To craft functional foreign policy, we need to have a basic appreciation of the world outside the United States.

Can someone let retired neurosurgeon and 2016 Republican presidential contender Ben Carson know about this requirement?

Carson committed a series of foreign policy gaffes that exposed a severely limited understanding of international realities. At the Nov. 10, GOP primary debate, Carson claimed, “Chinese are there,” in reference to Syria, despite the White House officials and the Chinese government saying otherwise. In a radio interview in March with conservative commentator Hugh Hewitt, Carson also couldn’t recognize the three former-Soviet Baltic states as members of NATO.

Carson’s fumbles aren’t an individual shortcoming— they stem from a culture of geographic neglect. Americans have a long-standing reputation for being oblivious to the world outside their own borders.

But this dearth of geographical knowledge isn’t just embarrassing, it hinders how the United States interacts with foreign nations.

Political outsiders like Carson do not possess extensive formal training on foreign relations — if an outsider wins the upcoming presidential election, their limited geographic knowledge will color foreign policy negotiations. In a political climate where international relations lead, we need education focused on the interconectivity of the world. But this goes beyond being able to identify a country on a map.

It’s understandable that a retired neurosurgeon might not know the international landscape as a career politician. But when that candidate currently has 18.8 percent of Republicans’ support in national polls, according to Real Clear Politics, the lack of concern for geographic literacy becomes a threat to effective foreign policy.

Geographic illiteracy in the general population supports rash foreign policy decisions from our political elite — people are more easily swayed when they have limited knowledge on the subject.

In April 2013, Pew Research Center found that 45 percent of Americans that were surveyed supported United States-led intervention in the growing conflict in Syria, despite only 18 percent of all respondents claiming to follow news from the country “very closely.”

Ignorance about the rest of the world isn’t limited to the Middle East, either. The 2014 Ebola outbreak was limited largely to Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and a few other West African nations. Nevertheless, tourism in countries thousands of miles removed, like Kenya and South Africa, suffered significantly lower numbers of visitors because of lingering fear after the outbreak, according to Heidi Vogt of the Wall Street Journal.

Federal education policy sustains this disregard for geographic literary in politics.

According to Penn State professor Roger Downs, curriculums increasingly heavy in math and reading can result in low levels of proficiency in geography.

Downs released a statement with the U.S. Department of Education’s 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress Report Card, stating that as “classroom time becomes an even more precious and scarce commodity, geography, with subjects such as history and the arts, is losing out in the zero-sum game that results from high-stakes testing.”

This loss is already beginning to show festering results.

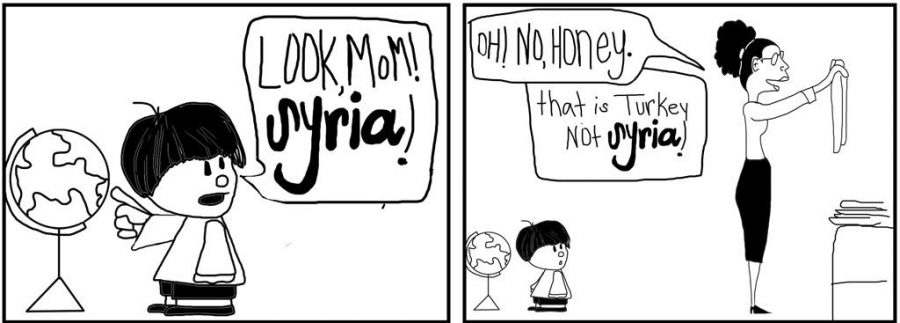

A 2013 Pew Research Center survey asked subjects to identify a shaded country on a map of the Middle East. Only half of the respondents correctly identified the country as Syria. Almost 20 percent of the respondents identified it as Turkey — the United States ally, NATO member and EU applicant to Syria’s north — while another 15 percent had no answer.

The survey also found that younger people scored lower than older people on tests of political knowledge. Only 46 percent of those younger than 30 correctly identified John Kerry as a nominee for secretary of state. Younger people were also less likely to identify Chris Christie, governor of New Jersey, and John Boehner, who was then serving as speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Solving the problem of low geographic literacy will be more complex and yield greater benefits than simply teaching Americans where to point to on a map, but it still starts by teaching Americans to be spatially aware of the world around them.

Not everyone is going to wind up forging foreign relations deals, but geographic literacy will beam a spotlight on everyone’s political and cultural awareness.

Henry primarily writes on government and domestic policy for The Pitt News.

Write Henry at [email protected].