Pitt announced a new contract with the pharmaceutical company Bayer on Jan. 11. The contract will unite Bayer and the School of Medicine to research early indications of heart, lung and blood disease. The cooperation has the potential to offer innovative advancements to medicine, as early warning signs can greatly improve the success of treatment.

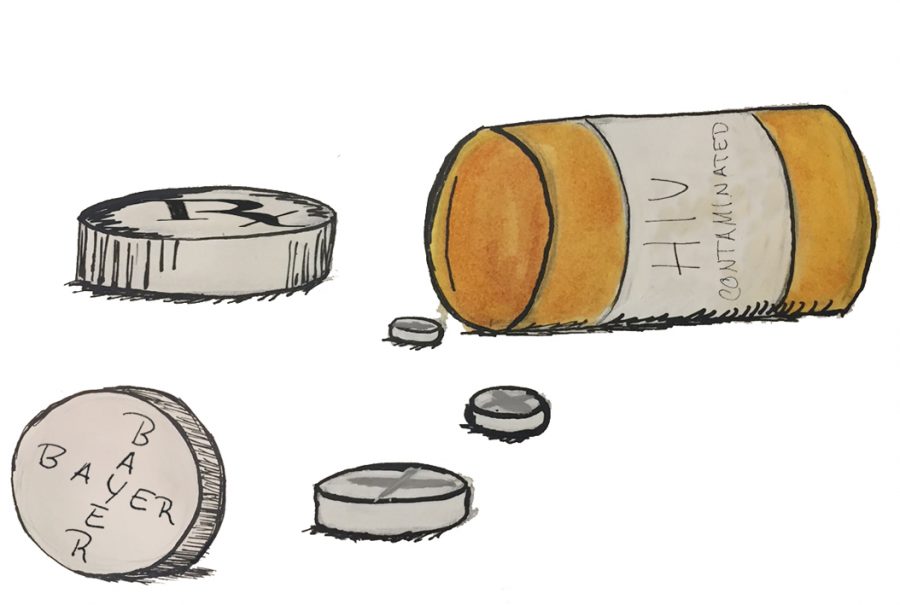

Intrigued, I dug a little deeper into Bayer’s research and development history. I learned about a particularly suspicious series of events in the 1980s that connected Bayer to the spread of HIV-contaminated medicine in Asia and South America.

University spokesperson Anthony Moore said he would reply for comment Thursday but did not respond in time for publication.

The contentious period of Bayer’s history began in the 1970s. The company’s biology department, Cutter Biological, was the primary producer of the medication Factor VIII from 1970 until 1985. The medication replaces the factor protein responsible for clotting blood, a protein hemophiliacs lack. Producing the medicine involves using plasma from blood donations — a financially incentivized market, particularly in prisons.

Cutter Biological bought the blood to produce Factor VIII from the Arkansas Department of Corrections. Prisoners were paid $7 per pint of blood, which sold on the international plasma market for over $50 a pint, directly profiting the Arkansas Department of Corrections.

HIV testing wasn’t developed until 1985, so Bayer had no means of testing the blood prior to this. But the HIV infection rate of incarcerated individuals is over five times that of the general population, meaning the chances of drawing infected blood from prisons was known to be high.

Cutter Biological only began producing a heat-treated version of Factor VIII — which eliminates infections in the blood — in the United States in 1984 after concern that the old medication was responsible for infecting hemophiliacs with HIV. The backlash connecting the Bayer medication with increased rates of HIV infection in hemophiliac patients caused the company to discontinue its use in the United States. But Bayer continued selling the old medication in Asian and Latin American markets for over a year after ceasing sale in the United States, citing their consideration that pre-existing, price-fixed contracts would make the old medicine cheaper to produce.

Estimating the human toll of this decision is difficult, since an AIDS test was not developed until the mid-1980s. The New York Times reported in 2003 that over 100 individuals contracted HIV in Taiwan and Hong Kong alone after receiving the contaminated Cutter medication.

Bayer’s comments maintain that they “behaved responsibly, ethically and humanely” in selling the old medication overseas, even though they had a safer version available in the United States. Over $600 million in settlements had been paid as of 2011.

Other than comments made to The New York Times and the various settlement deals, there’s been little news about the Bayer controversy and hardly any criticism of the company for their decades-long silence and ignorance of the ordeal.

Cutter Biological collaborated with the U.S. government in a 1985 meeting. Dr. Harry M. Meyer, Jr., the FDA’s regulator of blood products, requested that the issue be “quietly solved without alerting Congress, the medical community and the public,” demonstrating both Bayer and the FDA’s desire to keep the scandal secret.

The documents detailing the incident were at one time obtained by the New York Times but are no longer publicly available. Dr. Sidney M. Wolfe, one of the United States’ most prominent advocates for medication regulation, said that they were “the most incriminating internal pharmaceutical industry documents” he had ever seen.

The unwillingness to accept responsibility or produce an apology is unacceptable. The professional responsibility of accepting consequences for wrongdoing is a common act in business and international relations.

President Obama made a visit to Hiroshima in May 2016 to pay his respects and offer his sympathy for the victims of the 1945 atomic bombing that preceded the end of World War II. It is an admirable and ethical custom for Obama to accept responsibility for the action and offer his condolences despite his complete lack of involvement.

Chipotle’s response to their 2015 E. coli outbreak is an even more topical example of professional responsibility. The CEO of Chipotle, Steve Ells, took responsibility for the entire scandal. If he hadn’t apologized, their company would have faced unrelenting consumer backlash. Contrast this to Bayer’s approach: affirming that their decisions were responsible, ethical and humane and had zero negative repercussions on their consumers.

But these decisions were irresponsible, unethical and inhumane. Bayer never faced the consequences of their actions, and no one forced them to, either. While Bayer’s record since the 80s is blemish-free, the company should still acknowledge this ethical conflict.

Bayer should, at bare minimum, retroactively issue an apology or admission of responsibility to the victims of Factor VIII. By failing to apologize for their actions, Bayer refuses to admit that infecting developing countries with HIV is impermissible. People’s trust in and dependence on pharmaceutical companies is understandable, as many rely on medications for their health. This trust lets the industry off the hook too easily, enticing other companies to prioritize profits over patient health. This must not be tolerated.

Bayer’s actions have set a horrifying precedent: that we can trust Chipotle more than pharmaceutical companies and the U.S. government. While the research that the University and Bayer will collaborate on will surely make advancements in preventative medicine, the University should be aware of the ethical implications of entering a partnership with a company unwilling to accept professional responsibility for infecting hemophiliacs with HIV.

Pitt and Bayer can make major scientific advancements, but they need to do so ethically and responsibly.