Ghost Signs Haunt Pittsburgh’s Skyline

March 26, 2014

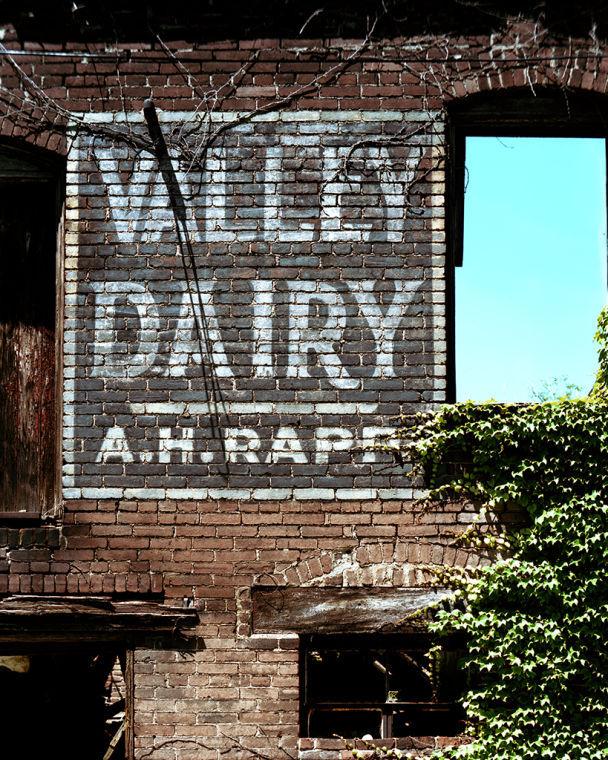

On an old brick building along Decatur Street in Pittsburgh, a faded black and white Valley Dairy”sign remains on the cracked red brick. The sign is still legible, but worn. Vines have begun to creep over the paint and the decrepit structure, leaving an incomplete, obtrusive and even ghostly image.

While some people might see the leftover signs as blights, or evidence of a decaying city, two artists have found the beauty in each sign they capture on camera.

“Palimpsests: Ghost Signs of Pittsburgh,” an exhibit running through May 16 at Pittsburgh Filmmakers on Melwood Avenue in Oakland, showcases these old advertisements and murals. Palimpsests, defined as something that has been scraped or washed away for reusable purposes, is an appropriate name for a subject such as the painted ghost signs. In the early 20th century these signs were a popular form of advertisement for everyday products from companies such as Gold Medal Flour and Wolfe Publishing.

By the 1960s and ‘70s, this form of advertising was obsolete, replaced by stand-alone billboards, and the remaining signs were either worn down by nature or entirely covered. Since then, they’ve become puzzles, revealing the red brick beneath them and leaving a discolored image that is almost impossible to discern. These eerie advertisements are distinct reminders of what Pittsburgh used to be. Faded signs for dated products such as “home-dressed meats” or “nicotine-neutralized tobacco” give us a small glimpse of daily life in the Pittsburgh of old.

Pittsburgh Filmmakers’ Kelly Bogel and Will Zavala developed the exhibit. While Zavala masterminded the project in early 2012, it was Bogel’s expertise in photography that brought his plans to life.

The exhibit features 30 large prints of nearly 180 beautifully captured images, on-screen photographs from all 150 locations where the ghost signs were found, an animation showing how the advertisements were created in the early 20th century and a map that marks the location of every sign.

“It was one of the things I noticed when I moved here,” Zavala said.

Originally from San Francisco, where painted advertisements are not as common, Zavala noticed the abundance of them in Pittsburgh when he moved to the city in 2003.

“For quite a few years I thought they’d make a good subject for a photo essay,” he said.

But Zavala encountered one major problem with the idea: The discolored signs were beginning to vanish. As the city continues to reinvent itself, these signs have been painted over, washed away or have come down with the defunct building they were painted on.

“I remember noticing one on North Negley [Avenue], and when I tried to show a friend, it wasn’t there,” Zavala said.

In order to make the project a reality, Zavala knew that it needed to start as soon as possible.

Zavala met photographer and Duquesne graduate Kelly Bogel at Pittsburgh Filmmakers when she began taking classes there in 2009, and they agreed to work on the project together. Bogel’s familiarity with shooting urban landscapes and her interest in the regrowth of natural life in urban settings over time made her the perfect photographer for the project.

The project officially started when Zavala and Bogel received a grant for the project from The Sprout Fund — a Pittsburgh agency that aims to support innovative ideas in the city. In early 2013, they located the signs they already knew about and captured them using a Calumet Monorail 4-by-5-inch camera. Bogel shot on the weekends and explored different parts of the city, discovering more signs as she worked.

“I would stand at a sign for a good 10 minutes. I feel like there’s a lot you miss passing by,” Bogel said. “The hardest part was making sure the camera was perpendicular to the image. The rest was taking care of the two exposures to make sure they were OK.”

The 4-by-5, large-format camera Bogel used allowed her to capture the signs effectively, even when they were high up on a building.

Sue Abramson, a professor at Pittsburgh Filmmakers who assisted Zavala and Bogel with the exhibit, said shooting with a 4-by-5 camera is one of the best forms of photography.

“You can tilt and correct all the lines and make the architecture of the building look appropriate,” Abramson said.

Bogel said he and Zavala scouted sites for photographs initially, but found more adverstisements while shooting. One sign always led to another.

Because of the wide area Bogel scouted, there’s a diverse array of designs featured in the exhibit, from the color of the signs to the actual content they advertise.

“Some of the signs identify the company, while others are purely advertising,” Zavala said. “I especially like the signs with images, and there are about a dozen of those, but no more.”

Sometimes only a digital print would unravel the mystery of the remaining pigments. After Bogel caught them on film, Zavala would inspect the images digitally and decide which ones to print. The final product is a large reproduction of the advertisement that allows people to view the different aspects of the remaining design up close.

“The big thing I wanted to accomplish was all the subtle variations in color, form and texture. The things you wouldn’t be able to examine by just passing by,” Zavala said. “Our aesthetic was to not manipulate these. For those, it encourages [viewers] to look at subtleties.”

At the beginning of the project they knew of about 10 painted advertisements. By the time they were done shooting, they had 180.

“There are a lot of them in the Strip and Downtown and in places you wouldn’t necessarily think, like Polish Hill,” Bogel said. “Farther out of the city they kind of die out.”

The signs are found in all Pittsburgh communities, from Brighton Heights and Homewood, to McKees Rocks and the North Side. Each one of the 150 locations has a different history. The exhibit is a detailed illustration that tells a story of Pittsburgh’s past.

“It’s not just an art project. It’s a historical artifact and a really great thing for the city to have,” Abramson said.