As I drove home listening to NPR last week, I heard that a group of white protesters had seized a federal wildlife reserve in Oregon from what they feel is a tyrannical government. The group was heavily armed.

I bit my lip, concerned. Then, the broadcaster called the group a “militia.”

Cue the déjà vu, the routine annoyance and the knee-jerk reaction in my head asking the broadcaster to “just call them terrorists.”

I had the same initial reaction in June 2015, when Dylann Roof, a young, white man, killed nine innocent churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina. According to the U.S. Code, he had committed domestic terrorism. He had “endangered human life in violation of federal or state law.” But instead of labeling Roof a terrorist, media outlets began speculating whether he was mentally ill.

Many people began to demand that the media “call it what it is: terrorism,” and others began doing so on social media. We are seeing it play out again, and I’ve realized that my hot-headed solution ignored a core problem.

Here’s the issue: the word “terrorism” carries a lot of baggage.

While the demand to equalize the use of the word “terrorist” is well-intentioned and seems logical at first, it’s flawed and potentially detrimental. This rhetoric has had very real, and sometimes deadly, consequences on innocent Muslim, Middle Eastern and South Asian communities in the United States and worldwide.

The seriousness of the media’s double standard shouldn’t lead us to equalize the use of this oppressive language. Rather than expanding its use, we should end our reliance on it.

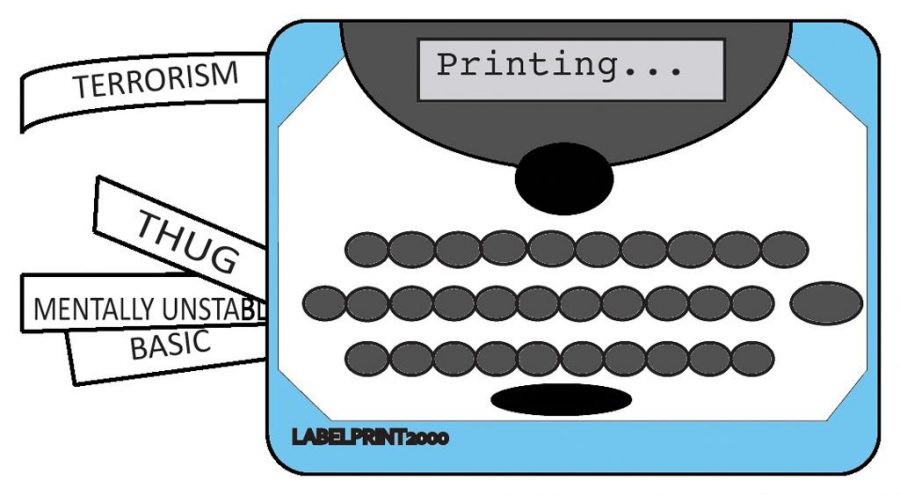

Since 9/11, and the onset of our country’s War on Terror security movement, we have begun to use “terrorism” to describe any violent acts specifically committed by people with brown skin or Muslim-sounding names. The image of a Muslim terrorist is now a stereotype with negative consequences. Muslim American and other minority children flinch at the word “terrorist,” in fear of bullying or discrimination, and not without basis.

Words like “terrorist” and “jihadi” expanded beyond the scope of the government’s initiative during the War on Terror and now dominate the media with any criminal with a similar profile. The subsequent increase in stereotyping and discrimination makes it seem unwise to rally around the words that pushed them forward.

According to an article from ABC News, U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch expressed concern that paranoid rhetoric was inciting hate crimes. FBI data shows that there has been an average of 12.6 suspected hate crimes against Muslims in the United States every month.

The United States has harmed countless innocent people in Iraq and Afghanistan in the name of fighting “terrorism.” Civilians become collateral damage. Blameless individuals are arrested around the world, like Shaker Aamer, a British resident who was detained in Guantanamo Bay for 13 years without charge. Prisoners like Aamer face years in prison conditions that are illegal on American soil.

Regardless of whether or not the government technically views the Oregon occupation as a terrorist threat, we shouldn’t be quick to label them as such. It’s unhelpful to try to reduce the bias surrounding the word “terrorist” by making the term a common label for anyone who commits an act of potential violence.

We want to eliminate America’s preoccupation with terrorist threats to national security and reduce racial and religious profiling. We want our media to instead occupy itself with national security in general.

The threat of terrorism exists, but our 15-year obsession with terrorism has produced vile actions that have killed innocent people and impacted minority lives in America. To restore civility, we should avoid using the terms that made our preoccupation with terrorist threats common in the first place.

Calling people “terrorists” should not be our automatic reaction — regardless of who the subject is and regardless of whether the label is technically accurate. When it comes to reporting violence and violence-related events, our media should use less — not more — stereotypical words that imply serious crimes, and instead use more objective-writing tactics for reports and news headlines.

To get there, everyday citizens should fight against harsh media bias, but not by encouraging an increase in terminology that has historically created suffering for others — no matter how immediately useful it may seem.

Mariam Shalaby primarily writes on social change and foreign culture for The Pitt News.

Write to her at [email protected]