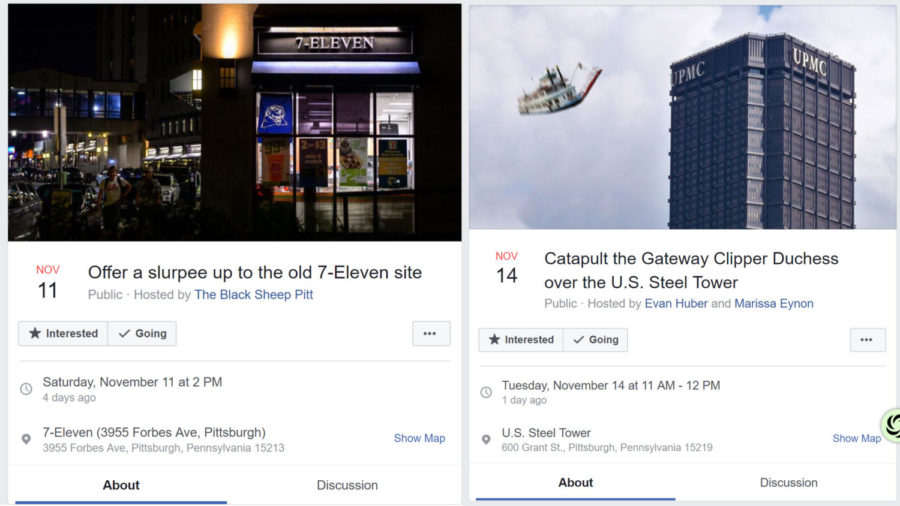

I showed up to the Facebook event, “Offer a Slurpee Up to the Old 7-Eleven Site,” Nov. 11 in the hope of finding the 360 people who said they were interested in attending — but I was the only one there.

No one offered Slurpees in an attempt to magically bring back the storefront. What once was 7-Eleven is now a holiday pop-up for one of the University-associated stores and a display of high-end stainless steel water bottles stands in place of the former Slurpee machine.

Facebook events are an easy way for users to invite people to parties and gatherings or for organizations to promote the functions they coordinate. But since 2015, joke Facebook events — from “Catapult the Gateway Clipper Duchess over the U.S. Steel Tower” to “Drain the rivers to build more bike lanes” — have also flooded students’ news feeds, walking the line between harmless meme and fake news.

Deborah Lee, a senior design and human computer interaction major at Carnegie Mellon University, was scrolling through Facebook one night when someone posed a question in a CMU meme page, asking why there were fake Facebook events for Pitt but none for CMU.

Lee — known in her friend group for her Photoshop prowess and love of memes — decided to fill the void by creating “Naruto-run up walking to the sky,” a fake Facebook event encouraging students to sprint up Jonathan Borofsky’s sculpture with their arms behind their backs, mimicking the signature ninja run from the popular Japanese anime “Naruto.”

“In four minutes I made this whole thing up, and picked a random date, and chose ‘Walking to the Sky’ since it’s one of the most iconic things about the campus,” she said. “I just wanted to make something really stupid and ridiculous.”

Lee said she wasn’t surprised with her motivation to create the event, but that she wasn’t expecting it to receive such a strong response. More than 1,000 people — including Pitt, CMU and Point Park University students — marked themselves as interested in the event. And 301 people said they were attending.

“When I posted it as a reply to the person who asked about it, they were like, ‘This is exactly what we need,’ and it got pinned to the page,” she said. “I think that’s the reason why so many people saw it.”

Although no one attended Lee’s fake event, people showed up for fake events in other cities. For an event titled “Scream Like Goku In Front of Washington Square Arch” in New York City, a handful of people gathered near the monument and mimicked the popular “Dragon Ball Z” character’s battle cry for more than an hour.

In Pittsburgh, people dressed up as Shrek — from the popular 2001 movie of the same name — at a free Smash Mouth concert in August after a Craigslist ad was turned into an event.

Paula Lockwood, a 25-year-old Lawrenceville resident, attended the concert with a friend and made their own Shrek costumes — complete with brown vest, green makeup and his signature ears — after noticing the event on Facebook.

“I thought it was too funny to be true, and my friend was like, ‘We should do it,’” she said.

Although these joke Facebook events could be considered fake news — both proliferate information that’s false — Lockwood said there’s a substantial difference between the two. According to her, one is made for fun, and the other has actual consequences if taken as the truth.

“It’s a funny, relatable thing that I share with my friends, and it’s like tagging someone in a meme,” she said. “Except it’s a Facebook event.”

According to Meredith Guthrie, a professor and adviser in Pitt’s Department of Communication, people have always used traditional media in nontraditional ways. Dadaists used absurdist art to criticize logic, reason and aestheticism of capitalist society in the 20th century. However, thanks to the internet age, more people have more tools — like photo and video editing software — to break with convention, according to Guthrie.

“I think that digital media makes [breaking conventions] even easier, because it means that everyone can potentially become a media producer,” she said.

But easy access has its consequences. Although Facebook has regulations put in place for curbing racist or inappropriate events — users can report these events if they pop up on their news feeds — Guthrie says Facebook is uneven in how they respond to this, and the event isn’t guaranteed to be removed if it’s reported.

Take Twitter, for example — the site temporarily suspended actress Rose McGowan for posting a private phone number, but allowed President Donald Trump to keep his account despite multiple complaints about him violating the site’s terms of services.

Social media sites and their users, according to Guthrie, face a dilemma when determining what to ban and what to keep.

“On the one hand, we don’t want to overregulate and create a culture of corporate censorship, while on the other, we don’t want social media to become a megaphone for hate,” she said.

Facebook is currently tweaking its algorithm to fight the spread of fake news, making it harder for people to share articles about events that aren’t real. But with no known protocol for moderation, bending the truth is as easy as hitting “create event” for fake Facebook event creators like Lee.

“They’re trying to figure out an algorithm to find news that’s not real. It might be harder to make the same thing for fake Facebook events,” she said.

Until Facebook creates an algorithm or the fake events turn nefarious, Lee said people will keep creating and “attending” them to take part in the internet’s newest meme.

“You’re just saying that you’re going because you want everyone on Facebook to see it and say, ‘Oh wow, that person is so ridiculous,’” she said. “You’re not clicking on a fake event for yourself, but more to show your Facebook friends.”