In the haziness of morning, before his mind clears for the day, 70-year-old Harish Saluja draws what he can remember of his dreams on a three-by-five-inch index card.

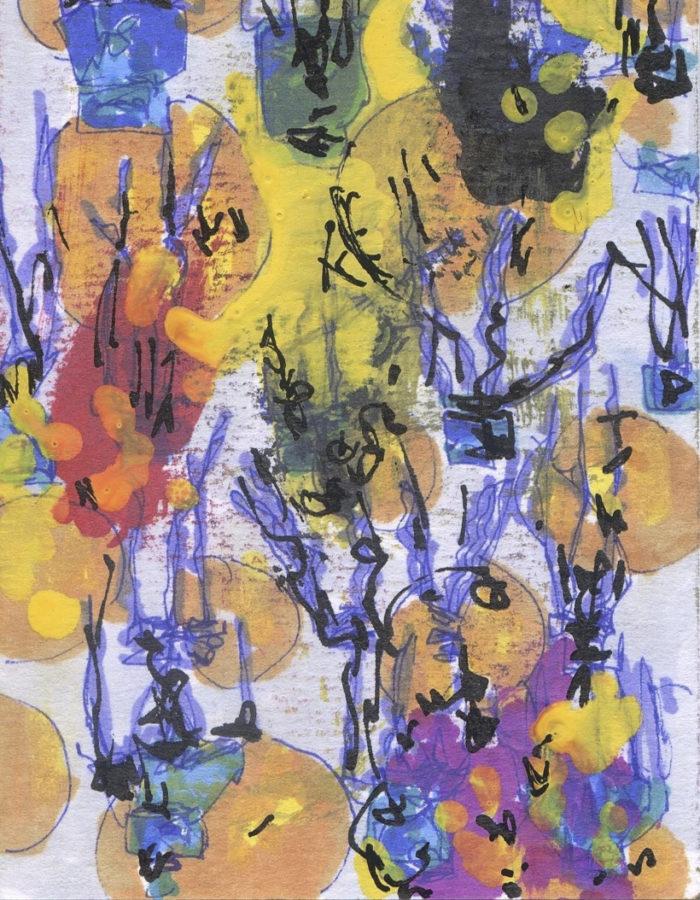

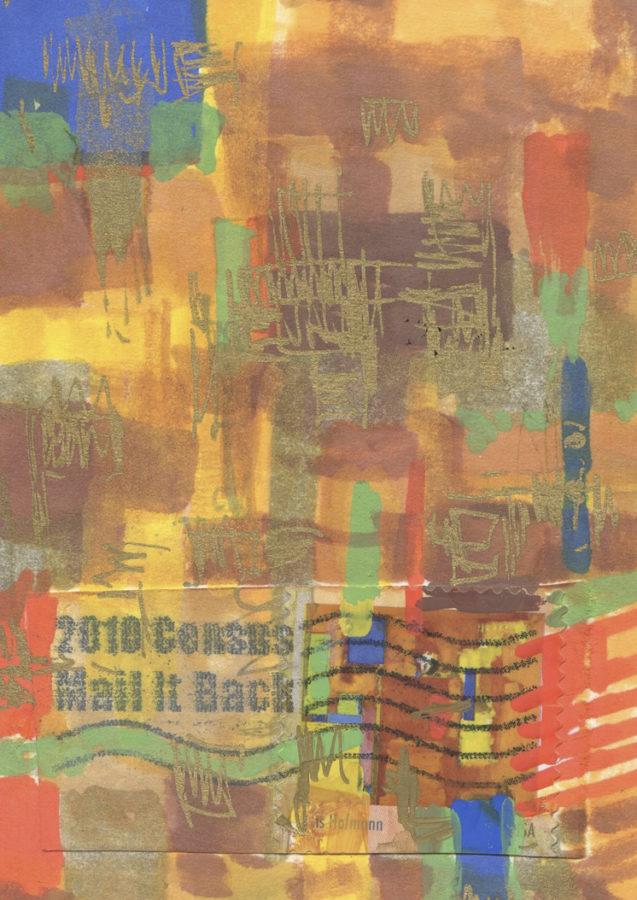

Saluja has been doodling for decades, using an assortment of about 100 markers to record his abstract musings — circular blobs overlaid with splatters of paint and abstract shapes resembling jellyfish, or layers of roughly rectangular shapes in orange, green and blue. He converts them into larger canvas pieces, which are variations of the traditional mandalas — intricate geometric patterns that represent the universe in Hindu philosophy.

The three-by-five-inch index cards — called Miniatures — lack the rigidity of repeating geometric patterns seen in his large-scale canvases of mandalas, and detour through his streams of consciousness. The Miniatures are small abstract pieces, and until March 19 are on display in sets along the walls of the Lantern Building, a small and intimate gallery space in the center of downtown Pittsburgh. In the middle of Saluja’s exhibit stand two tables with an assortment of Miniatures under the glass tops. The Miniatures on the tables are free from the strict groupings of the framed Miniatures on the walls.

Aside from charting his consciousness, there isn’t much of a deeper meaning to this series, Saluja said.

“These doodles hold no purpose — they’re just fun colors and shapes,” Saluja said. “Often I give them as gifts.”

Saluja is the founder of the Silk Screen Asian Arts and Cultural Organization located in the Strip District, which shares Asian culture and art within the city of Pittsburgh. In addition to his art work, Saluja has worked as a filmmaker and co-hosts the weekly “Music from India” show Sunday nights on WESA, a Pittsburgh public radio station.

Jim Knights, a retired FBI agent and long-time friend of Saluja’s, said Saluja is successful in both business and art in part because of his ability to shift modes between the two worlds.

“In his art he improvises, [but] in business he doesn’t shoot from the hip,” Knights said.

After seeing the number of artworks in the Miniatures exhibit, Knights was surprised at how prolific of an artist Saluja is, particularly since Saluja attended the Indian Institute of Technology in Kharagpur — one of India’s most respected engineering schools. This set Saluja up for a lucrative career in engineering, until he retired from that industry in the 1970s.

“He left a highly paid job to be a starving artist,” Knights said. “He’s an artist at heart, that’s how he is.”

Knights has bought Miniatures from Saluja over the years, and although Knights doesn’t have a trained eye for art, Saluja’s arrangement of colors is still striking, and he’s drawn to the abstractions.

“I just liked his art and wanted to support Silk Screen,” Knights said. “One piece looked like souls of the departed going up and down — it really struck me.”

Saluja paints his mandalas while he listens to either jazz or raga — a style of Indian classical musical formed around eight notes. The patterns of Saluja’s art are improvised around this pattern of eight, and each framed set includes eight pieces of art, which share a frame because their patterns are similar. They’re thematically linked, and the open table arrangements are freeform.

Some Miniatures are purely abstract, with patterns in swirls of colors or lines. Others display animals — chiefly birds — or Japanese or Indian nobles in great palaces of millennia ago.

Miniature art is a court tradition in the East, according to Saluja. Hundreds of traditional miniature pieces of art are on display at the Taj Mahal and also in Iran, where this tradition abounds.

Murray Horne, curator of visual arts at the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust and curator of this exhibit, has worked with Saluja for 25 years. Horne said the sheer number of Miniatures that Saluja has created — numbering in the hundreds — is impressive. Of the Miniatures that Saluja has created, 205 are currently on display in the exhibit.

“You don’t see as much [mandala] because they’re harder to produce,” Horne said. “Miniatures let’s you make your own associations — your eye is able to take you for a walk, so to speak.”

Horne said the small size of the Miniatures also allows viewers to connect to the pieces more deeply, which cannot be done with larger pieces. They’re also more affordable than their larger pieces of art — the Miniatures cost $85 for an individual unframed work, and the framed works range from $100 to $800 a piece.

“I want to show small intimate work, especially from those who have a consistent body of work that’s thematically linked,” Horne said. “You would not see these paintings elsewhere in this format — one of the ideas is that someone can just walk in and buy one of these works.”

Saluja conducts his art and his life with respect and kindness, but doesn’t let that limit him. He believes in the concept of “chaos with limitation,” or more simply freedom within boundaries. Improvisation forms the philosophy of his art, and through that he finds his freedom.

“I have a general idea of what a mandala looks like — then I take off,” Saluja said. “Instead of creating beautiful patterns, I’m just going crazy.”

In a previous version of the story, The Pitt News mistakenly reported that Saluja is 60 years old. Saluja is actually 70 years old. The story has been updated to reflect the correct information. The Pitt News regrets this error.