There is currently no statue in Pittsburgh that represents an African-American woman. But that is going to change in the next month — and it’s happening right on Pitt’s campus.

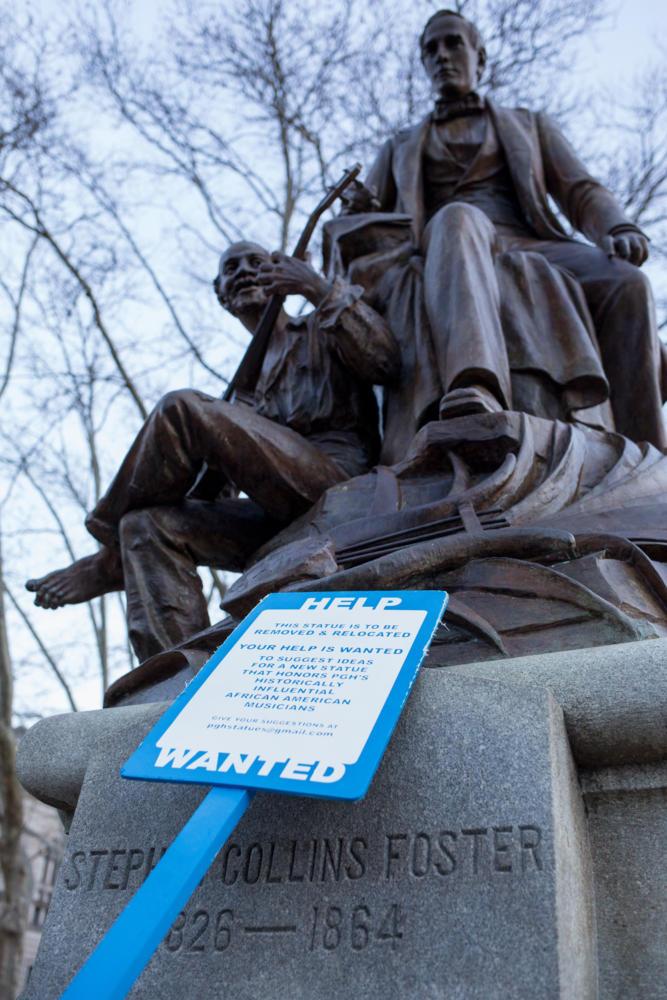

The City confirmed in March that the 10-foot-tall bronze statue of musician Stephen Foster, located on Forbes Avenue across from the Stephen Foster Memorial, would be removed in April. Foster will be replaced with a local, historical, female African-American figure. The City has called for community input on deciding who the new figure should be.

Though the statue is in Oakland, the first of those community meetings took place across the City Tuesday night at the McKinley Recreation Center in Beltzhoover. Only five members of the Pittsburgh community joined the City’s Task Force on Women in Public Art at the first of five chances for community input.

“I feel like art should represent everyone,” Beltzhoover resident Margie Thompson said. “This is how we learn about each other.”

The goal of these forums is to understand what values and priorities are important to the community when it comes to the design and artist of the represented African-American historical figure.

Lindsay Powell, a policy analyst in Mayor Bill Peduto’s office and member of the task force, opened up the forum with a background information on the project. But most of the community members were unaware about the specifics of the topic being discussed in the meeting. They had not heard much about the City’s new project and came to become more informed about the African-American women who were being considered to replace the Foster statue.

Foster is famous for crafting songs such as “Uncle Ned,” “Oh! Susanna” and ”My Old Kentucky Home.” He was known during his time as a writer and performer of African-American minstrel music — music inspired by black culture and often performed in blackface in theaters.

But, as shown in the second verse of “Oh! Susanna,” Foster’s music continued to affirm the racial prejudices and discrimination of African-Americans.

Powell said the City finds it important to celebrate the legacies of black women. They have created online surveys and will provide other forms in other communities including Homewood and the Hill District. According to Powell, the online survey has already produced 1,000 different responses.

“It was really important to us and the mayor to go to communities and talk about what ideas and concerns they had,” Powell said. “We wanted to know what they [the communities] wanted us to consider in replacing the statue.”

Currently, the Task Force on Women in Public Art — a group of local women selected by the City for their work with women and art — has researched African-American women they feel are fit to replace the statue. The biographies of the women are currently on display around the statue.

Women such as Gwendolyn J. Elliott, who was part of the first group of women hired to be Pittsburgh police officers, and Helen Faison, a graduate of Pitt and the first black female high school principal in Pittsburgh, are in the running. The other women the City is considering include abolitionist Catherine Delany, millionaire entrepreneur Madam CJ Walker, educator Dr. Jean Hamilton Walls, singer Mary Cardwell Dawson and artist Selma Burke.

Tim Dawson, cofounder of advocacy group The Art of Democracy, served as the facilitator of the discussion. After allowing community members to introduce themselves, he encouraged the five members in attendance to describe important values that the task force and the Pittsburgh Art Commission should emphasize in the project proposal.

Steven McCray, 63, drove in from Meadville for the forum. He felt like it was important to choose a woman who would represent values of community involvement and insight.

“We all know about history, but we never really learn about ‘her-story,’” he said.

Members of the community got an opportunity talk about what visions they had for the new statue. Many of them used personal experiences as a way of incorporating their thoughts and ideas in a creative way.

Thompson has collected dolls for most of her life. Inspired by the skirts of the dolls, she brought up the idea of having multiple African-American women featured instead of one.

“I thought of a figure that represented all African-American women,” she said. “Like how the skirt opens of the doll’s dress, you could have their faces represented [in the fabric] or around the statue of the unidentified statue of the black woman.”

Beltzhoover residents like Jill Evans, 60, were curious as to how the African-American women in the running were chosen.

“There are no more black women who are well-known except these women? Is that what we are saying?” she asked.

The City is open to ideas outside of the seven women the task force picked. The City’s survey has a spot for residents to submit additional names of influential black women.

Ideas about art, design and representation took up the majority of the discussion. But the members of the community felt that it was important in incorporate other groups in the community, such as younger generations, into the decision-making process. Community members felt like the City would be missing an entire demographic by only using the internet as a source to get information from the community.

“Not everybody has access to internet,” Thompson said.

The group suggested putting out information in newspapers with a number to respond to as well as sending out mailings. They also agreed it could be beneficial to visit the places in the community, such as churches, where members gather.

The next forum will be held April 19 at the Pittsburgh Project where members of the community and the City’s task force will meet again to discuss who will replace the Stephen Foster Statue.

“It takes a very strong woman — you have to have to have that internal strength to go forward with what you believe — to get things done,” Thompson said. “These women have done things and there are many others who have done such that.”