Weight loss surgeries don’t cure obesity, but according to research from Pitt’s Graduate School of Public Health, they might contribute to a healthier lifestyle.

Researchers at the School of Public Health spent three years monitoring 2,221 morbidly obese patients who underwent bariatric surgeries to restrict the amount of food their stomachs could hold. The study concluded that a majority of the patients experienced less joint pain and had an easier time walking.

Wendy King, lead researcher and associate professor in the epidemiology department at Pitt, and her team presented the results of the study in Los Angeles at the Nov. 2-6, ObesityWeek, the annual international conference of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and The Obesity Society. The National Institutes of Health funded the study.

“This was the first study following modern day [bariatric surgery] procedures,” King said. “It’s the first with such a big group, such long-term follow-up and actually looking at predictors of change and factors related to change.”

Some patients did not experience as much improvement after the surgery. Pre-existing medical conditions, old age, lower income and depressive symptoms had a negative impact on a patient’s improvement after the surgery.

“Our hope is that these data will help patients and clinicians develop realistic expectations regarding the impact of bariatric surgery on these aspects of their lives,” King said in a release.

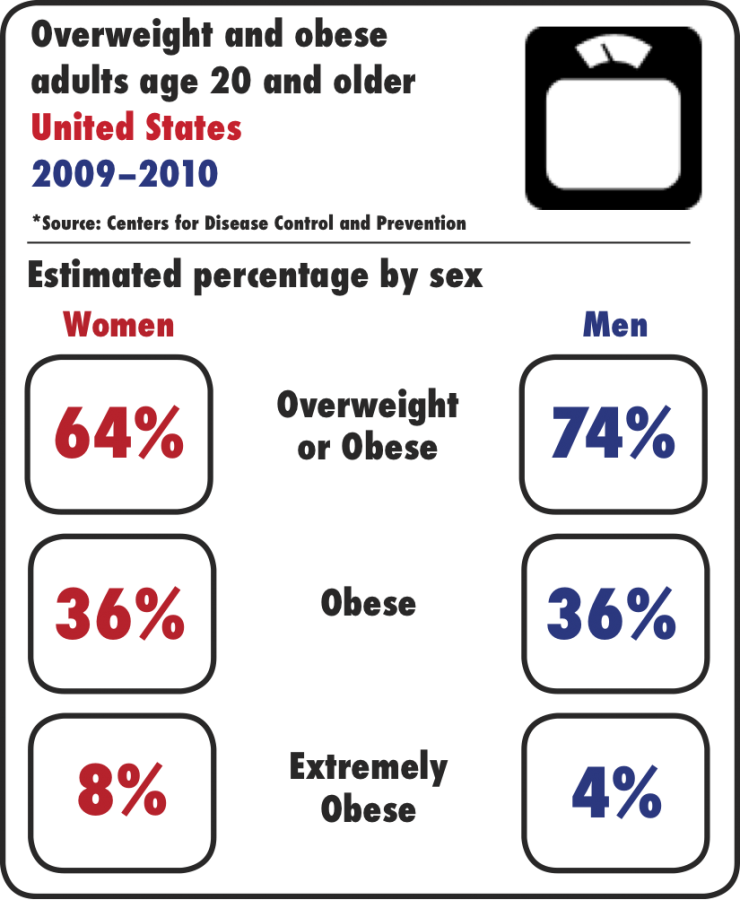

Since the 1980s, the percent of people in the United States who are morbidly obese — with a BMI greater than 40, or greater than 35 with a serious health problem — has more than doubled. More than 6 percent of people 20 and older in the United States were morbidly obese from 2011 to 2012, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Between 2011 and 2013, the number of bariatric surgeries on extremely obese patients has also gone up 15 percent, according to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Meg Mayer-Costa, a dietitian in Pitt’s Student Health Center, said bariatric surgery does not fix obesity, but is instead a tool for improving a person’s overall health.

“For many people, learning to use food properly as nourishment was a new prospect,” Mayer-Costa said. “With bariatric surgery there are limitations to a person’s intake, so every sip and bite has to provide quality nutrition.”

The researchers only focused on patients who had BMIs over 35, David Flum, a co-researcher at the University of Washington, said. Those people who lost more weight and began a healthy routine before the surgery experienced more positive effects afterward.

“This may be because exercise behaviors are made more routine and support a healthy lifestyle afterward,” Flum said, “or that the recovery in the days and weeks after surgery is made easier with a better level of fitness.”

The study found “50 to 70 percent of adults with severe obesity who underwent bariatric surgery reported clinically important improvements in bodily pain [and] physical function,” according to the release.

Additionally, the study revealed that more than half of participants who had a mobility deficit prior to the surgery did not after surgery.

“We [found] that the more heavy you were before surgery, the more likelihood you were to have walking limitations,” Flum said. “Not all people with walking limitations got better after surgery, and we think those who lost more weight and had less structural problems did best.”

Structural problems, according to Flum, include severe bone and joint problems that might have led to the need for a wheelchair before surgery.

While King said the surgeries were helpful in alleviating certain stressors, in the long term, patients should seek weight loss the old-fashioned way.

“Adhering to a more strict diet that’s healthier, [eating] less food and increasing activity level are important parts in the overall success of the surgery,” King said.