EPA aims to triple pace of deregulation in coming year

Former Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt participates in a meeting with state and local officials regarding the Trump infrastructure plan on Feb. 12, 2018, at the White House in Washington, D.C. The EPA wants to quicken the pace of deregulations. (Chris Kleponis/CNP/Zuma Press/TNS)

October 18, 2018

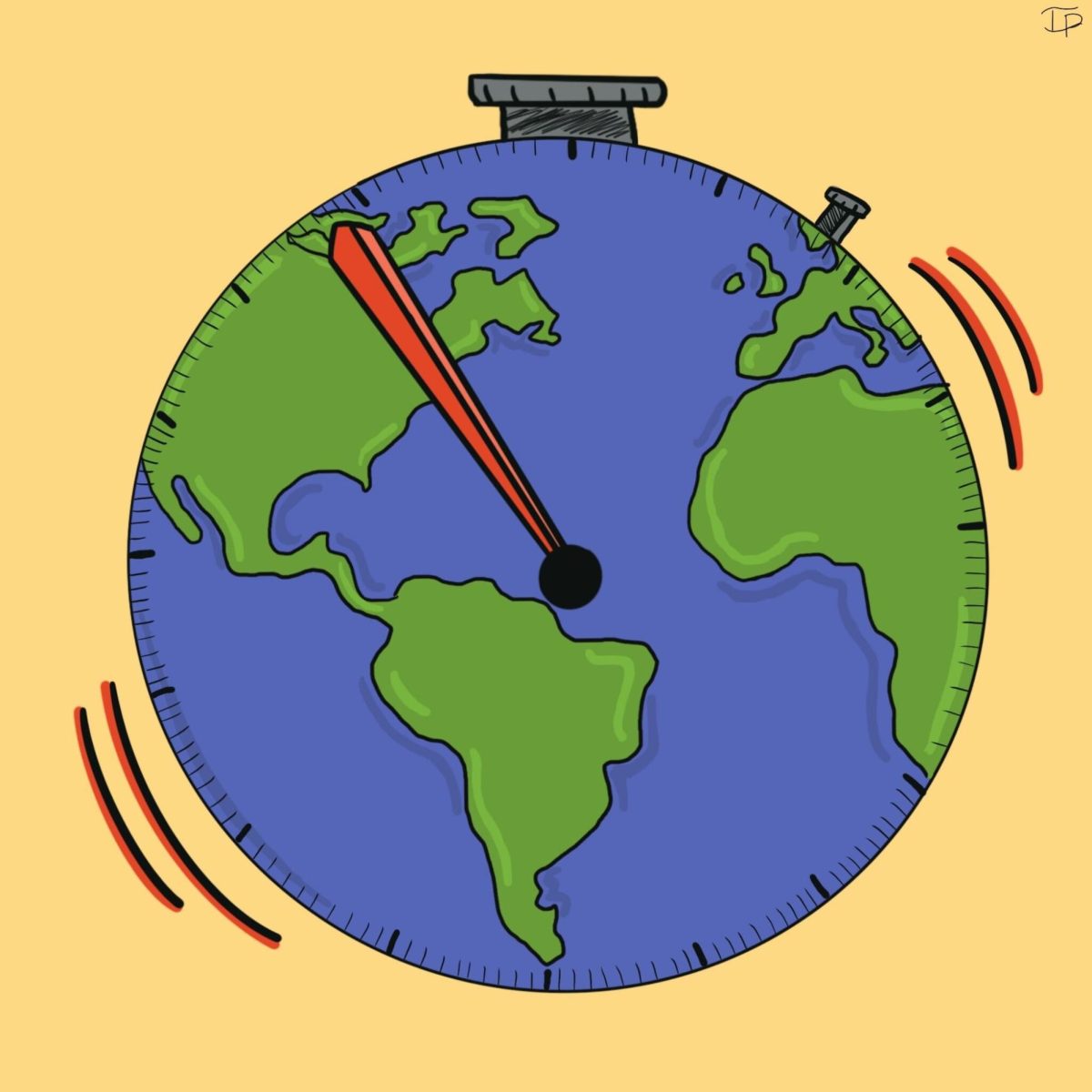

The Environmental Protection Agency released a plan for eliminating regulations next year that would likely dwarf its current rule-cutting pace.

The agency expects to finalize approximately 30 deregulatory actions and fewer than 10 regulatory actions in fiscal 2019, according to the Trump administration’s Unified Agenda, released Tuesday.

Such administrative speed would roughly triple the EPA’s pace from the prior year. In fiscal 2018, the agency finalized 10 deregulatory actions and three regulatory actions, resulting in an estimated $1.2 billion in cost savings, according to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

While the administration has argued that paring back regulations will reduce costs, many of the rollbacks have been soundly criticized by environmental groups for weakening public health protections and exacerbating climate change.

Under an April 2017 Office of Management and Budget directive, an action is considered “deregulatory” if its generates compliance savings for regulated industries, while “regulatory” actions generate compliance costs for the industries.

A potential “deregulatory” action heralded by OIRA is a proposed rule that the EPA and the Transportation Department issued in August that would freeze fuel economy and tailpipe emissions standards finalized under the Obama administration at 2020 levels through 2026, instead of enacting more stringent requirements. It would also revoke a waiver that allows California, along with 12 other states and the District of Columbia, to set tougher standards than federal levels.

In its review, the OIRA called the proposed rollback a “substantial” cost-cutter, citing administration estimates that it may save automakers $120 billion to $340 billion.

Also in the agenda, the administration projected that the EPA will finalize in March 2019 a proposal that would withdraw the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, which required states to draft plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions from existing coal-powered electricity sources and other generation sources.

Another possible rule to be finalized in 2019 is a revision of an Obama administration rule defining “Waters of the United States,” which, in an effort to clarify water protections, modified how the federal government determines which waterways are in its jurisdiction under the Clean Water Act.

The rule has been a point of consternation from congressional Republicans who consider it a government overreach. It has also become an issue in ongoing funding arguments. A GOP policy rider that would allow the EPA to withdraw the rule without statutory reviews has been a sticking point in recent Interior-Environment funding discussions due to opposition by Democrats.

Yet action on rescinding and replacing the WOTUS rule has been slower than anticipated. Then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt told a Senate panel in May that he expected a proposed withdrawal in the “third quarter” of 2018 and a replacement by year’s end.

Currently, the administration plans to replace the rule in two steps: a final replacement rule would be issued by March 2019, and a rule with its own definition of “Waters of the United States” would come by the following September.

In a move likely to assuage concerns among corn-state lawmakers about whether the U.S. will meet its statutory renewable fuel obligations, the agency said in the agenda that it will finalize by May 2019 a proposal to allow gasoline blended with up to 15 percent ethanol, known as E15, to be sold year-round. Sales of the 15 percent blend are currently banned in the summer months because of an EPA finding that it increases smog.