If we decided to try and improve home ownership in the suburbs, that will only lead to too-big mortgages offered by banks “too big to fail” — or what caused the 2008 crisis.

Instead, the solution is more indirect. CityLab mentions that a lack of transit infrastructure is huge — for free markets to work properly, people need to be able to move freely. Cities need to expand bus, subway and bike lane systems to push back against “transit deserts.”

These “deserts” are areas underserved by public transportation. For example, Pittsburgh Port Authority just recently expanded its bus service into Baldwin and Groveton. Before the new routes existed, residents of Baldwin had to walk two miles to catch a bus to go Downtown.

This expansion of service will allow Downtown job seekers to live in Baldwin, taking the demand away from neighborhoods like Oakland, Shadyside and Squirrel Hill, as well as slowly decreasing prices. This is just one neighborhood, but as cities become more interconnected, this price-relieving effect will grow.

Actually creating more affordable housing is tricky. Deregulation that will cheapen the price of construction is beautiful on paper, but those regulations have a real impact in life. What will we get rid of, requirements for fire escapes?

The best move is to try and control speculation and centralized development in favor of small-scale improvements. The Homestead Act worked wonders to settle the west — could an urban version be implemented? Instead of developers, give tax breaks and small loans to individuals willing to put in the work themselves to fix their homes, whether current owners or those on the market.

We shouldn’t discourage the big developers, though. Instead, we should encourage them to develop brownfields — areas once used for industrial purposes — into new housing, and make sure transit properly connects to any newly developed areas.

Finally, end the federal home mortgage interest rate deduction, which implicitly supports mostly middle class homeowners. The federal government should set up a generic deduction for rent paid, capped at some arbitrary number. With how much rent varies by state and city, finding the ideal number will be hard, but should, ideally, mostly support low-income renters.

As development pushes up prices, residents will need a break. This will also help low-income individuals hold on to their homes in the face of gentrifying neighborhoods — the original residents catch a break, and the gentrifiers pay the full tax.

By doing this, we can make cities more affordable, and after some scrimping and saving in your small apartment, you could afford that white-picket-fenced home — if you want.

If we don’t act, that choice — and the American Dream — is as good as dead.

Stephen Caruso is a senior columnist who writes on economic and social issues for The Pitt News. He is also the production manager. Email him at [email protected].