Japanese history evoked in new documentary from local filmmaker

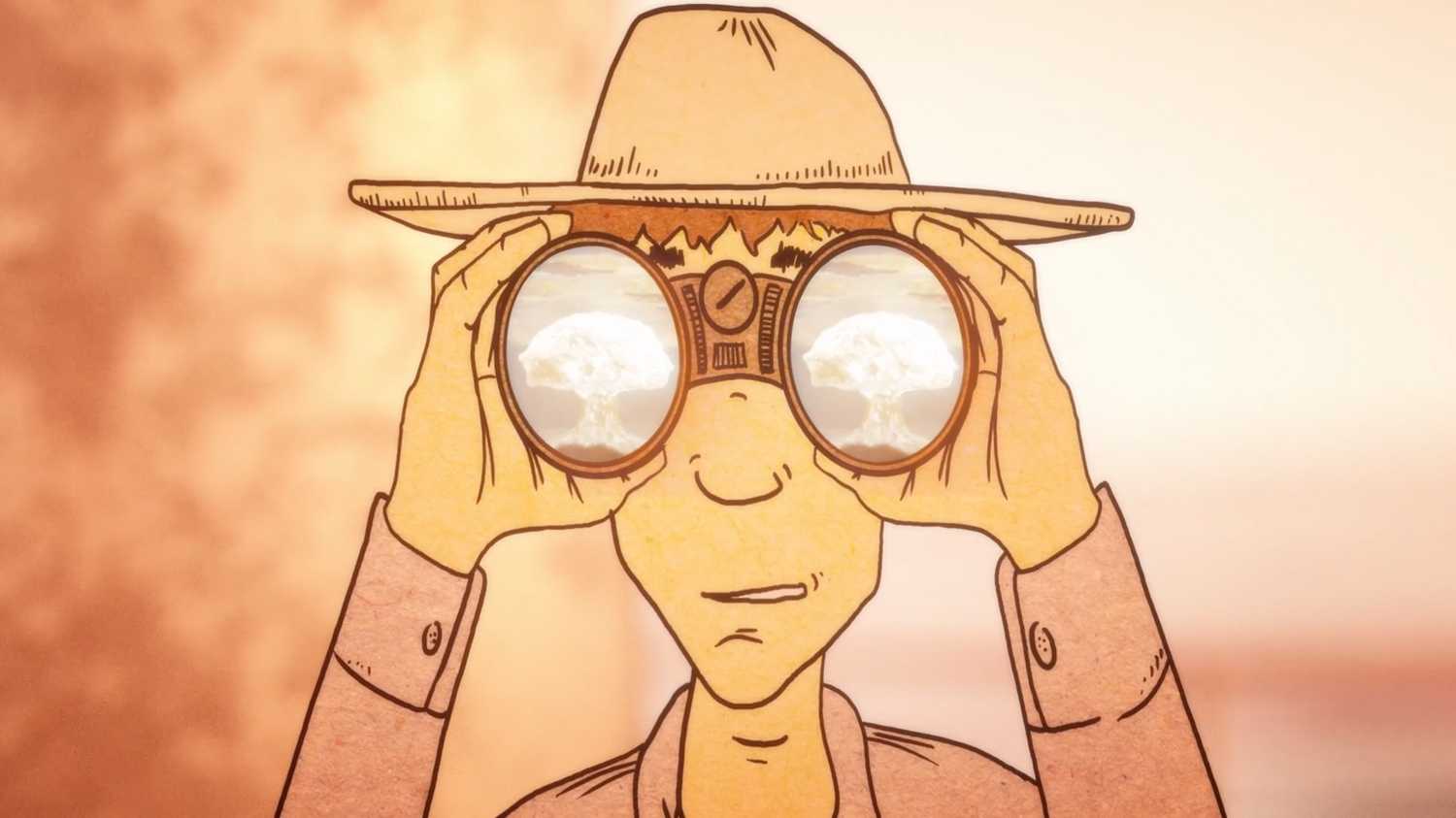

Screenshot via “Day of the Western Sunrise” Vimeo trailer

Director Keith Reimink’s documentary — about the personal fallout of a U.S. nuclear test on March 1, 1954 — premiered at Row House Cinema over the weekend.

October 2, 2018

For 23 Japanese fishermen, the sun rose in the west on March 1, 1954. An enormous cloud rose from the ocean near the Marshall Islands, filling the sky with light. The fishermen argued over what it could be, but the truth would ripple through the rest of their lives as pain, hospitalization and stigma. They were victims of the Castle Bravo nuclear test, the largest thermonuclear bomb the United States would ever detonate.

Japan’s relationship with nuclear weapons usually brings to mind events such as the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or even popular characters like Godzilla. But the damage of nuclear weapons extends much further and director Keith Reimink’s new documentary, “Day of the Western Sunrise,” focuses on the personal fallout. The film

premiered at Row House Cinema over the weekend, with a showing Saturday night and two on Sunday.

“It’s a small theater and kind of intimate,” Reimink said. “So rather than have one big screening, [we had] three smaller ones so people have more access to the film and the filmmakers and there’s a bit more laid-back feeling about it.”

Reimink stumbled upon the story of the 23 fishermen and their boat, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru — or Lucky Dragon No. 5 — in Eric Schlosser’s “Command and Control,” which investigates the mismanagement of U.S. nuclear weapons. Nestled among the 656 pages are 10 paragraphs about the Lucky Dragon No. 5, which Reimink honed in on as another story in its entirety.

Reimink began his research in early 2014, finding the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall in Tokyo, which features a reconstructed version of the fishing vessel. Producer Takako Kasuya helped set up and facilitate interviews with three of the six fishermen still alive at the time.

With the help of translator Akiko Ogawa, Reimink and his cousin Pete Bigelow sat down with each fisherman for two hours, but Reimink didn’t know the actual content of the interviews until subtitler Kanako Mhatre gave him the transcripts seven months later.

“It was a very difficult process in terms of interviewing,” Reimink said. “We had 30 to 40 questions and we just went down the list and crossed our fingers and hoped we got the answers we were looking for. Probably not the best way to make a film, but it worked for us.”

Reimink received Pittsburgh Foundation and Heinz Endowment grants to develop the project after returning to the United States. He brought on animator Josh Lopata, who created each character and moving item in the film. Lopata drew by hand in a style inspired by kamishibai, a traditional Japanese storytelling form popular during the Great Depression. For Reimink, it immediately felt like the right choice for the film.

“When we heard about this storytelling, we knew we had to use it. It just seemed to fit using a Japanese art form to tell the story,” Reimink said. “The film is entirely in Japanese. We kind of realized we needed the animation to be reminiscent of that. We did our best to stay true to that kind of storytelling method.”

To maintain the sole use of Japanese throughout the film, time and settings flash onto the screen in Japanese. Only the translator’s voice asks questions throughout the documentary and CMU visiting scholar Takaaki Matsumoto provides the narration. Matsumoto met Reimink through the Japanese Conversation Club at Carnegie Library and he was eager to help with the project.

“I met Keith and he was looking for a narrator and according to him, he liked my voice,” Matsumoto said. “As a foreigner, I think I am still a little bit isolated, but through this work I could do something good in this society.”

Lopata also put Reimink in contact with designer Justin Nixon, who created the environment of the film based on photos Reimink took on his trip, old photos from the 1950s of Yaizu, Japan — the home port of the Lucky Dragon No. 5 — and a 1959 film about the incident.

Troy Reimink, Keith’s younger brother, created the score for the film, primarily using guitar and piano to help set the mood of each scene. Keith also worked with the National Consortium for Teaching About Asia and Pitt’s East Asian language and literature department and film studies department throughout the process.

Neither Nixon, Lopata nor Troy had seen the film before the premiere, since they wanted the experience of seeing it with full sound and audience. Green Mountain Energy and Film Pittsburgh sponsored the premiere, which made it possible for Keith to donate the ticket sales and $1-per-pour of beer during the premiere to the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall.

The premiere opened Saturday night at 7 with gift bags of Pocky and green tea waiting for viewers as they entered the theater. The screen went dark and narrator Matsumoto’s voice filled the theater as a movie opened with an animated scene of a woman stumbling through the hell-like remains of Nagasaki Aug. 9, 1945, after the United States dropped the second atomic bomb ever used in war. As the woman kneels before water, the frame pans away over the boat and the title card appears.

The film then skips to Yaizu’s port, nine years later, the water no longer red from reflecting flames. Instead, it’s peaceful, with the soothing sound of ocean and seagulls in the background. The three fishermen — Matashichi Oishi, Susumu Misaki and Masaho Ikeda — explain how they got involved in the fishing industry. The scenes are intimate, each in their homes with no one else in frame except in Misaki’s segments, where his wife sits to his left.

The film continues to alternate between animated flashbacks and filmed sections of the fishermen recounting their roles on the ship and their fear of working and living on the old, creaky boat. The fishermen faced stigma from their peers once they returned home and early deaths of other Lucky Dragon No. 5 fishermen and birth defects in their children were difficult to bear. The film closes with the three fishermen’s reflections on the incident and what they do as their remaining time on Earth winds down.

An illustrated recreation of the Castle Bravo nuclear test shows a fisherman watching the blast through binoculars in the trailer for the Japanese documentary “Day of the Western Sunrise.”

“I thought it was fantastic,” Dacin Kemmerer said. Her boyfriend is Keith’s brother-in-law and she was one of many family and friends who attended the premiere. “There were so many different depths to it. There was the historical part and an educational aspect, but you also got the personal connection with each of the characters, too.”

The educational part is important to Keith, who also created an educational tool kit for teachers who want to bring this story to their classrooms. Now that the premiere is over, he hopes to show it at film festivals and eventually bring it to Japan if they are interested. He is also involved with several international peace and educational organizations he hopes will let him screen the documentary around the world.

“I want to be a storyteller first,” Reimink said. “The fishermen [in the documentary] were very open to talking about it because there’s not much U.S.-led conversation about this. If people wish, they can teach the material in the film, which is cool because it gives the project a bit more longevity.”