The historical reporting in this story is from information found in the University’s Special Collections at Hillman Library, unless otherwise noted.

Every day, Pitt students wake up in bedrooms on Neville Street or dine at restaurants on Craig Street or head to class by way of Bates or Bouquet streets.

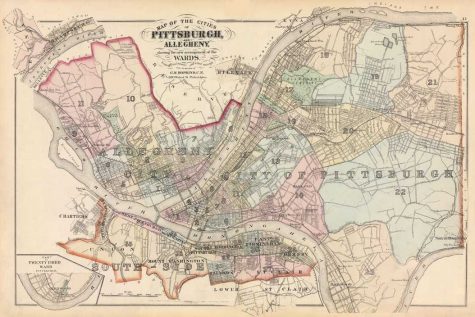

Those roadways –– which city planners named about 150 years ago –– are as integral a part of Pitt’s extended campus as the Cathedral of Learning. And they’re named after men with varied histories.

Some of those histories are darker than others. Bouquet Street, for example, is named for Col. Henry Bouquet, who was connected with the distribution of blankets infected with smallpox to Native Americans in the 1760s. Just outside of campus, Neville and Craig streets were named in honor of the largest slave owners in western Pennsylvania at the turn of the 1800s.

The University buildings which share names with these streets –– including the Bouquet Gardens apartments and Craig Hall –– were named for their location on the street rather than the men in question, according to University spokesperson John Fedele.

Fedele did not answer questions via email or by phone about whether the history of the street names affected Pitt’s decision to name the buildings or if administrators would consider that history now.

The Neville and Craig families owned numerous properties and a large amount of wealth, which allowed Pittsburgh to grow and establish itself prior to and throughout its founding as a city in 1816. Bouquet defended the land that eventually became Pittsburgh for the British during the French and Indian War, which ran from 1754 to 1763. In January 1806, Tarleton Bates was the last man in Pennsylvania to be killed in a duel when Thomas Stewart shot him at the far end of what is now Bates Street.

Georgetown University came under fire earlier this year for benefiting financially from the sale of nearly 300 slaves in the 1800s, raising a debate about whether or not public institutions should make reparations for the history of their namesakes.

Aminata Kamara, president of Pitt’s Black Action Society, said she understands that Pittsburgh is trying to stay connected with its history by naming streets after influential characters.

“This is their history,” Kamara said. “It’s messed up, and I don’t agree with it, but it’s their history. And if Pittsburgh wants to continue being a historical city … good and bad, they keep their history so people can learn from that and reflect on it.”

Bouquet Street

On Columbus Day, Pitt students have protested the celebration of Christopher Columbus. Instead, some dub the second Monday in October “Indigenous Peoples’ Day,” and celebrate the people who lived here before Columbus arrived.

Last year, students and community members marched from Bigelow Boulevard to the Columbus statue outside Phipps Conservatory, where they listened to speeches about the effects of colonization on indigenous people, only a few blocks away from the street named for a different attack on indigenous people.

Bouquet — after whom Bouquet Street is named — is most famous for his capture and defense of Fort Pitt against the Native Americans, a turning point during the French and Indian War.

The French allied with the Native Americans and fought against the British from 1754 to 1763 due to a land dispute. He continued as Colonel during the immediately ensuing Pontiac’s War from 1763 to 1766 — an attack by a loose confederation of Native Americans upset by the British victory over the French.

The most famous battle of the war occurred at Bushy Run when Native Americans ambushed an envoy on its way to Fort Pitt, with the intention of backing up a garrison. Bouquet managed to hold out against the ambush and reclaim Fort Pitt located at what is now Point State Park in downtown Pittsburgh.

Letters written in the summer of 1763 between Henry Bouquet and Jeffrey Amherst –– commander in chief of the military forces serving in New York –– indicate Bouquet administered smallpox blankets to the Native Americans during Pontiac’s War.

“I will try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets that may fall in their hands, taking care however not to get the disease myself,” Bouquet wrote in a July 1763 letter to Amherst.

Thirteen days later, Bouquet sent another letter to Amherst, saying “all your directions will be observed.”

To administer smallpox blankets, British soldiers took blankets taken from soldiers who had died of smallpox and had contaminated their blankets with the disease. The surviving soldiers gave the contaminated blankets to Native Americans in an attempt to pass the disease on to the Native American population.

According to the Amherst Archive Center, Amherst advised Bouquet to use the smallpox-infested blankets after Bouquet had already administered them. The Center disputes the idea that the blankets had any effect in transmitting the disease.

Bates Street

Near the bank of Monongahela River at the end of the street now bearing his name, Tarleton Bates died in the last duel in Pennsylvania in January 1806.

In honor of the man killed in the duel, the street stretching from Bouquet Street to Second Avenue became Bates Street and bookmarked the story for future generations to explore.

In 1805, Bates was walking down Market Street one day when he passed Ephraim Pentland on the street. Bates was a rising political figure in the city and Pentland, then an editor at the paper, Tree of Liberty, frequently published insults about Bates. The men exchanged heated words and Bates physically assaulted Pentland. Pentland sent Thomas Stewart, a local merchant, to demand an apology from Bates. For days, Bates refused to apologize, eventually angering Stewart so much that he challenged Bates to a duel. Pentland, who was of a lower social class than Bates, was not considered a worthy duel opponent for Bates.

Stewart and Bates met on Jan. 8, 1806, on the end of what is now Bates Street, about where Craft Avenue is, and took their stances 12 paces apart. Both men fired once and both missed. Dissatisfied, they began round two of the duel. This time, Stewart’s aim improved and his shot hit Bates in the chest. Bates died within the hour. Fearing legal repercussions for killing another man, Stewart fled Pittsburgh and never returned.

Craig and Neville streets

On South Craig Street, students line up outside Union Grill or sit behind the open garage doors in Coffee Tree Roasters.

Parallel to South Craig, Neville Street is mostly private housing for both students and families, named after military men and central figures during the Whiskey Rebellion, a farmer revolt against taxes on distilled spirits in 1791 to 1794.

Gen. John Neville served alongside Gen. Edward Braddock during the French and Indian War, while Presley Neville was secretary for Marquis de Lafayette, the French general who aided the Americans in the Revolutionary War. Maj. Isaac Craig also fought in the Revolution and married Amelia Neville, John’s daughter.

Rob Windhorst, board member and former president of the Neville House Associates — a historical society in Pittsburgh’s South Hills –– said the Craig and the Neville families were two of the wealthiest landowners of southwestern Pennsylvania. They had an overwhelming influence over the city’s early days at the turn of the 1800s.

John and Presley Neville and Isaac Craig were also the three largest slave owners of western Pennsylvania, owning 28 slaves between them in 1780. By 1800, the three men owned double the amount of slaves, according to Windhorst. By 1806, all slaves were freed through gradual emancipation.

As time went on, however, tides turned. Both Neville’s and Craig’s children opposed their parents’ views and worked to end slavery by establishing a staunch abolitionist position at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, then called the Gazette, in the first half of the 19th century.

With passing time, Kamara, the president of Pitt’s Black Action Society, said history has been reframed in a positive light.

“We’re told one thing so we can feel better, to help us digest our history—but our history’s just horrifying.”

Hanson Kappelman, the co-chair of Oakwatch –– an Oakland neighborhood committee –– said history is like a data bank, where Pittsburghers can see how people’s beliefs have changed over time, even if they don’t agree with them.

“[History is] a record of people’s good and bad intentions, and the results of them doing things we may or may not agree were valuable things to do,” Kappelman said. “It’s easy to just assume the way things are now is the way it’s always been.”

All historical information in this story was found through the following sources, unless otherwise noted:

History of Colonel Henry Bouquet and the western frontiers of Pennsylvania, 1747-1764

by Darlington, Mary C. (Mary Carson), 1824-1915

Letters between Jeffrey Amherst and Henry Bouquet, Summer 1763