We’ve locked away precious pieces and depictions of our humanity in our rush to commodify society and — ironically— cling to our wealth.

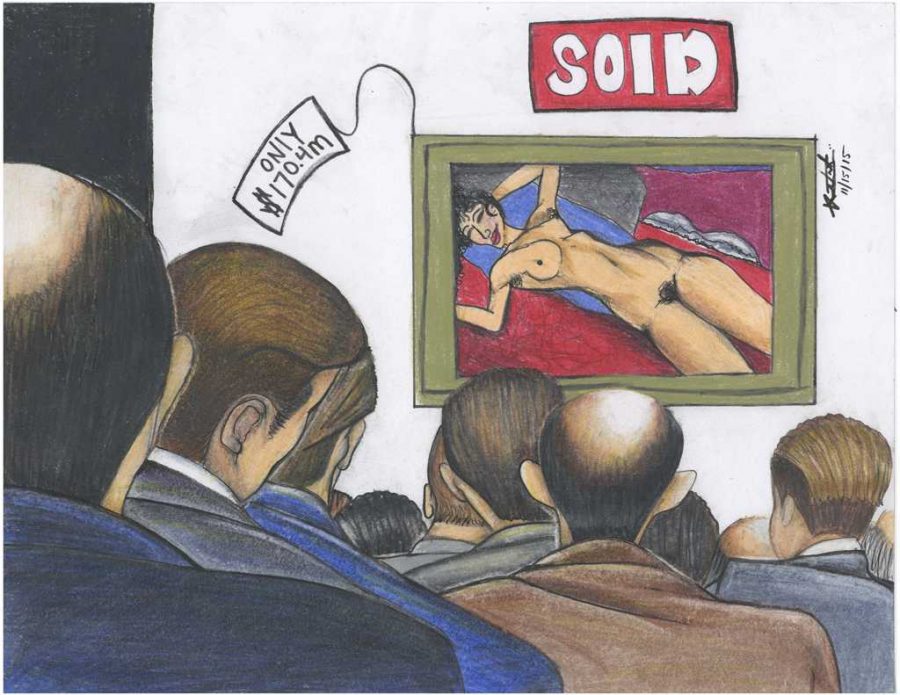

Last Monday, New York’s prestigious Christie’s Auction House sold a painting by Italian modernist painter and Picasso contemporary Amedeo Modigliani at auction for an incredible $170.4 million to chinese billionaire and amateur art collector Liu Yiqian.

Some, including the Guardian’s art critic Jonathan Jones, questioned whether the painting — masterpiece or not — was really worth its huge price tag. In an opinion piece for the Telegraph, arts editor Sarah Crompton envisions the third-world children we could feed using the millions spent on paintings like Modigliani’s 1918 masterpiece “Nu Couché.”

Critics are right that prices in the art market are outrageous, but this is not because we overvalue paintings. If anything, we underprice paintings selling for nine figures to undeserving buyers — art is a public good that today’s art market treats as a private commodity.

For all the claims that the modern art movement developed as a way for lazy artists to strike rich with minimal effort, astronomical prices are a fairly recent development.

Every one of the top-10 most expensive paintings of all time sold within the last 10 years, including the $300 million sale of Gauguin’s “Nafea Faa Ipoipo” in February. The art industry now values art advisers for their sharp business acumen in the pursuit of pricey art objects, and not solely for their art knowledge. According to the Bureau of Labor, the median salary in 2012 for an art director was $80,880. In 2014, the median salary had grown to $97,850, according to the Bureau of Labor.

Auction houses sometimes get the blame for manipulating modern and contemporary art markets to maintain the illusion of strength and stability. Sergey Skaterschikov, the founder of Skate’s Art Market Research in New York, called big-name auctions, such as like the auction where “Nu Couché” sold, “too big to fail” in an article for Bloomberg Business.

Art houses use invaluable works of art as collateral for housing enormously risky bets in lesser known artwork. The necessity to keep up large profit margins easily eclipses concern for the art itself.

Although Liu, who wanted to add more Western pieces to his collection of mostly Chinese antiquities, seems to have an aesthetic interest in Modigliani’s painting, oftentime the fine art market serves as a safe haven for the super rich to isolate their money from governments’ reach.

Spanish aristocrat and art dealer Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza, accumulated a private art collection that resides in a museum owned by Spain in the remote Cook Islands. Emails obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists showed that Thyssen-Bornemisza owned two offshore companies — Nautilus Trustees Limited and Sargasso Trustees Limited — in tax havens that purchased valuable artwork, saving her from possibly millions of dollars a year in taxes.

The aesthetics of modernism or any individual artwork has little to do with the art price boom.

What’s more, artists who are supposedly making a fortune off scribbles on a canvas turn out to have no such financial incentive.

German postmodernist painter Gerhard Richter has repeatedly broken the record for highest auction price for artwork by any living artist. While his “Abstraktes Bild” sold at auction in February for the equivalent of around $43.7 million, Richter earned slightly over the equivalent of $8,000.

“We artists get next to nothing from such an auction. Except for a small morsel, all the profit goes to the seller,” Richter said in a March interview for the Guardian.

Richter also lamented the negative impact of astronomical prices on “‘serious galleries and young artists.” Due to the rise of notably high-stake art fairs, London’s commercial galleries feel considerable pressure. Today’s art market stifles new young artists’ creativity by forcing them to be entrepreneurs as well as creators.

The market solution for the art “industry” — if we could call it that— evidently is not beneficial for art itself. Private purchase of masterworks almost guarantees that the buyers will hide them in a private gallery or a safe. Worse, as the Guardian’s Crompton suggests, absurdly high prices “make people think that art is out of their reach, something that is not for them.”

The record holder for most expensive painting to sell at auction is Pablo Picasso’s “Les Femmes d’Alger,” selling at the price of $179 million in May. This painting — roughly the same period, style and pricing of Modigliani’s “Nu couché” — is currently residing in a private, unmapped vault. No one except the owner may see it, and no one except the owner knows where it is.

It’s unseemly for a Picasso to go unseen and unadmired. It’s a misfortune that the painting isn’t hanging in a public gallery or museum, and it’s a misfortune that we must address.

Crompton agrees that “a civilized society needs art as well as bread,” and we must protect a resource of that importance. Government funding for the arts should help protect and retain important paintings like a Picasso masterpiece.

Otherwise, millionaires just might lock up our humanity with their treasures.

Henry primarily writes on government and domestic policy for The Pitt News.

Write Henry at [email protected].