After her family friend was diagnosed with leukemia, Jessica Cohen saw her community of family and friends come together.

So following their example, she signed up to become a bone marrow donor, adding herself to a list of people who could provide life saving marrow or stem cells to cancer patients.

Cohen, a senior at Pitt, registered as a bone marrow donor after she realized this simple act could one day lead to a match and a chance to save another person’s life.

“I watched a lot of the adults in my life join all these big donor drives, and I realized it was important,” Cohen said.

Now, the national groups that register people to donate bone marrow are expanding, and two of them working to connect donors to patients have reached Pitt’s campus.

These groups — Gift of Life and Be The Match –– are broadening their work amongst Pitt students to get people from diverse backgrounds onto the bone marrow donor registry.

On Monday, Gift of Life held their first donor drive of the year outside the William Pitt Union, where students completed an online survey, swabbed their own cheeks and sent their information to a lab to be officially entered into the Gift of Life donor registry.

“We just want to find people who would likely be willing to donate if they got the life-saving call,” Alyssa Berman, Pitt’s Gift of Life president, said.

Last year, the Gift of Life Club registered 892 people on Pitt’s campus.

According to the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, 60,140 people in the United States are expected to be diagnosed with blood cancer in 2016. Around 70 percent of patients cannot find a suitable donor for bone marrow in their own family, and over 3,000 people die each year due to the inability to find a bone marrow donor match, according to the Institute for Justice.

Daniella Ortiz, president of Pitt’s chapter of Be The Match, said the organization has increased its efforts to enroll college students to increase the diversity of the overall registry.

“A huge part of what we try to do at Pitt is diversify the registry because we do have a pretty diverse campus,” Ortiz said.

According to Berman, one Pitt student was matched with a patient through the registry last year. Because the student’s decision is confidential, it is unknown whether they chose to donate.

Nationally, Gift of Life has chapters at 80 universities and has registered 252,000 donors and made match connections for over 5,000 patients. Cohen said she hopes to be one of those 5,000 matches.

“I would just love to get that call one day,” Cohen said.

Diversifying the donor registry is important because the composition of bone marrow proteins is genetically based, so a patient’s match is usually within their same ethnic group. The probability of finding a donor match drops to 15 percent if the patient is part of a minority group and below 10 percent if the patient is biracial.

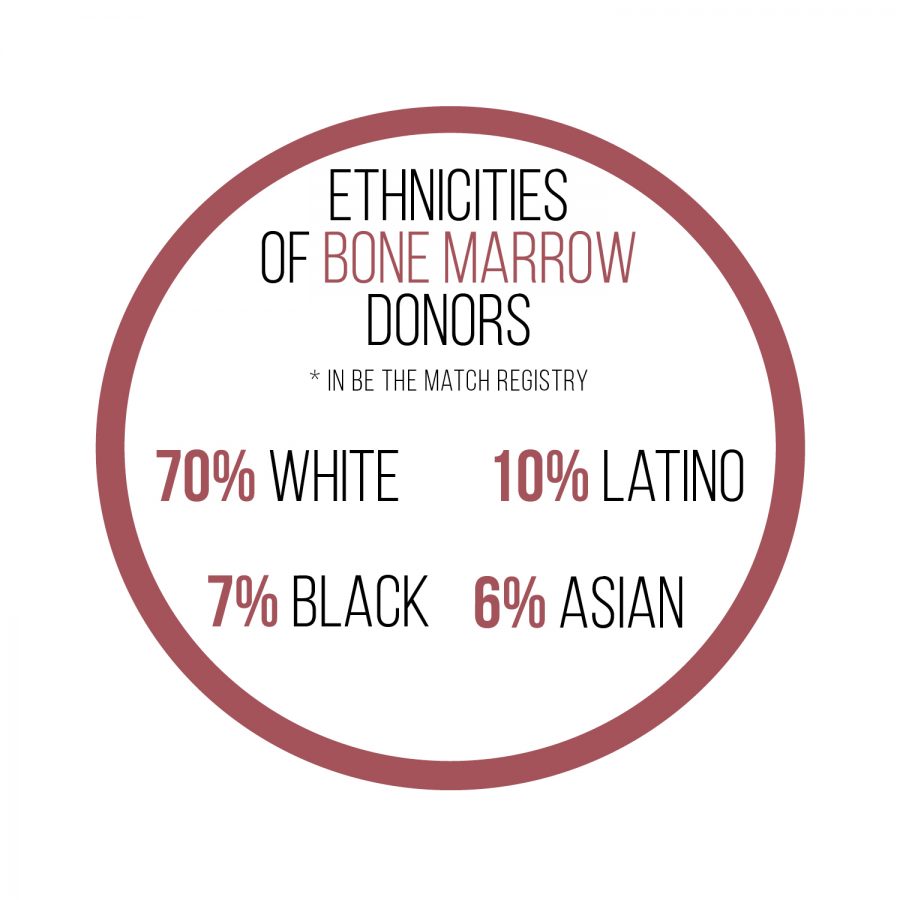

Be The Match has a total of 28 million donors on their national marrow donor registry. Of these donors, 70 percent are white while 10 percent are Latino, 7 percent are black and 6 percent are Asian.

Because of the low variability of donor ethnicity, a black patient has only a 66 percent chance of matching with a donor, while a white patient has a 97 percent chance of matching, according to Be The Match.

If a patient begins looking for a donor through one organization and finds no one, that registry will then connect the patient’s information to other registries to continue the search for a match. Worldwide, there are 72 donor registries.

“If you are in one registry, you are in them all because they work together,” Berman said.

In order to increase the number of registered donors, Gift of Life and Be The Match also aim to expel the myth that being on the registry means enduring a painful donation procedure.

Traditional bone marrow transplants, which uses a needle to draw liquid marrow from the pelvic bone of the donor, only occurs in about 20 percent of cases. The majority of donations are nonsurgical. In these procedures, the donor’s blood is taken from one arm, the healthy stem cells from the blood are filtered out to to be given to the blood cancer patient and the remaining blood is returned to the donor’s other arm, according to Be The Match.

Ortiz said that she quickly learned that people are very confused when they see advertisements for a “donor drive.”

“When we ask people to become a donor, they think that they are going to have their bone marrow taken, like right then and there,” Ortiz said.

In reality, agreeing to become part of the bone marrow registry simply entails taking a cheek swab sample and filling out a paper that describes some personal specifics, such as gender and ethnicity. The swab kit and information is sent to the Be The Match lab and entered into the national registry for the organization.

According to Be The Match, a sample is a match if both patient and donor have the same HLA proteins –– markers that differentiate between cells that do and do not belong in the body. A donor’s HLA proteins need to be almost identical so that the patient’s body doesn’t reject the donation.

Donors remain in the database for a lifetime and will be contacted if their profile matches a patient’s. Ortiz said the effort of registering and then possibly donating is minimal in comparison to its effects on cancer patients’ lives.

“In that couple of hours, you have saved someone’s life,” Ortiz says. “[That] is such a cool thing.”