Skimming over the syllabus in my gender studies class, I noticed something new amid the usual blocks of deadlines and grading policies — a paragraph on gender-neutral pronouns.

I was happily surprised to see the emphasis on gender-neutral pronouns, which are often they/them/theirs pronouns, especially in light of criticism that attempts to invalidate these pronouns by claiming that they are grammatically incorrect.

Syllabi inclusion is an important step, but it should only be a start to make our campus more welcoming to students of all gender identities.

Since kindergarten, schools instill us with a reverence for the English language. From slow, deliberate cursive writing to countless “Schoolhouse Rock” videos, we learn to value and unconditionally respect the rules of language.

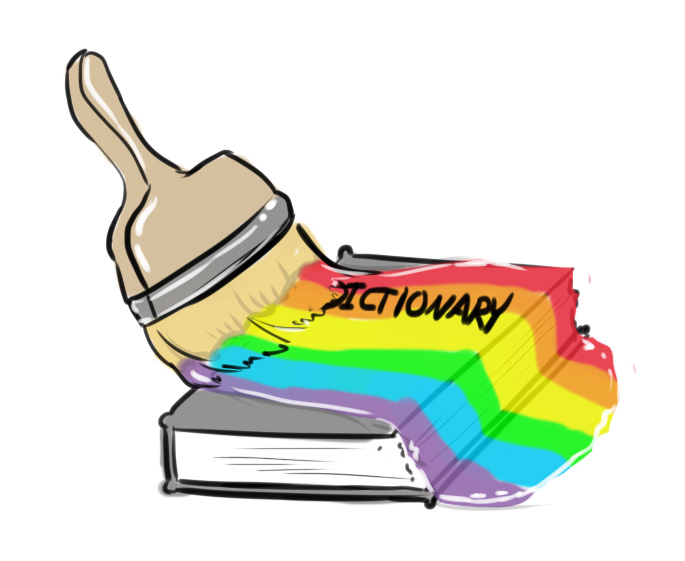

But a culture of blind obedience for traditional language rules does more harm than good, as it polices and shames those who do not conform to the gender binary: she or he. This shaming overlooks the long history of the singular “they” within English language and literature, present in works by renowned authors that range from Geoffrey Chaucer to C.S. Lewis.

People ignore this detail because they don’t really care about the English language rules — they only care about societal regulations and get stuck on the predominant use of “they” for a plural subject.

These critics and I could agree on one point, though, if they were honest about their hangups — the grammatical rules of the English language are of little to no consequence in society.

Our language has changed and evolved throughout time — try to find me a speaker fluent in English that can read Olde English, which dates back to fifth century Germanic tribes and bares minimal resemblance to our language today.

I am continually in awe of the vocabulary differences within my own home. I’ve never met anyone other than my dad who calls a couch a davenport, and he’s still grappling with the idea of a selfie.

We continue to constantly create new nouns, verbs and phrases to meet society’s needs and ease the growing pains of communication. Our language is not a set, archaic algorithm with only so many outcomes — it continues to change so long as its speakers do.

Language should not be something that limits our gender expression, but dismantles the restrictive gender binary, a malleable social construct.

In nearly all tenets of society, from childhood books to college dorms and public restrooms, we grow up learning that there are only two gender options — man and woman — and attach stereotypes as so.

People who identify as non-binary have been around for a long, long time — across the globe and throughout history, there have been people who do not identify exclusively with one gender or another.

For example, the creation myth of the Mohave tribe — located on the West coast — has terms for four genders, and Navajo culture recognizes and reveres nadleehi, or people who are neither just man or woman.

Those who are non-binary are not making a political statement or trying to destroy gender binary from the inside out — they are people trying to live as they truly are in a world that constantly tells them that they are wrong.

Right now, we meet someone and automatically refer to them as either she or he. But it is time to consider “they” as an option during our first introductions, and support those who use this pronoun without petty grammatical reproach.

Pitt’s Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Program made strides by including guidelines regarding gender-neutral pronouns in their syllabi, which pulls from an in-depth document of gender inclusive and non-sexist guidelines and resources.

Todd Reeser, program director of the GSWS department, hopes these inclusions will allow GSWS to lead by example so that “departments across campus will comes to us as they think about how to incorporate gender-inclusivity into student writing and into the classroom.”

itt’s recent addition of gender-neutral housing is a great first step, as was the addition of the preferred name option.

While it is important the GSWS department has set a standard for other departments to live up to, we need to take greater steps toward making Pitt a more gender-inclusive school.

Gender-inclusive guidelines should appear in every syllabus. A policy regarding gender inclusivity should not be limited to just the GSWS program, but mandated in all departments. Pitt should give its faculty, students and workers an opportunity to indicate their gender pronouns across all fronts — from job and college applications to classroom introductions.

University spokesperson John Fedele said that while there are currently no plans to require that Pitt faculty include name preference information in their syllabi, Pitt is committed to gender inclusivity.

“The Provost’s Office was instrumental in working with the Registrar’s Office to create the preferred name option and will continue to work towards creating an open and inclusive environment for all members of the Pitt community,” Fedele said.

Pitt’s preferred name option allows students to use a name different than their legal birth name in “the course of University business and education.” It’s an important administrative provision, but it’s time to move this acceptance into the classroom.

Our society imposes an invisible line in the sand when it comes to gender expression, which our language’s two predominant pronouns only fortify. These limited options condition us to constantly wonder whether someone is “a man or woman,” so we know how to refer to them.

Instead of allowing the English language to limit us, we must recognize our ability to change it. Our conception of English is in our minds, not our textbooks.

We write the rules that govern our interactions, and it is time we replace archaic conceptions with pronouns that provide linguistic justice for all.

Don’t let past generations dictate the conversation.

Alyssa primarily writes on social justice and political issues for The Pitt News.

Write to her at [email protected].