The tricks, treats and traditions of Halloween

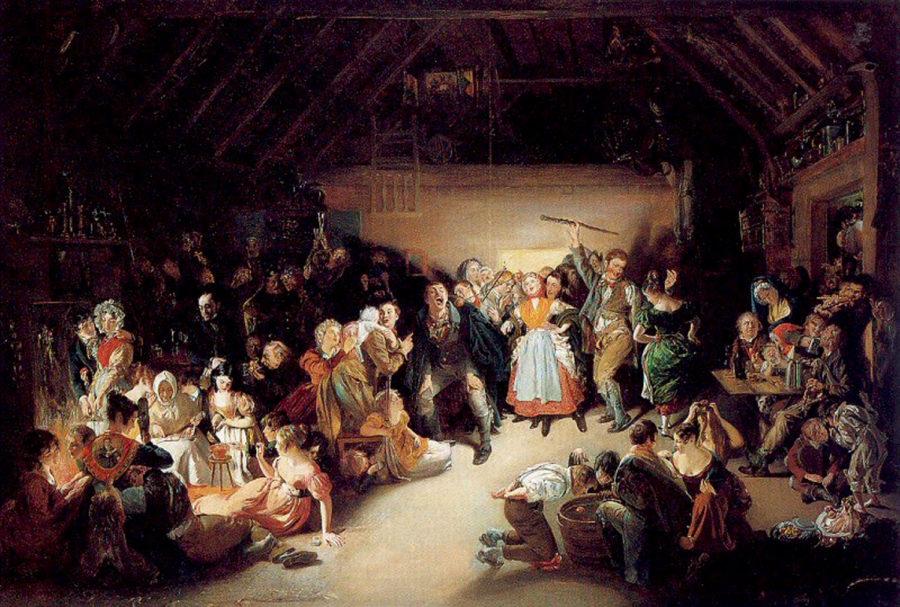

“Snap-Apple Night,” painted by Daniel Maclise, depicts divination games that would be played on Samhain.

October 31, 2018

It’s hard to believe that consuming mounds of Snickers and Kit Kat bars every Oct. 31 hasn’t always been a part of the Halloween tradition. In fact, the holiday used to be far from the hoarding of junk food, it was instead a time for rooting of kale and cabbage, and playing divination games.

Leslie Przybylek, the senior curator at the Senator John Heinz History Center, explained that the Halloween that exists in the United States today comes from a “shape-shifting” combination of traditions.

“The early holiday was really seen as a celebration of things like divination, especially [for] young men and women who could foretell who their love would be,” Przybylek said. “[People] would go hand-in-hand and walk into the garden and pull kale or cabbage and look at the root. If the roots were twisted or strayed or fat or skinny, those were things that predicted who your mate would be.”

She said scholars believe the holiday originates from the Celtic holiday of Samhain, which was a festival that marked the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter.

At the time, people believed the veil between the living and the dead was very thin, and eventually this festival merged with the Christian holidays of All Saints’ Day, a feast celebrated on Nov. 1 by Anglicans and Catholics, and All Souls’ Day, a time to pray for departed souls on Nov. 2.

Through the early 1800s in western Pennsylvania, Przybylek said the holiday was referred to as “Nutcrack Night,” which referred to a custom that predicted who a person would marry.

“You would put two nuts side by side by the fire and if one, as it burned, popped away from the other, it meant that the couple was not bound to be together, but if both nuts sat there and burned together gradually, it meant that you would have a long and enduring love,” Przybylek said.

Elizabeth Archibald, a visiting assistant professor in medieval history, mentioned another divination practice similar to the Nutcrack Night tradition.

“There was a belief that if you eat an apple in front of mirror on Halloween, you’ll see your spouse over your shoulder in the reflection,” Archibald said. “A lot of the traditions have to do with seeing an apparition of your future spouse.”

Przybylek also explained that the origins of the jack-o’-lantern, that most people associate with Halloween and the harvest, actually comes from the practice of carving turnips that took place in ancient Celtic cultures in Ireland on All Hallows’ Eve to ward off evil spirits.

The name jack-o’-lantern comes from the story of Stingy Jack, who was an old drunk who played tricks with the devil and used a hollowed-out turnip with a flame inside it, or a lantern, in order to get out of hell.

“Like kale or cabbage, [turnip] was a subsistence crop,” Przybylek said. “The pumpkin, or the jack-o’-lantern, is a really great symbol of how the holiday morphed and enlarged when it came over to America.”

By the late 1850s, Przybylek said Halloween started to become an evening of tricks and jokes with people moving wagons on top of barns, turning signs over and knocking on strangers’ doors. In an area like Pittsburgh, that was then beginning to morph into a small city, Przybylek said it wasn’t a coincidence that pranking became more prevalent.

“I mean, what happens when you have a large cohort of teenage boys in an urban area?” Przybylek said. “I think some of the pranking grows out of growing population centers.”

Moving into the early 1900s, the holiday evolved into a more carnival-like event, according to Przybylek.

“There’s a lot of coverage of Halloween in Pittsburgh in the early 1900s where it’s almost like a street carnival,” she said. “Everyone comes Downtown, merchants board up their windows so they’re not broken [by people throwing things]. They used words like, ‘Oh, it’s like a Mardi Gras carnival.’”

By the time of Prohibition and the Great Depression in the 1920s and ’30s, when crime was becoming more widespread, the pranking associated with Halloween that was once seen as fun became more malevolent. Scholars debate that the practice of trick-or-treating was invented as a way to offset some of the mischief of children and young adults of the time, according to Przybylek.

“Some of the damages were someone putting an axe through a door, someone shot through a door … it just took on a very dangerous edge,” Przybylek said. “You begin to see towns on Halloween to do community events, a fun parade, [getting] the kids together at a party to dissuade them from going out and damaging things.”

Pranking was still a significant aspect of Halloween in Pittsburgh during World War II, but the police were more proactive about warning people about it in advance. After the baby boom from 1946 to 1964, the holiday was centered on families with young children.

But the malicious trickery associated with Halloween never truly ended. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette printed a story in 1986 about incidents of people tampering with Halloween candy, and in 1989 the Post-Gazette ran a story about X-ray screenings of treats that were conducted to ensure the candy was safe.

“St. Francis Hospital, which offered free X-ray service to anyone who brought in treats, reported that only one piece of tampered-with candy — a miniature Krackel bar with a small nail pushed through it — was detected at the hospital,” the article by Mike Hasch read. “Cheswick Patrolman Ike Zebrak said a small, red pill was found in a popcorn ball.”

Przybylek believes one of the reasons why Halloween has become the popularized, multi-million dollar event that is today comes from the same interest in what inspired those original Celtic divination practices.

“I think that the interest in evil spirits, superstitions, and the witches and goblins have been the part of Halloween that people have always enjoyed,” she said. “It’s really a remarkable cultural practice that has spanned throughout centuries.”

Even though Halloween has become this largely advertised holiday, Archibald thinks much of the original practices of celebrating the harvest are still prevalent today.

“I think in some ways the way that we celebrate Halloween as a kind of civic festival, not necessarily particularly religious … is not that far off from some of the things that influenced [Halloween] originally,” Archibald said. “It’s [about] celebrating the harvest festival and then associating that with the idea of the supernatural and an excuse for drinking and feasting and merry-making.”