Last weekend you could probably find Leonardo Solano buried in the dissertation room of Hillman, or pocketed away somewhere in Panera Bread, grading 160 pages of undergraduate Spanish papers.

While it usually takes graduate students such as Solano a long time to grade papers during the semester, finals is an especially grueling time that involves late nights, little sleep and plummeting diets.

“That’s why [grad students] get fat, they work so much just grading,” Solano, a fourth-year Hispanic languages and literature grad student said.

The stress of finals isn’t just felt by students, but by professors too. Each exam taken or paper submitted translates to a document a professor or teaching assistant must grade. Once finals week is over for students, professors are still working into the first few days of break to complete their part.

According to Solano, the Hispanic Languages and Literatures department uses a detailed evaluation sheet that advises instructors about how to assess content, sentence grammar, style and transitions to make grading more objective. Solano supplements these standardized methods with his own requirement for students to write five drafts of their work and then meet with him throughout the semester to talk about the pieces.

“For me it’s an ongoing process,” he said. “The better professor you want to be, the more time you want to spend.”

Solano said grading just one paper can take up to an hour because he spends time on both grammar and content and frequently rereads his students’ work.

“It depends on the flow, it depends on the student,” he said. “Every student is different and has different needs.”

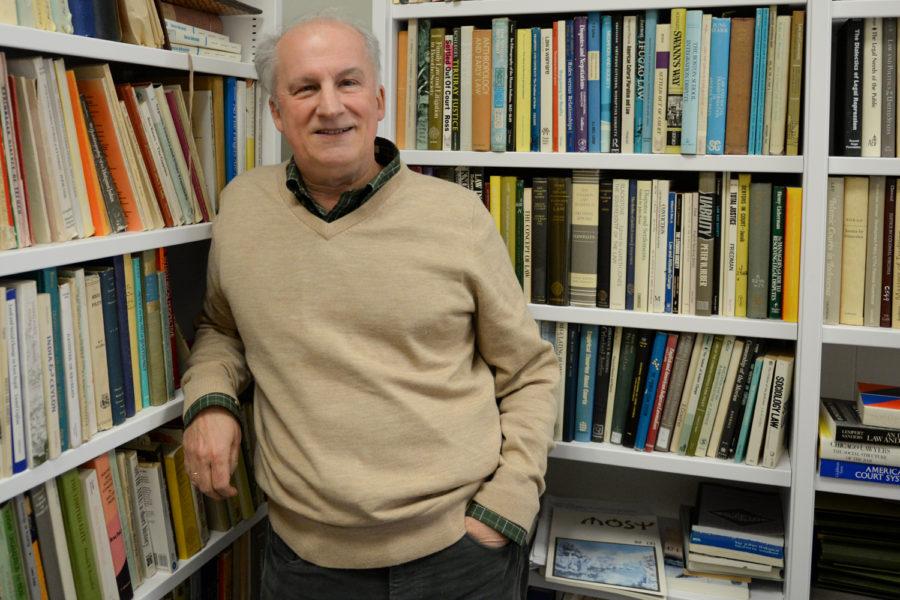

Robert Hayden, an anthropology professor who has taught at Pitt for 31 years, frequently spends more than an hour grading each term paper produced by the 20 students in his ethno-national violence writing-intensive course. He edits for grammatical errors, but he focuses the majority of his efforts on the papers’ content.

“I’m much more concerned with how the paper is conceptualized and with how the ideas are playing out, how they’re supported or not supported,” Hayden said.

After his students submit their drafts, Hayden returns them, loaded with edits, accompanied by a summary document that contains general comments about the paper.

“It’s a lot of work to go through [all the papers], but you know, a W-course to me, I mean that’s what I’m supposed to be doing,” Hayden said. “From my point of view, the exercise is a high level of writing.”

Aside from the 20-page paper that is the focus of Hayden’s ethno-national violence class, students must also take two-to-three exams throughout the semester. Each exam allows students to select two essay questions from three, four or five choices.

Hayden, who also teaches cultures and societies of India, has developed a system for grading these exams. He separates the responses to each essay question into piles. He reads through the answers for one question and puts comments on each answer before moving on to the next question. He rereads the answers, ordering them from best to “least best” before rereading them a third time and assigning final grades. The process, for a class of 40 such as cultures and societies of India, takes several days.

“How I have to grade the exams is taking into account what people are demonstrating that they’ve learned. And that takes repeated readings,” Hayden said. “And that takes a lot of time.”

Like Hayden, Solano said the extensive notes and constructive criticism he offers his students takes the most time.

“I hate to read the feedback. It’s like torture, a really painful process because you don’t want to see the mistakes,” he said. “But I learned that we need to get used to that.”

Solano said he invests this sort of time while still cognizant of his own demands as a grad student in the final stages of writing his dissertation. Despite his attempts to spread his papers out over a longer period of time, Solano said grad students sometimes must sacrifice the time put into grading finals to budget time for their own work.

“You cannot pay attention as much as you want especially during finals,” he said. “You cannot be as detailed as you want as you do it throughout the semester.”

For Birney Young, a public speaking instructor at Pitt, finals season lacks the usual piles of papers and scantrons. Instead, his final exams are performance-based impromptu speeches, which students do not know the topic of until moments before their speech.

“Usually there’s a common thread of things I’m grading for in all the speeches in public speaking,” he said. “Whether they’re able to speak without fidgeting, good eye contact, vocal variety and use of good transitions.”

Though most have grown comfortable with public speaking by the end of the semester, Young said the pressure to perform a final speech in seven minutes has proved particularly difficult for some students. He recalled one student who broke into a cold sweat, freezing up two minutes into his speech before classmates shouted out questions related to his topic to prompt him to continue.

“I don’t get any credit for that, that was just an awesome class and they helped him through it,” Young said. “He was able to finish the speech because the class collaborated together to throw him assistance whenever he needed it.”

Young has also been an instructor for an argument class as well as a teaching assistant for rhetorical process. In grading papers for those classes, Young said he gives extra credit when a student includes a pun in their assignment — but only if it works well within the context of the paper.

“You’re still doing a good paper and on top of that you’re putting in the extra work to make my life happier,” he said. “Why wouldn’t I give extra credit for that?”

While Hayden doesn’t reward students for inserting puns in their assignments, his commitment to grading comes down to the effort his students put into the class and the assignments.

“I’ve asked students to write pages, paragraphs on complex topics,” he said. “I’m going to invest the time to read those.”