You’re a young person, freshly starting your career and beginning to make a name for yourself. You are entrusted with big tasks, like handling confidential material, managing the business’ account and leading the new public relations campaign.

Now, imagine that, like an unfortunate mirror of your own accomplishments, your sexual assaulter is allowed the same responsibilities — maybe an office a branch away or a county away. Maybe their tasks are even bigger than your own. Even though they acted in a terrible way, their privilege is just as strong as before, and the cycle of assault will likely continue. It hardly seems fair.

Across the news, countless stories from sexual assault survivors have finally begun to surface, such as those of U.S. Olympic gymnasts like Simone Biles and Gabby Douglas and actresses like Gwyneth Paltrow and Angelina Jolie.

Although the survivors undoubtedly deserve to speak the truth, this coverage can cause the media to ignore the bystanders behind the scenes — the bosses. These are the supervisors who knew and did nothing or took minimal action to protect accusers and punish the accused.

There may not be a solution to sexual assault, but one important step is evident — people in charge must start taking more drastic measures to punish offenders. Only then will the enabling culture for sexual assault finally begin to change.

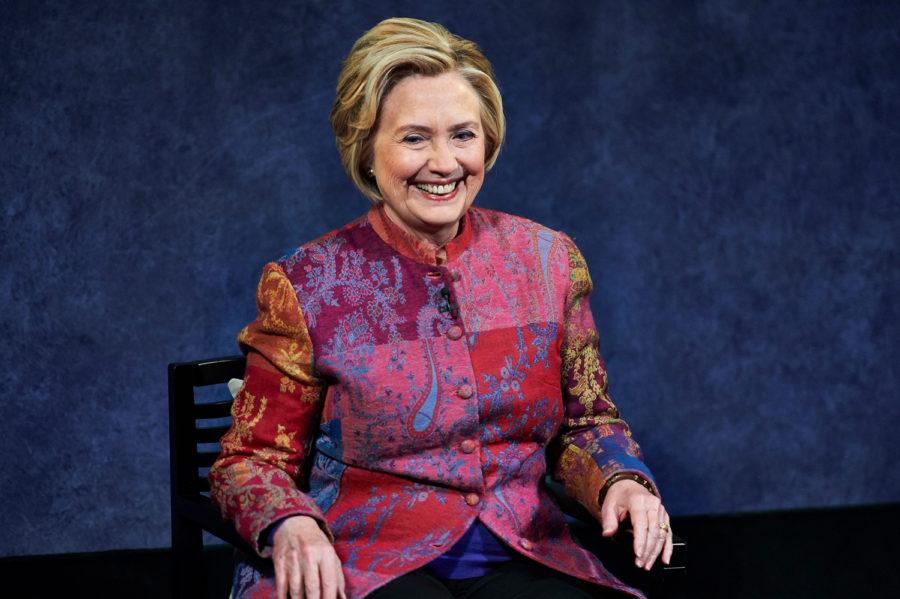

Earlier this month, an article in The New York Times revealed Hillary Clinton protected senior adviser Burns Strider, who was accused of sexually harassing a woman on Clinton’s team during her 2008 presidential campaign.

Clinton was aware of the harassment, and her campaign manager even advised that she fire Strider. Instead, Clinton simply moved the woman to a new job within the campaign, docked Strider’s pay and sent him to counseling — only to fire him months later after additional misconduct allegations.

Clinton’s response to the accusation is inexcusable. As a candidate who claimed to stand for the rights of women, she refused to stand up for her female staffer in this situation — instead doing only what suited her own individual success.

And this issue isn’t limited to the political sphere. Radio DJ David Mueller, who groped Taylor Swift in 2013, now has a shiny new gig at Mississippi radio station Delta Radio.

Mueller was fired from his old DJ job in Denver after Swift said Mueller grabbed her butt during a meet and greet session. Mueller sued Swift for losing his job, and she countersued for just $1. A judge threw out Mueller’s lawsuit, and a jury found him guilty of battery and assault.

Now, not even a year after Swift reigned triumphant in the lawsuit, the Mississippi station picked up Mueller to give him a fresh, undeserved start. And his new employer doesn’t seem to care about the reality of his past.

The head executive of Delta Radio, Larry Fuss, received swathes of angry emails protesting the new hire — and his response was anything but respectful to Swift or the nature of sexual assault in general.

“There is no hard evidence that Mr. Mueller is a ‘sexual predator,’” Fuss said. “Attempting to crucify the man for what was, even if he did do it, not on the same level as an actual sexual assault, is out of line.”

Fuss’s response is almost ironic, and clearly way more out of line than punishing a man for inappropriate touching — which, by the way, is “actual” sexual assault. RAINN, an anti-sexual violence organization, includes unwanted sexual touching in the definition of “assault.”

He even denies Mueller ever groped Swift, although a damning photo of Mueller’s hand uncomfortably behind Swift with the singer awkwardly leaning as far as possible in the other direction is available with a quick Google search.

Fuss giving Mueller a second chance is one thing. Even though it is irresponsible in light of the recent court case and the #MeToo movement, it is at least comprehensible. Fuss’s denial, however, of Swift’s assault is despicable.

Denying a harassment case that was actually proven in a trial has consequences beyond the case in question. If a harassment incident occurred at the Mississippi station, it would be much more difficult for the survivor to come forward — especially if the culprit were Mueller.

If Fuss did not believe an assault proven in a court of law, why would he believe an assault reported to him by his employees?

The commonality between Clinton’s and Fuss’ cases is the inability of two superiors to take into account the widespread repercussions of harassers’ actions. Both employers’ actions were problematic — in Clinton’s case, dismissing the seriousness of assault, and in Fuss’ case, denying that they ever happened.

In a 2017 Pew Research Center poll, 22 percent of employed women said they had experienced sexual assault at work. It is time for bosses to step up and take charge of their employees by refusing to brush these statistics and stories aside. If an employee is accused of harassment, the conversation should not end with the accused and the superior.

Supervisors need to actively engage in conversations with employees about what is considered harassment — and not only listen to them, but take strong action when workers come forward with harassment or assault claims.

Changing the workplace culture will, in turn, help to create an environment where employees know they cannot get away with abuse.

But nothing will change unless those around the survivors begin to speak out as well, especially when it comes to workplace superiors.

Alexis primarily writes about local issues and student life for The Pitt News. Write to Alexis at alb413@pitt.edu.