State should step up to address rising tuition

August 20, 2018

As a rising junior at the University of Pittsburgh, I only have two more years until I graduate and enter the workforce, armed with an English Writing degree and a list of recommendations — and saddled with tens of thousands of dollars in student loans.

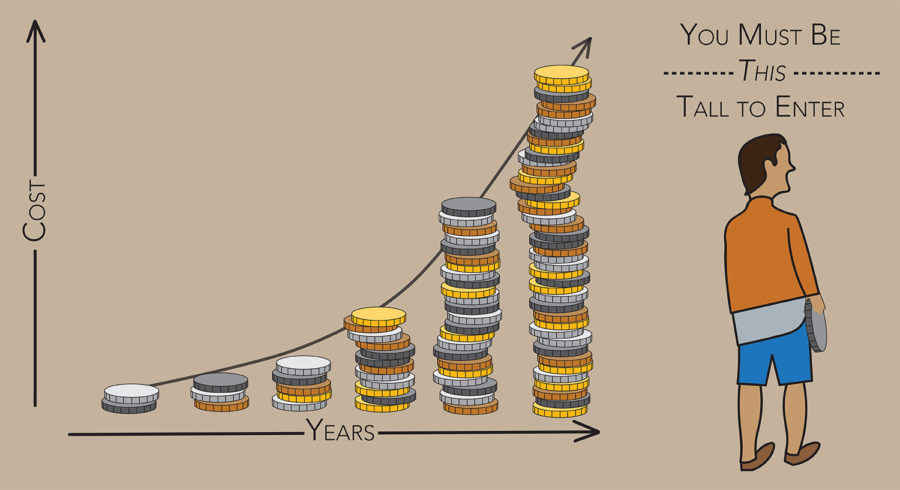

At an average of $12,186 for in-state and $ 24,312 for out-of-state, Pennsylvania colleges have some of the highest average tuition rates in the country — Pitt’s rests at $18,192 for in-state students like myself, making it the second-most expensive public school for in-state residents in Pennsylvania. And this doesn’t even include the costs for room, board and other fees. But instead of taking action to address the roots of the state’s student debt crisis, the state responded by introducing a new program that encourages families to prepare for when they fall victim to it.

The new Keystone Scholars program, effective beginning in 2019, will give every child who is a Pennsylvania resident at birth — or adopted by a family in the commonwealth — a $100 grant toward their college savings. The investment could grow to roughly $200 by the time the child turns 18 and about $400 by age 29, the maximum age a person can use the grant under the program. This small amount is meant to encourage parents to start saving their own cash to cover the cost of college.

This ultimately helps little. Pennsylvania students graduating from public and nonprofit colleges in 2015 left their alma maters saddled with an average of $33,264 in student loan debt — several thousand more than the national average of $28,950. This is a cost no one family can reasonably take up on their own, but that many have been forced to due to the state’s refusal to intercede. And that may prove fatal for the state’s economy, unless the government starts providing solutions that take the stress off its citizens.

It’s unclear why tuition rises every year. Some claim it’s because public and private colleges and universities have been expanding their payrolls – the number of administrative positions reportedly increased by 60 percent across the United States between 1993 and 2009. Others cite costly but necessary efforts to attract more applicants by introducing more amenities and constructing new buildings.

Still, student loan debt wasn’t considered a real crisis until it spiked significantly during the 2008 Great Recession — according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the country’s total student loan debt nearly doubled between 2008 and 2013.

Other research, like that found in the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities report “A Lost Decade in Higher Education Funding,” points to budget cuts in state funding for public higher education and shrinking government subsidies for private schools following the 2008 crisis as the main reason why students need to shoulder so much of the cost on their own. Despite the global impact of the 2008 crisis, the United States was one of only five members of the worldwide Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to cut public spending on education.

Sara Hebel and Jeffrey J. Selingo, editors at The Chronicle of Higher Education, also cite a shift following the 2008 crisis in how politicians and lawmakers view higher education. In recent years, more have come to see it as a private privilege paid for by individuals rather than a public good that needs state support.

“Politicians who are generally sympathetic to higher education haven’t been much help,” Hebel said in her 2014 piece, “From Public Good to Private Good.” “When budgets have been tight, they have first protected other priorities — prisons, roads, elementary and secondary schools.”

The wounds the crisis left may be healing, yet tuition keeps going up and state funding is not rising fast enough. Combining these factors with stagnant wages and the increasing necessity of a college degree means that Pennsylvania graduates will face decades of putting a significant part of their paycheck toward student loans.

Pennsylvania’s government cannot sit idly by while students are financially drained by the cost of being students — this is only going to hurt the state later. Today’s graduates are tomorrow’s workforce and consumer base. Impoverishing them will ultimately impoverish the state and likely lead to Pennsylvania natives seeking opportunities elsewhere.

States with a robust education system through government assistance tend to have thriving economies with opportunities for advancement, according to a US News report. If college costs keep going up, fewer people will be able to afford to attend, hindering their advancement to better-paying jobs or careers that require extensive training.

This forces graduates to put their cash toward their loans instead of pouring it into other markets. Fewer people are buying homes, cars and starting small businesses, Barbara O’Neill, a specialist in financial resource management for Rutgers University, told Business Insider.

“A lot of things are being postponed. You got what you call a crowding-out effect — people only have so much money,” she said. “There’s a lot of business activity that isn’t taking place … It’s a drag on everything.”

But the state isn’t helping the Pennsylvania college system much. State-related campuses as such as Pitt were initially flat-funded in Gov. Tom Wolf’s proposed budget for 2018 before being bumped up to 3 percent. And arguing about this and other moves by the government lasted up until the budget was finally passed 10 days before the fiscal year ended. Now Pitt’s graduate and out-of-state undergraduate students are facing a tuition hike for next year and decisions about the 2019-20 fiscal year are looming.

If a college is becoming more of a necessity for the economic wellbeing of its citizens, then the state must make investing in college funding a priority. Instead of introducing more initiatives like the Keystone State Program that put the responsibility of paying for college on students and their families, the commonwealth could ease their burden by raising revenue to put toward higher education. It could achieve this by repealing ineffective tax deductions, exemptions and credits or by rolling back shortsighted tax cuts.

In addition to helping shoulder the cost of tuition, the commonwealth also should make the process of paying off student debt easier by supporting payment plans that do not immediately put stress on a person’s earnings. Pushing for an income-contingent repayment system like the U.K.’s, where the state requires that repayment doesn’t start until income exceeds $25,977 and that payments rise and fall with income, would be a good start.

Tuition in Pennsylvania is rising more and more each year. Unless the state steps in with an impactful plan to help cover the cost tuition and ensure its future workforce doesn’t drown under a mountain of debt, students like me may end up fleeing elsewhere for their education and careers.