When it comes to the origin of the television, there are two competing storylines.

One story begins with Russian-born Vladimir Zworykin, lying sick in bed in his family’s mansion, staring out the window. The other begins in Utah with Philo Farnsworth, working on his family’s ranch, plowing a field of sugar beets. In between, there are stops in Paris, Pittsburgh, San Francisco and Camden, New Jersey. But both tales end in 1939, in a United States patent courtroom and depending on who you ask, one of these two men — now both deceased — is the “Father of Television.”

The Origins: Vladimir Zworkyin

Frederick Olessi of Lawrence, New Jersey, met Zworykin in 1968. Olessi, now 83, was working as a technical writer at Radio Corporation of America in Princeton, New Jersey, and eventually became Zworykin’s close friend and biographer.

Zworykin, born in 1889 in Murom, Russia, was 6 years old when a serious illness catapulted his vision for television, according to Olessi.

The Zworykin family — wealthy compared to the rest of the city — used their money to give their son the best care they could afford. His father built a small infirmary for him in the top floor of their mansion, and Zworykin would spend his days gazing out of his window.

“He saw people stringing wires on poles and asked his father what that was,” Olessi said.

“Well, that’s a telephone line,” Zworykin’s father replied.

“What’s a telephone?” Zworykin asked.

“Well, it’s something that carries a voice over lines.”

“Does that go all the way around the earth?

“Of course.”

“All the way into the universe?” Zworykin asked.

“I don’t see why not,” Zworykin’s father replied.

In that moment, Zworykin began dreaming about a world where all kinds of information would travel farther than any man could.

Stuck in that room in the attic of his mansion, he didn’t have much to do or many people to talk to, so he turned to his telescope for entertainment.

“He was watching, always, the moon,” Olessi said. “And he asked, ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful if something could be created that we could see the dark side of the moon?’”

After recovering from his illness, Zworykin proved to be an apt scientific thinker and eventually attended the Saint Petersburg Institute of Technology.

As Russia headed into a civil war, Zworykin began to realize it was no place to continue his research. So he prepared to leave his homeland in 1918, looking instead to Pennsylvania.

“When he escaped from Russia, he knew two English words: Westinghouse and Pittsburgh,” Olessi said.

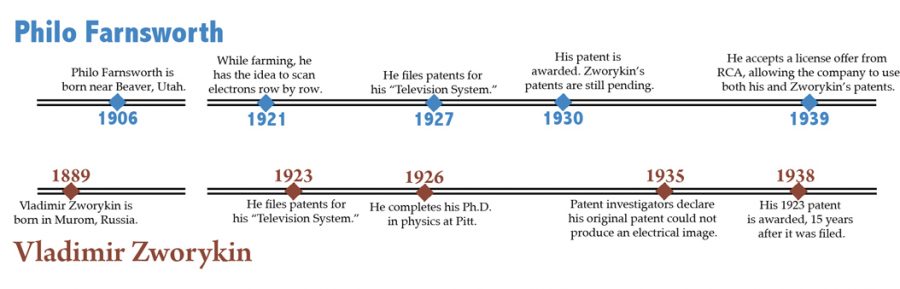

With his wife, Zworykin made his way across the world to Pittsburgh, where he was hired in 1920 as an engineer at Westinghouse Research Laboratories. During this time, he also started his Ph.D. in physics at the University of Pittsburgh, which he completed in 1926.

As Zworykin moved across the world and began his research in earnest, a Mormon farm boy, Farnsworth, was cultivating a similar vision.

The Origins: Philo Farnsworth

Born in Utah in 1906, Farnsworth split his time growing up between high school classes and his family’s ranch.

Paul Schatzkin — author of “The Boy Who Invented Television” and a staunch supporter of Farnsworth as the “Father of Television” — said that Farnsworth first conceptualized an electrical television in the summer of 1919, when he was just 13 years old.

“[Farnsworth] was plowing a sugar beet field, and he looked behind him and he saw all the rows that he had plowed,” Schatzkin said. “And that was the moment that the inspiration struck him to use a cathode ray tube to create an electrical image and then scan that row by row just like the rows in his field.”

Farnsworth presented the idea to his mentor and chemistry teacher at Wrigby High School, and his teacher asked him to sketch a schematic design of the concept, which the teacher would hold onto for 10 years.

“Every bit of video technology on the planet today can trace its origins to that drawing,” Schatzkin said.

The Patents

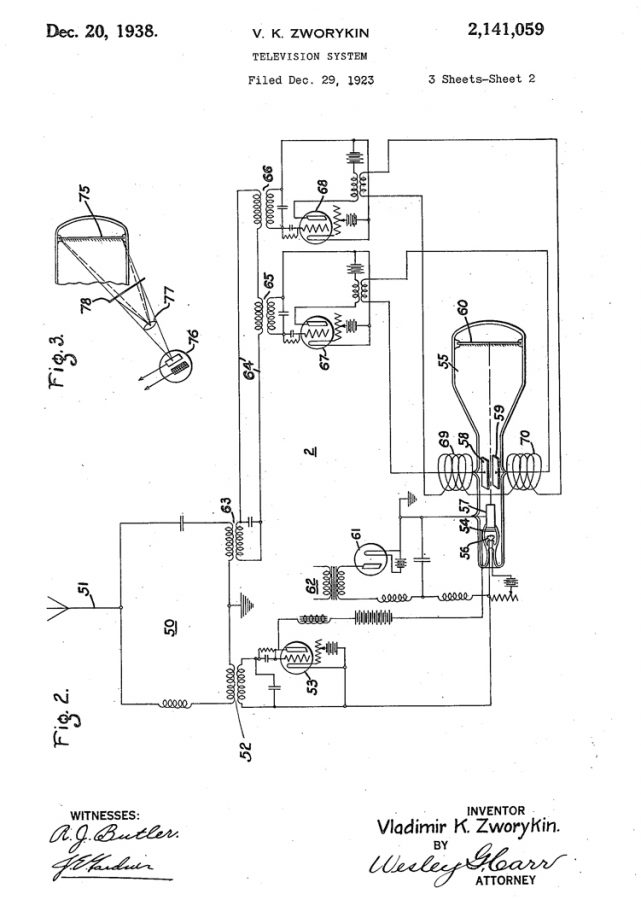

Zworykin worked tirelessly at Westinghouse on a device that would eventually become the “iconoscope.” Zworykin’s device used cathode ray tubes to receive an input and then shoot electrons to recreate an image on a fluorescent screen.

Zworykin applied for patents for his design of a “Television System” in 1923 and 1925. Just before submitting these patent applications, in the summer of 1923, Olessi said Zworykin demonstrated the device to his superiors at Westinghouse.

“It was an extremely crude image of a train coming up the Monongahela on that screen,” Olessi said. “His boss didn’t know what the hell he was seeing and said, ‘Can’t you put him to work on something more interesting?’”

Schatzkin sees this as evidence that Zworykin’s 1923 iteration of the iconoscope was bogus. In Schatzkin’s online publication, “The Farnsworth Chronicles,” he disagrees with the interpretation that the Westinghouse executives were “too shortsighted” to appreciate Zworykin’s work.

“It seems more plausible to conclude that what they saw showed little promise because it simply didn’t work,” Schatzkin said.

Farnsworth, at this point, had moved to San Francisco and was working out of his own laboratory at 202 Green St. In 1927, while Zworykin’s patents for the iconoscope were still pending, Farnsworth applied for his own patent for his design of a “Television System.”

The most important element of this patent application was its “image dissector,” an element that would create an “electron image” within the television that could then be scanned by an electron beam and presented on a screen — a different technology than Zworykin’s invention.

After three years in limbo, Farnsworth’s patent was awarded in 1930 and Zworykin still hadn’t heard back about his.

Zworykin accepted a job opportunity from David Sarnoff — the head of RCA — and moved to Camden, New Jersey, to continue his work on the electronic television.

Through Sarnoff, Zworykin heard about Farnsworth and his work on television systems on the West Coast. Zworykin traveled to Farnsworth’s lab to see his work in 1930. Both Olessi and Schatzkin corroborated a famous sentence that Zworykin uttered in the Green Street laboratory that day:

“What an interesting idea. I wish that I might have invented it.”

Schatzkin sees this statement as Zworykin admitting defeat. Olessi says it was just an example of Zworykin’s “encouraging” personality.

The Courtroom

What followed was a bitter battle in U.S. appeals court between RCA and Farnsworth. With television on the brink of becoming marketable in 1934, RCA’s attorneys challenged Farnsworth to prove that his design was paramount to the development of the electronic television.

Dan Michelson is the project archivist for processing the Sarnoff Collection — a body of artifacts and papers surrounding RCA’s history — at Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Delaware.

According to Michelson, Sarnoff and RCA went through many “patent battles” similar to the one between Zworykin and Farnsworth.

RCA argued that research from Zworykin’s team in 1930 formed the most crucial part of the electronic television. Farnsworth, meanwhile, went back to his high school teacher and retrieved the 1919 sketch of the image dissector.

With this and his patent in hand, Farnsworth argued that his 1927 “image dissector” was the true pivotal element and that the technology from Zworykin’s 1923 patent application could not successfully create an electronic image as his could.

The patent investigators seemed to agree with Farnsworth and asked RCA to show documentation of Zworykin producing an electronic image prior to Farnsworth’s patents.

Unfortunately for Zworykin and his attorneys, only anecdotal evidence existed of the 1923 demonstration of the train puffing along the Monongahela river.

Without any evidence, patent investigators declared in 1935 that Zworykin’s original patent could not successfully produce an electron image as RCA had claimed.

But the battle raged on. RCA had enough money and attorneys to keep the appeal process going. The patent office decided in 1938 to retroactively award RCA and Zworykin a patent for their 1923 patent application. In addition, RCA offered Farnsworth a license so it could lease his patents and use them alongside Zworykin’s.

“In 1939, Farnsworth was exhausted and accepted a license from RCA,” Schatzkin said. “RCA persisted and continued to have the power and the influence to tell whatever story they wanted.”

Benjamin Gross, whose Ph.D. research focused on RCA’s history, said Farnsworth pursued the process of innovation in an “older” style than RCA did.

“[Farnsworth] was an independent inventor in the classic sense who wanted to take his technology from the drawing board to the marketplace while maintaining complete control over it,” Gross said

Zworykin, on the other hand, led a large team of RCA engineers who all worked on different elements of the television system.

“Zworykin wasn’t the sole inventor. He would agree, there were many other people involved,” Gross said.

Olessi said the desire to view Farnsworth as the creator is just a temptation to fit an underdog narrative — to believe that the modest farm boy could win out over the aristocrat.

“It sounds good as poetry, but not as prose,” Olessi said.

The Dark Side of the Moon

Today, the debate hinges not on royalties, but on who deserves credit as the inventor, the visionary, the Father.

Michelson called this ongoing debate “arbitrary” because a large number of people were involved in the creation of the television.

“In any sort of modern technology like this, there’s hardly ever one person who’s responsible,” Michelson said. “Neither of them could have done anything on their own.”

Aside from all the controversy, there was one moment that both scientists got to experience and, in a sense, share.

It was 1969, and Neil Armstrong landed on the moon. The landing was broadcast to the world late at night, but both Zworykin and Farnsworth stayed up to watch in their respective homes.

In a 1996 interview conducted by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Farnsworth’s wife Elma “Pem” Farnsworth relayed what he had to say about the moon landing:

“Phil turned to me and said, ‘Pem, this has made it all worthwhile.’”

Zworykin, too, watched the moon landing, with Olessi by his side.

“It was my incredible honor to drag [Zworykin] out of bed that night,” Olessi said. “And sit with him so he could see, on a device that he created, the dark side of the moon.”