Pitt faculty see future in union

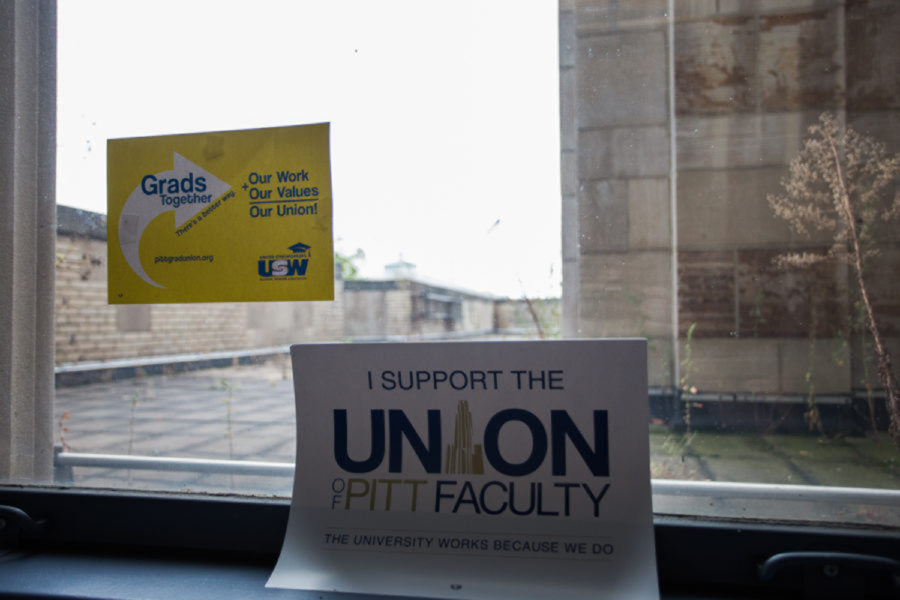

To most passersby, the fliers, posters and comics adorning the office doors in the narrow corridors on the fourth floor of the Cathedral of Learning blend in with the rest of campus. But for Tyler McAndrew, a visiting lecturer in the English department and prominent faculty union organizer, the posters that read “I support the Union of Pitt Faculty” represent years of grueling campaign work.

“I’ve been knocking on doors every week for the past two and a half years just trying to have conversations with professors about how a [faculty] union could improve their lives,” McAndrew said. “That effort began right here in the English department.”

McAndrew’s own office, nestled in a small enclave on the same floor, is outfitted with many of the same pro-union posters. But while McAndrew is heartened to see pro-union fliers scattered all across campus, he said the most tangible sign that organizers’ efforts were successful came last month, when Pitt filed for a faculty union election with the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board.

Pitt Faculty Organizing Committee began collecting signed, confidential union cards from more than 3,500 Pitt faculty last January. According to McAndrew, the organizers spent several years campaigning with their peers before even beginning to collect cards, attending monthly meetings, refining their talking points and ultimately going out into the field to persuade other professors to support the cause.

“We really needed to gauge interest among the faculty here at Pitt,” McAndrew said. “Once we started collecting cards, we only had a year to get at least 30 percent of professors on board for a vote.”

Once the PLRB verifies that more than 30 percent of faculty have signed cards, it will set a date for a union election, assuming the University doesn’t contest the filing. At least 50 percent of professors must vote yes to form a union of Pitt faculty, which would be affiliated with the Academic Workers Association, a division of United Steelworkers.

McAndrew said he’s unable to reveal the number of professors that signed cards, but he thinks the union bid will succeed if it goes to an election.

“We have supporters from all different departments, at all different levels with all sorts of different complaints about working life at Pitt,” McAndrew said.

Among the union’s staunchest supporters is Caroline Brickman, an adjunct professor in the English department who came to Pitt in 2018 after finishing her graduate degree at the University of California Berkeley. There, she was a member of one of the country’s largest university labor unions, which represents all the UC schools.

“I got my job when I still lived in California,” Brickman said. “I Googled, ‘Does the University of Pittsburgh have a faculty union?’ and I realized that there was the [card] campaign.”

Brickman believes every laborer should be represented by a union, and she has many job security- and pay-related grievances with the administration that pushed her into Pitt’s faculty union campaign.

“Adjuncts aren’t treated that well on an institutional level,” Brickman said. “I’m lucky enough just to get rehired every semester. I could be told a week before the start of the semester by the department chair, ‘Sorry, we don’t have any classes for you to teach next semester.’”

The dismal pay for adjuncts doesn’t help matters either, Brickman said. The Pitt faculty union website says pay per course can range from $2,500 to $4,000, which, full-time psychology professor Melinda Ciccocioppo said is far below the average pay for adjuncts at Pitt’s peer institutions.

“Pitt always says it wants pay to be at the median compared with its peer institutions, but every year, faculty members, especially adjuncts, are down toward the bottom,” Ciccocioppo said.

Pitt lecturers, who McAndrew said are “one step above an adjunct,” ranked 28th in annual salary when compared to 34 public institutions in the Association of American Universities, which is comprised of 62 distinguished public and private research universities across the United States.

Since Pitt’s holding onto its money with a vice grip, at least for part-time salaries, McAndrew said he had to work two- to- three jobs just to make ends meet as an adjunct — not the glamorous, high-end lifestyle he expected from teaching the next generation of scholars.

“I can say when I was an adjunct, I was teaching two classes [at Pitt] and working at a writing center twenty or thirty hours a week, and at points working a part-time service industry job, too,” McAndrew said.

And those long, taxing hours didn’t just take a toll on him, he said they also robbed his students of a great education at times.

“I’m a teacher, I love being at the front of the classroom,” McAndrew said. [But] I couldn’t pretend that I was coming in to teach with my mind not in other places.”

Even though Ciccocioppo works full-time and is “happy with her job,” she still worries about the University’s overreliance on low-paid contingent faculty, who teach more than a quarter of Pitt’s courses. She said the current system isn’t fair to adjuncts or students and thinks one of the first things a Pitt faculty union should do is institute a blanket pay raise.

“I think giving adjuncts a raise will be really easy once we have a union in place — it’s what we all want.”

Marian Jarlenski, a tenure-stream professor in the public health department, strongly agreed.

“As tenure-track faculty who have some sway with the administration, it’s our responsibility to stand up for those who don’t have the same power,” Jarlenski said. “Of course we stand in solidarity with adjuncts who aren’t being paid what they deserve.”

As McAndrew noted, some of Pitt’s peer institutions, like Rutgers and the University of Oregon — which are public and comparable to Pitt in size — granted one- to four-percent raises to all faculty immediately after forming a faculty union. And this is standard practice — when faculty unions draft an initial agreement with the university administration, they typically demand an “umbrella clause,” which gives a slight raise to faculty of every level.

That’s the easy part, McAndrew said. The challenging part is renegotiating employment contracts to give all faculty more job stability.

If the union bid succeeds, the first step would be to elect faculty representatives from each department who could set up a committee to peer review employees’ contracts and address other grievances within the department. While each department has a document outlining the path to promotion for tenure-track and full-time professors, Jarlenski said the criteria are vague and subject to personal bias — they don’t specify the number of hours professors must spend in the classroom or a research facility, for example.

“A lot of people don’t realize that the path to promotion for tenured and full-time professors is often just as cryptic as for part-time faculty,” Jarlenski said.

It’s unclear how many tenure-track professors eventually achieve tenure — universities don’t publish those statistics, and Jarlenski suspects the numbers vary between schools and departments.

For that reason, Ciccocioppo said, union organizers want to negotiate a legally binding contract to streamline the promotion process. Such a document would aim to eliminate bias in tenure selections and improve faculty stability across the board. Above all, Jarlenski said, it would set a precedent for better transparency between faculty and administration when it comes to major decisions — like tenure — that can make or break a professor’s career.

The administration also needs to be more transparent about how it allocates its funds, according to Brickman.

“Sometimes I just look at the students in my room,” Brickman said. “Let’s just say they’re all paying in-state tuition. A third of [one student’s] tuition is paying me. Where is the rest of the money going?”

Besides publishing statistics about student tuition, average faculty pay and total endowment, Pitt often doesn’t reveal where its money goes, she said. But since Pitt is a public university that receives state and federal funding, it’s required to publish a list of all expenses that exceed $1000 every fiscal year. The most recent financial disclosure report on the university’s website dates back to 2015, however. And the University did not provide a report from the past fiscal year — July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018 — in time for publication, despite repeated requests from The Pitt News.

This is the kind of “sloppy, or perhaps willful,” lack of transparency that the University can get away with when there’s no union to hold administrators accountable, McAndrew claimed. A faculty union could “force the administration to open the books,” since Pitt faculty would be able to sign a contract requesting more information about faculty salaries and other university expenses. McAndrew said this is one of many reasons why he thinks Pitt’s administration will contest the union.

“It means [the administration] has to go out of their way to make changes, and they have to be held responsible for things they haven’t been held responsible for in the past,” McAndrew said. “They don’t want anyone to disrupt the system.”

Pitt declined to say whether the University will contest faculty’s bid for a union. University spokesperson Joe Miksch said Pitt is still reviewing the petition filed with the PLRB.

“This is a faculty issue, and it merits careful consideration of the pros and cons involved,” Miksch said. “The University is dedicated to supporting the diverse interests of our faculty members … This commitment will not change, regardless of how this particular issue evolves.”

McAndrew said faculty interests are, in fact, somewhat diverse — he’s spoken with professors from various departments who oppose the faculty union. None of the professors The Pitt News spoke with opposed the union, however.

“The main [opposing] argument I’ve heard: some people see the union as a third party entity that’s going to make sweeping changes to university operations … Not so,” McAndrew said, rolling his eyes. “[United] Steelworkers is an ally, not a third-party.”

Pitt Faculty Organizing Committee’s campaign partner, United Steelworkers, is a union that provides legal and organizational assistance to smaller groups of laborers trying to unionize. The organization already has partnerships with faculty at other Pittsburgh universities, aiding the adjunct unionization effort at Robert Morris University and Point Park University in 2015. USW spokesperson Jess Kamm Broomell insisted that Steelworkers would have no decision-making power in Pitt’s faculty union, and it’s pretty “hands-off” with its other faculty partnerships, too.

“We’re here to be a resource for the union effort,” Broomell said. “We know the legal processes they have to go through, we know strategies that tend to work in organizing, but really it’s the faculty who are leading the way with this.”

The University has remained neutral toward the union in public, which McAndrew said he is grateful for. But he expects that to change as the PLRB gets closer to announcing an election date, especially given the way the University reacted to the grad student union campaign, which filed for election last semester.

Pitt hired the Philadelphia-based law firm Ballard Spahr, which offers “union avoidance training” and counseling to employers, to contest the graduate student union in 2015. The University then re-hired the firm to deal with faculty unionization less than a week after a faculty assembly Sept. 4, where union representatives discussed their struggles with job insecurity and low pay, according to reports from the University Times.

“That’s your tuition dollars at work,” McAndrew said. “It’s going toward union busting.”

Pitt declined to say how much money it has paid to the legal giant over the past three years, but researchers from USW think the total is significant — to the tune of a few hundred thousand dollars. Financial disclosure reports from the past three fiscal years, which aren’t available as of publication, would reveal exact expenses.

But Ballard Spahr doesn’t necessarily spell trouble for Pitt’s faculty, Broomell said. While Pitt, assisted by Spahr’s attorneys, argued that graduate students are not employees and therefore don’t have the right to unionize, the University can’t use the same argument against the faculty union, because faculty are, without a doubt, Pitt employees.

“The University can register any legal concerns they have about the union, but they can’t just unilaterally say ‘no,’ the way they tried to do with grads,” Broomell said.

Pitt faculty have attempted and failed to unionize twice before, most recently in 1996 when organizers failed to collect signed cards from a majority of faculty members. The first attempt in 1976 failed when faculty voted against the union 1,243-719.

But McAndrew is confident the third time’s the charm for Pitt’s faculty union.

“We feel pretty optimistic, I can say that,” McAndrew said. “We got more than that 30 percent of cards we needed to prompt an election.”

And that “more than 30 percent,” McAndrew said, will pave the way for 100 percent of Pitt faculty to negotiate pay, win better job security and ultimately give themselves a voice. He said the benefits of a faculty union can “lift all boats,” percolate into student life and enliven every organ of the University — not just those rows upon rows of faculty offices on the fourth floor of the Cathedral.

“We’re the ones on the ground working with students. It’s not the Chancellor, it’s not the administration, so they can give themselves raises all day long, but it won’t help students,” McAndrew said. “At the end of the day, the University should be serving its students. And in order to do that, they need to serve their faculty, too.”

Neena is a senior staff writer at The Pitt News who has covered Pitt's graduate student and faculty union campaigns since January 2019. Originally from...