When Murray “Buzz” Susser enrolled in Pitt’s School of Medicine in 1962, he hoped to someday be the first doctor on the moon.

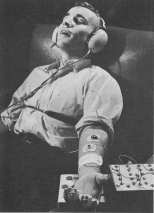

An Air Force Reserve captain and former National Guard pilot, Susser wanted to trade jets for spaceships as a medical astronaut on Project Apollo. He was ready for the gig too — Susser took polygraph tests to see how he responded to stress and learned about a device that supposedly could detect alien life. But there was one problem.

“My wife wasn’t really keen on my being an astronaut,” Susser said. After he asked his wife what she thought about his ideas, she quipped, “You don’t love me.”

Susser, who now has his own practice specializing in alternative medicine, wasn’t the only one at Pitt with a penchant for the cosmos. After President John F. Kennedy’s “We choose to go to the moon” speech in 1962, Pitt launched into the Space Age — proposing a full-blown space research center, researching lunar samples and even hosting James Webb, the administrator of NASA, to speak to Pitt students at 1963’s commencement ceremony. We talked to Zach Brodt, an archivist at Pitt’s Archives Service Center to get the highlights from space-related happenings at Pitt in the ‘60s.

be the first doctor on the moon. Photo courtesy of Historic Pittsburgh

Sandwiched between the “We choose to go to the moon” speech and the Cuban Missile Crisis, there’s little record of JFK’s visit to Pitt in October 1962. Even though he didn’t mention NASA’s space program — instead, the stop was part of a campaign for the Pennsylvania Democrats — the Fitzgerald Field House was packed with hundreds of people. According to Matthew Nesvisky, The Pitt News editor-in-chief at the time, even the basement overflowed with people who could hear JFK talk, but could not see him. “But then to the delight of the basement people, after his speech JFK came down and greeted the subterranean crowd,” he said. “I remember thinking that his hair looked the color of peanut brittle and probably — to my regret — used that in an article.”

The same year as JFK’s visit, Pitt applied for a NASA grant for what would later become the Space Research Coordination Center. The proposal called for a major space-focused research hub, which would encourage studies not only in the natural sciences, but engineering, health and social sciences as well. Pitt received $1.5 million in return from NASA and a $34 million commitment from state and private foundations the following year that went to building what is now the Space Research Coordination Center. “The emphasis on space research has also had a lasting impact on Pitt, such as the 1963 decision to rename the Department of Geology the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences to reflect the expanding scope of their work,” said University archivist Zach Brodt, who added that Pitt aimed to focus more on cosmic research and less on producing hardware for future missions.

Shortly after Pitt announced the construction of the Space Research Coordination Center, Webb spoke to Pitt graduates at 1963’s commencement ceremony. Just as JFK’s words aimed to ignite the American public’s quest to put a man on the moon, Webb’s address urged the freshly graduated students to join in the innovation that would come over the next decade. Parting with the crowd, Webb said, “That is your opportunity, if you grasp it, in this exciting age, you can help to write your own parts in the drama of creation.” A year later, Henry Hillman broke ground with other NASA and Pitt leaders for the Space Research Coordination Center, which opened the following year.

After the Lunar Orbiter 1 spacecraft gave us our first glimpse of the moon in 1966, NASA shipped out the photographs it gathered to scientists around the country, hoping to point out spots where the Apollo missions could land. Nasa selected Pitt geology and planetary science professor Bruce Hapke to analyze the pictures, and was later one of about 100 chosen to study the lunar samples brought back by Apollo 11. His work sought to answer why the moon is so dark, analyze the effect of solar wind on lunar soil and understand the effects of weightlessness on the body. Still at Pitt, Hapke is recognized as a critical figure in space research — he even has a mineral named after him, Hapkeite.

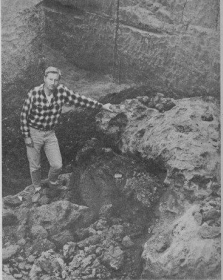

During his eighth summer in South America, Pitt geology professor William Cassidy dug up an 18-ton meteorite — making it the sixth largest recorded by 1969. Found at Campo del Cielo, Argentina, Cassidy’s finding outweighed the 4.5-ton “El Toba,” the largest meteorite found by the area’s early settlers. Cassidy told the Alumni Times, “I had thought at the time it would be strictly a one-summer project, but when we got there we found three new craters and discovered that in some areas we couldn’t search for more than a few seconds with the surplus Army mine detectors without finding a new meteorite.”

18-ton meteorite. Photo courtesy of Historic Pittsburgh

As the decade closed, Pitt celebrated the Space Research Coordination Center’s interdisciplinary, less mission-oriented approach to space research — a rarity at the time. During the ‘60s, 114 research reports came out of Pitt’s space program — examining everything from studies on atomic hydrogen to early investigations of Mars’ atmosphere. Today, the institution is more concerned with geology and planetary science, according to David Turnshek, an astronomy professor at Pitt. He said, “Back when Bruce Hapke, now emeritus professor, was on their faculty, they really were still doing space research, but since then their focus has shifted to geology and planetary science, including geology and volcanology on Mars by Michael Ramsey — which is perhaps one last connection to planetary science.”