If you’re looking for something to take your mind off of looming finals week exams, the University of Pittsburgh Art Gallery, located in the Frick Fine Arts Building, is showing two concurrent exhibitions through Dec. 9.

Organized by graduate students in Pitt’s history of art and architecture program, “Chinese Apartment Art: Primary Documents from Gao Minglu’s Archive, 1970s-1990s” takes a look at works following China’s Cultural Revolution. The other collection, “Paradoxes of Play: Concrete and Conceptualist Proposals from Brazil and Beyond,” invites patrons to interact with the art as part of this year’s undergraduate Museum Studies Exhibition.

The Pitt News sent two writers to the the Frick Fine Arts Building to review the exhibits.

“Paradoxes at Play: Concrete and Conceptualist Proposals from Brazil and Beyond”

At some museums, touching a piece of art can get you escorted out of the building. Sometimes, being too close or using flash photography is enough to warrant a warning in hallowed halls of fine art nationwide.

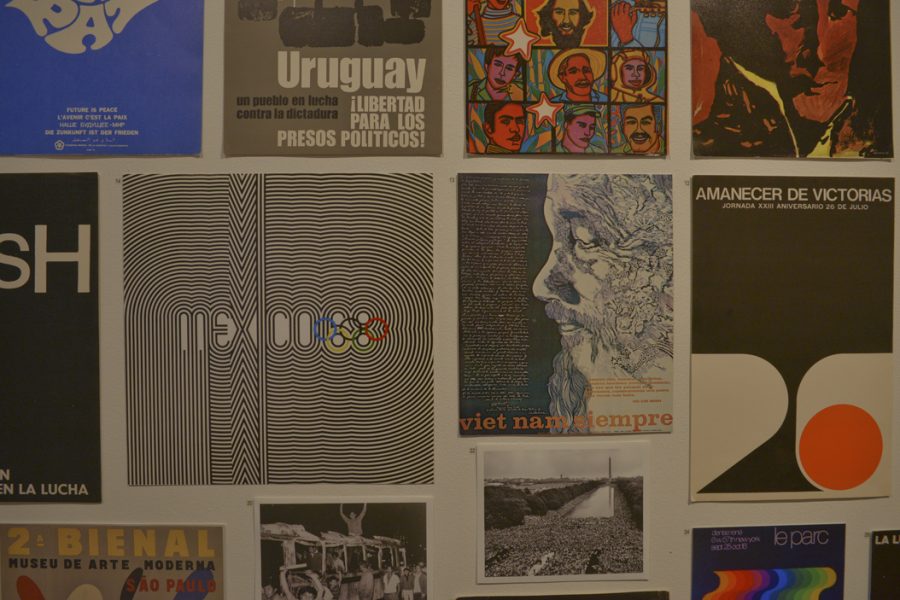

But in the Frick Fine Arts building, the variety of artists in “Paradoxes at Play: Concrete and Conceptualist Proposals from Brazil and Beyond” — an exhibit similar to the work on display by Hélio Oiticica in the Carnegie Museum of Art — are just the opposite. They want you to touch.

Conceptualist art relies on the idea that the idea behind an art piece is more important than the piece itself. Especially popular from 1960 to 1980, conceptualism began with Marcel Duchamp, who also had one foot in Dadaism — a sister art movement associated with unorthodox and sometimes absurd art.

In the Frick Fine Arts Gallery, the front room includes purely concrete and interactive pieces — like “A Cutting Proposition.” The piece encourages visitors to create and cut paper into a Mobius strip, a rectangular surface that looks like a twisted racetrack.

The second room is less tactile. There is no single theme holding the pieces together besides the broad conceptualist movement. Its ideas start with anti-censorship art from Argentinean Jaime Davidovich’s “Blue, Red, Yellow,” in which televisions are covered in colored tape. There is also a collective project challenging art mediums by using a human body as a canvas in “circulo vermelho sobre o branco (Red Circle on White).”

The exhibits can be isolating and vague. Without historical context, some can seem like sweeping statements instead of specific strong commentary. For example, Davidovich’s 1970s work is more reflective of Argentina’s history — especially the tumultuous dictatorship and revolutions of the 1970s and the country’s 1950s censorship laws. Furthermore, several pieces are purely in Spanish or Portuguese without translations.

In an area where many visitors do not speak Spanish or Portuguese, the lack of translation could hinder a gallery-goer’s experience or be interpreted as a commentary on the division of language in art, which, in this case, was overcome by the interactive part of the pieces. For example, Octavio Paz and Vicente Rojo’s 1968 “Discos Visuales (Visual Discs)” gives visitors a chance to hold the art. The exhibit consists of small paper discs layered on top of each other with directions to turn the discs and reveal different cutouts. The cuts revealed Spanish phrases or words that, when combined together, make simple poetics that a viewer with just a beginner’s competency of Spanish can understand.

“Discos Visuales” is at the core of what “Paradoxes of Play” seems to want to achieve. The art is shaped like small vinyl discs, which gives an element of play. The art doesn’t take itself too seriously. Like the Mobius strips, museum-goers are encouraged to “play” with the concepts and with the art.

The paradox lies in what we know of museum art: It is distant. It is a world beyond us. It is “high” art because it is beyond the average person’s talent or comprehension level. Yet, here is art begging the patrons to hold it. Play with it. Get meaning out of it in your own way.

— Ellen Kruczek

“Chinese Apartment Art: Primary Documents from Gao Minglu’s Archive, 1970s-1990s”

It’s Nov. 26, 1994. Chinese artist Shi Yong, using his friends’ apartments as reference points, wanders from one Shanghai phone booth to another for 12 hours straight as a part of his installation titled “Mobile Leaps: Twelve Hours.”

The University Art Gallery’s exhibition of Chinese Apartment Art calls to mind the small and square map of Yong’s improvised stroll more than 15 years ago. “Mobile Leaps” is part of a collaborative postcard installation titled “November 26th as a Reason,” which fellow artist Geng Jianyi, known for his politically charged artwork, spearheaded. Both Yong and Jianyi are part of a contemporary art movement in China that sprouted in the mid ‘80s called “apartment art” that focused on household displays of art shared between friends and close circles rather than displayed in a salon-style gallery setting.

The movement is, in part, borne out of practicality.

Even as China grew apart and from Mao Zhedong’s authoritarian regime, political tensions were still high enough that politically charged art was kept in select circles. The University Art Gallery curated a timeline of the collective exhibition as China approaches two decades after the end of the Cultural Revolution.

China’s Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966, saw a mass destruction comparable to the fire that engulfed the Library of Alexandria in 48 B.C. Red Guard groups — Communist revolutionaries recognizable for their red arm bands — burned everything anti-proletarian or bourgeois within reach, including centuries of historical relics, art and literature. The event completely upheaved China’s traditionally hierarchical society, also halting the country’s industrialization in 1976, the year of Chairman Mao Zedong’s death.

“Chinese Apartment Art” is a collection of work archived by professor Gao Minglu and exhibited by his graduate student class that visited Shanghai for a special topics seminar.

Minglu’s career as an art critic and scholar came to fruition in the mid ‘80s, around the time “household art” rose to popularity. After earning his Ph.D. in Harvard, Minglu now teaches abroad and works from his office in the Frick Fine Arts building. The exhibition follows the exploration of art forms from the ’70s to the ’90s in China. More profoundly, the exhibit narrates an art movement as far-reaching and rapidly developing as the Chinese people and their country.

The exhibition elicits senses of wonder, elation and uncertainty that perhaps Yong also experienced as he forged an unfamiliar path through familiar streets — the sense of witnessing a city and country that is rebuilding itself.

Unlike “Paradoxes of Play,” which invites participation, “Chinese Apartment Art” keeps the viewer at arm’s length. The most intimate display is a salon-style cluster of original oil paintings from the ’70s and ’80s. Everything exhibited from the ’90s uses reproducible mediums — postcards, films, photographs — to reflect the need for closed circles and discrete distribution under increased government surveillance and political tension.

Any closeness the installations create are appropriated through a camera lens or drawn depiction. Whether by pure circumstance or intention, outsiders of the Chinese “apartment art” world are rendered, at best, voyeurs. This leaves a lot of questions about the underground movement: Where was the art distributed? How exclusive were apartment art circles? How sincere were the apartment artists’ attempts to engage with the public?

Even without giving specific answers, the exhibit is successful in conveying basic, universal themes. For example, in a series of short films, He Chengyao uses art as a means of navigation. She takes her top off while walking along the Great Wall in “Opening the Great Wall” and films herself undergoing acupuncture in “99 Needles.” It’s all a reminder of the personal nature of artistic expression, even under the intensity of China’s political climate.

— Isabelle Ouyang