Editorial | States should follow Pennsylvania’s lead in pursuit of curbing gerrymandering

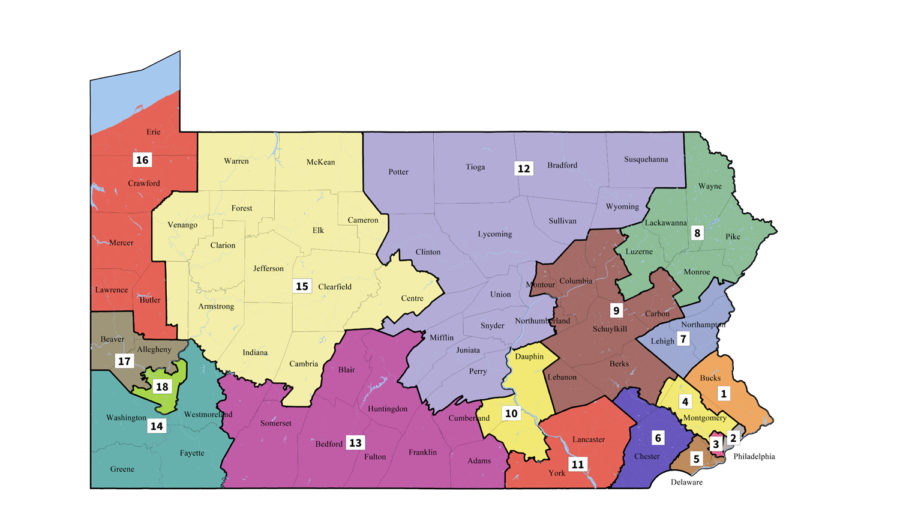

Map of Pennsylvania’s congressional districts.

July 9, 2019

Gerrymandering, or manipulating the boundaries of an electoral constituency in order to favor one party or class, may or may not violate the Constitution. What we do know is that the issue isn’t for federal courts to decide, as the Supreme Court ruled on June 27. Solutions or strategies to combat gerrymandering must come from Congress or be ruled within individual states.

“We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote.

Pennsylvania is ahead of the game when it comes to curbing gerrymandering. The state voted to redraw its heavily skewed Republican boundaries in February 2018, creating what many election experts considered a much fairer and more Constitutional map. Since individual states hold all the power to curb gerrymandering, they need to follow in Pennsylvania’s footsteps and prioritize making their maps as fair as possible.

States are required to redraw district lines every 10 years in conjunction with the updated United States Census. This helps address population changes in certain areas, by awarding additional House seats to rapidly growing areas, like Las Vegas. But the required redrawing is no help in curbing gerrymandering since the party holding the most power typically has the most say in the districting. In fact, both Democrats and Republicans spend millions of dollars on research and lawyers, hoping to find the most effective way to gerrymander in their favor.

Most states let their legislatures redraw the districts, though efforts to protect redistricting from gerrymandering have increased drastically over the last few years. Seven states, including Pennsylvania, redistrict via politician commissions, which are a designated group of elected officials who are in charge of drawing the new maps. There are typically a balanced number of officials from each party redrawing the maps, decreasing the likelihood of gerrymandering.

Other states have taken similar measures, like Alaska and Arizona, which require independent commissions. In an effort to keep the drawing fair, members of these commissions cannot be public officials or legislators.

Still, in most states, the legislature has the most control over redrawing lines. Regardless of the recent efforts to limit it, gerrymandering is far from gone. When states last redrew district lines around 2011, there were 340 districts that were not drawn by commissions and thus left in the hands of legislators. Republicans drew the district lines for 200 of these districts, and Democrats drew fewer than 50, according to The Washington Post.

Gerrymandering prioritizes a legislature’s political agenda at the expense of citizens, their individual voices and votes. Unless states take immediate action, state legislators will once again abuse their power when redrawing the lines in 2021.