The future of the American worker is in jeopardy.

If you talk to the average college student today about their post-graduation plans, you’ll probably detect a note of anxiety and uncertainty.

This emotion was expected and commonplace several years ago in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Today, though, with the unemployment rate hovering at a normally respectable 5 percent — the lowest in eight years — according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, one would expect more optimism.

Nonetheless, this anxiety persists because the U.S. economy is still struggling, and relief is nowhere in sight for the American worker.

This anxiety isn’t limited to college students. According to Gallup’s economic confidence index — an average rate of Americans’ feelings about the economy — American confidence in the U.S. economy is a disappointing negative-12 for the week ending Jan. 24.

Frustratingly, this lack of confidence has been par for the course since the start of 2015. Confidence had actually been in positive territory for much of January and February, but it didn’t last.

To understand Americans’ pessimism, we have to unpack some of these figures.

When we hear about 5 percent unemployment, we are hearing what is called the U-3 unemployment rate. This is a basic measure of how many Americans in the labor force are currently employed. Problematically, this number ignores several key measures in unemployment.

For example, if an individual gives up looking for work, they are no longer considered a part of the labor force and are then not considered officially unemployed. Additionally, this measure does not account for those who are only employed part-time because they cannot find full-time employment.

When we factor these in, this more representative measure, called the U-6, showed an unemployment rate of 9.9 percent in December.

One way to better understand this number is to study the labor participation rate, a simple measure of the percentage of Americans over the age of 16 who are in the work force.

At the start of the Great Recession in 2008, the labor participation rate was steady at about 66 percent for several years, according to the BLS. Today, the number stands at 62.6 percent, the lowest participation rate in 38 years.

Gradual retirement of the baby boomers does account for some of this decline, but it is no coincidence that the decline began with the recession and has only recently ceased.

This decline in labor participation isn’t supposed to happen during periods of economic growth, especially after a recession. According to a recent report on this phenomenon from Express Employment Professionals, an association that aids job seekers, a decline in unemployment should correspond with growth or, at the very least, stabilization of labor force participation.

This is demonstrative of a phenomenon that has been visible since the start of the recession. The job market is discouraging more and more young Americans who then give up and go home to live with parents, as evidenced by recent Pew Research analysis of U.S. Census data.

The country’s current economic malaise is also present in employed American’s incomes.

Since the start of the recovery, wage growth is much slower than expected in a normal recovery. In December, hourly wages grew only one cent from the previous month, closing out a 2.5 percent rise in inflation-adjusted wages from the previous year. For comparison, that rate reached 3.8 percent in mid-2007 before the start of the recession.

The problem is, if unemployment was as low as we hear, we would see far more robust wage growth.

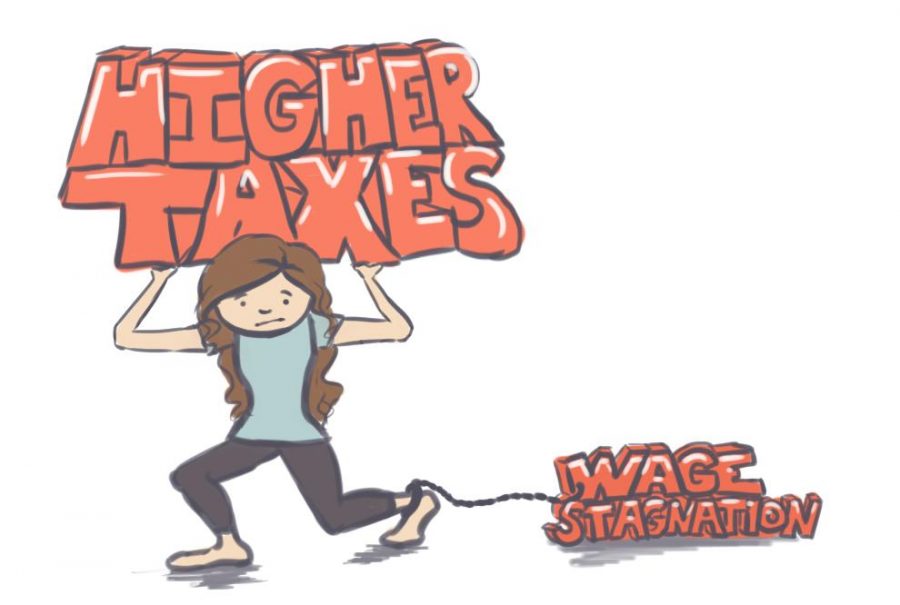

As The Economist explains, when unemployment is low, companies fight to retain workers . This causes businesses to driveup wages. This has not been the case in the aftermath of the recession, though. Wages have been stagnant for the last five years.

For explanation, look at the labor participation rate. Low unemployment hasn’t positively impacted wages because unemployment actually remains too high.

But why has recovery dragged?

The problem lies with feckless government handling of the economy, particularly in the last seven years. The Affordable Care Act is a prime example of this counterproductive meddling with our economy

The ACA forces all businesses with 50 or more employees to either provide health insurance or pay a penalty. To avoid having to provide health insurance or pay the penalty, many businesses instead move employees from full-time to part-time work and pass on costs to the consumer. Everyone hurts in this cycle.

Another classic example of the federal government’s economic mismanagement is the chronic overregulation of the private sector.

According to the Government Accountability Office, federal regulators added 2,400 new regulations in 2014. The Obama administration also issued 184 major regulations between 2009 and 2014 at a cost of $80 billion to the private sector, according to analysis from the Heritage Foundation. Examples include green-energy mandates on walk-in coolers and freezers and mandating rearview cameras in new cars at estimated costs of $485 million and $583 million, respectively.

And, of course, there are always taxes.

Today, the combined federal and state corporate tax rate can reach as high as 39 percent. This makes the U.S. corporate tax rate the highest of all the countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, which includes Australia, Japan, Mexico and all of Western Europe.

Is it any wonder that so many American corporations are moving their jobs and headquarters overseas to dodge tax rates? While most students aren’t aiming for jobs in manufacturing, they are a vital plan B for the growing number of them who can’t find jobs in their fields. With companies like Nabisco, Ford and General Electric moving jobs and assets out of America, doors of opportunity are closing for future generations.

Just last week, the Bureau of Economic Analysis revealed that U.S. GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2015 was an anemic 0.7 percent. This is just one more disappointing indicator in what seems to be a very disappointing economy.

With unemployment still high, labor participation declining and economic growth stagnating seven years after the recession, the outlook for young Americans continues to look grim.

If the United States is to once again provide the opportunity or prosperity it once did, we must take power back from bloated federal bureaucracies and return it to the people in the private sector who drive our economy and create opportunity.

Write to Arnaud at [email protected]