How Swanson brings its tech to local businesses

Knox Coulter | Staff Photographer

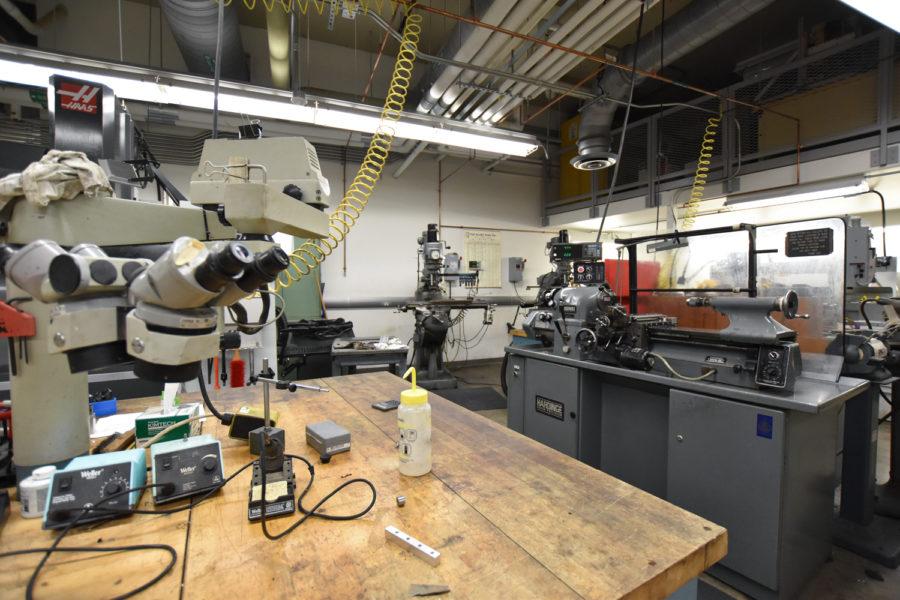

The Swanson Center for Product Innovation workshop. Knox Coulter | Staff Photographer

March 1, 2019

Skippy PI might sound like a film noir detective who’s sponsored by a brand of peanut butter.

But in the Swanson School of Engineering, it’s a shorthand way to refer to the Swanson Center for Product Innovation-Professional/Industrial. That’s a mouthful of a program where Pitt works with local businesses to design and prototype solutions to real world problems, with the help of students and Swanson’s advanced making technologies.

SCPI2 — the other way to shorten the name — is led by Jarad Prinkey, a 2000 Pitt graduate. Prinkey and SCPI2 helped design the product created by the winners of last year’s Performance Innovation Tournament — a small waterproof device to help swimmers analyze training techniques.

Prinkey came on a year and a half ago to supplement the skills of faculty working in the original SCPI, a more general resource center for students, faculty or outside partners that eventually became focused mostly on students’ work.

Now, Prinkey performs analysis for the projects before work even begins, to help businesses understand the workability, process and the eventual cost of producing prototypes and final products. In addition, he acts as an intermediary between the businesses that use SCPI2 and the engineering school’s resources, including the most plentiful resource at the University — the students.

Some students might work on a project for a small company to satisfy the engineering senior project requirement. For others, it’s about making a good impression with the company or building a resumé. There are even some courses through the center that allow students to take on highly technical projects that span many areas of expertise.

“Our primary mission here is to educate our engineering students,” Swanson Assistant Dean of Engineering Schohn Shannon said. “We always encourage, and we’re always looking for projects where we could involve students.”

According to Shannon, this can benefit the companies as well, since students are a cheaper alternative to professional development. Not every company is willing to give its project to undergraduates, but sometimes it makes good economic sense.

“Some people say no, we don’t want undergraduates working on this, which is fine,” Shannon said. “We’re talking to one [group] right now — they’re still not sure which way to go with it — and so they’re talking about ‘well, you know, maybe we could have two or three different student projects, where each of those teams of students is working on different projects, and determine which of those is the most viable.’”

SPCI was envisioned as a way to go from a concept to a workable product quickly and without needing outside expertise, according to Swanson Assistant Dean for Research David Vorp.

“[SCPI] was formed in 1997 in order to provide the school with a design and prototyping facility. It’s transformed over the years, and a few tweaks here and there, but it’s become very much a student resource,” Vorp said.

Over time, the students began to crowd out faculty and outside partners. The school needed a way to work on professional, educational and industrial projects separate from the students. Starting last year, SCPI was renamed SCPI-Academic, and SCPI-Professional/Industrial was created to handle those outside projects.

“The vision was to create this separate facility that emphasizes the use by faculty across the University, but also outside partners,” Vorp said.

Students can still work on those projects, as described above, though usually projects are initially taken on by a pair of experts — Prinkey, as SCPI2’s expert in electronics and software, and Andy Holmes, the current head of SCPI-A.

“[The University] brought me in, so we can actually make a whole device now. The parts, the case, whatever you need, Andy does, and then I do all the fiddly bits that go inside, all the sensors, and batteries, and microcontrollers and all that,” Prinkey said.

When SCPI2 came together, Prinkey was chosen to head up the department because he already occasionally helped with industry and student projects. Pitt holds Innovation Challenges, where students try to solve academic, athletic or educational problems they notice, and Prinkey learned how to work as an adviser by sitting down with students to help.

“With all the innovation activities going on at the University now through the Innovation Institute,” Vorp said, “[students] need to have a resource to help make them as a reality.”

Shannon says that the real value to the students comes from getting a hands-on approach to the material they’ve learned. While studying theory is important to a full education, there is a lot of value from actually working on a project without an instruction sheet or teacher to guide you.

“They’ve sat in the classroom for two or three years, learning the engineering background,” Shannon said. “This is their chance to get hands-on [experience].”