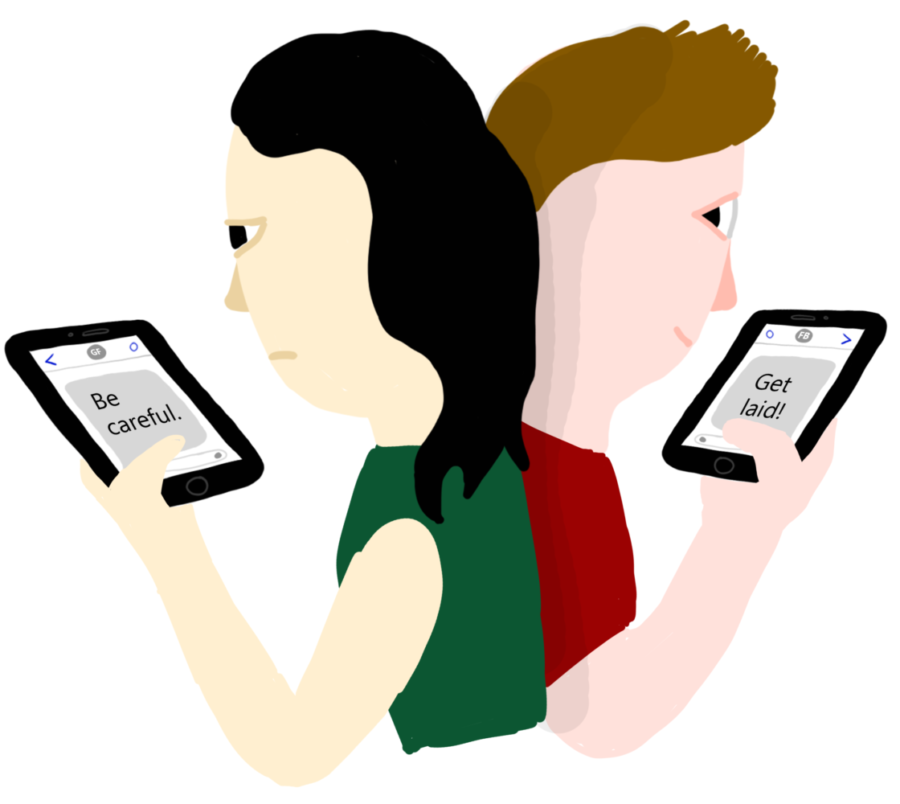

The infamous words of pre-college advice for girls at my high school graduation party were “never leave your drink unattended,” and, if you ignored that, “don’t drink the punch” — warnings against the dangers of college parties, particularly when alcohol is involved.

These are valid tips, considering one in five women are sexually assaulted while in college, according to a 2010 study by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. But when my family had that conversation with me, I was confused. I had never heard anyone tell their son, nephew or grandson to “remember not to sexually violate anyone” or “don’t drug anyone’s drink.”

Today, the conversation surrounding sexual assault is far different. Largely stemming from widespread accusations against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, whom 83 women have accused of sexual assault or harassment since early October, the conversation is now commonplace at a dinner table. But this discussion is more nuanced than ever, and it’s crucial to understand the way language organizes culture — and how we can use language to work toward solutions.

In a recent viral Twitter movement, Alyssa Milano, an American actress and singer, encouraged hundreds of thousands to speak up by using the hashtag #MeToo to indicate being a survivor of sexual assault or harassment.

While the hashtag went viral, another conversation did too — prompted by a 2012 TED Talk by Jackson Katz, an academic and filmmaker who focuses on issues of masculinity. The title of the talk was “Violence against women — it’s a men’s issue,” and the topic was rhetoric — specifically, how passive language propagates the belief that sexual assault is inherently a women’s issue.

“A lot of men tend to hear the term ‘women’s issues’ and we tend to tune it out,” he said. “It gives men an excuse not to pay attention.”

And while the effort of the #MeToo movement was to bring the conversation to everyone, it inherently makes sexual assault a women’s issue the same way Katz argues passive language does. Not only is it inaccurate, but making sexual assault just a women’s issue fails to address the root of the problem — a much more deeply seated cultural acceptance of sexual harassment and assault.

I even heard evidence of it on my local radio station 94.5 WPST when I was in New Jersey for Thanksgiving break. I jumped in my car and the first song that came on was a bit outdated, but upbeat and familiar. It wasn’t until I started listening to the actual words that I realized the song from my childhood was a small contribution to the encouragement of sexual misconduct.

“Something ‘bout your body says, ‘Come and take me,’” I heard Enrique Iglesias sing in his hit song, “Bailando.”

This line played in my head repeatedly, all through the holiday. Without the use of blatant derogatory language, the song still manages to assert it’s okay to infer consent from clothing — the first step in victim blaming. This is just one example of the media and entertainment industry promoting harassment and assault on a daily basis without people even being aware of the message it’s sending.

The public even seemed shocked when Louis C.K. became a part of the chain of sexual violators — a man who literally built his career on jokes about masturbation and child molestation.

His new comedy “I Love You Daddy” was scheduled to be released next week before it’s abrupt cancellation amid these recent allegations. It was supposed to feature a man masturbating in front of other women who failed to report the misconduct — ironic, considering his alleged actions with two women in a hotel room 10 years earlier tell a similar story.

But joking about sexual assault only contribute to a culture that accepts this behavior and brushes off its victims. If people are willing to laugh at jokes of sexual assault, nothing will force harassers to realize assault is no laughing matter.

So while the current movement, including the #MeToo hashtag, is a positive step forward, we need to be more proactive. We must try to change culture from the bottom up by rejecting casual sexism and holding abusers accountable. We must do as Katz calls for and redefine the ways we talk about sexual assault.

And survivors themselves are also calling for this. Leeann Tweeden was allegedly sexually harassed by Democratic Sen. Al Franken of Minnesota in 2006 while she was serving for the United Service Organization supporting American troops. Franken pretended to grope her breasts while she was sleeping, and had an onlooker take a photo. She also alleges he kissed her without her consent — and in an interview with CNN, she spoke about how society can do better.

“That’s really where the change is going to be driven from,” she said, referring to our cultural acceptance of assault. “Not from the victims coming out and talking about it. I think it’s going to come from the people who maybe do the abusing, that don’t even realize they’re doing the abusing, because it’s so a part of the culture.”

Bringing women’s voices to the forefront of the conversation the way the #MeToo movement does is important — but even more necessary is holding the men who create such a toxic culture accountable. And if we want to move society toward that, we must start with changing the language we use to talk about sexual assault to show that sexual assault is not just a women’s issue — it affects us all.

Ana primarily writes about culture and social issues. Write to Ana at aea51@pitt.edu.