Remembering Pitt English professor Chuck Kinder, 1942-2019

Emily Wolfe | Contributing Editor

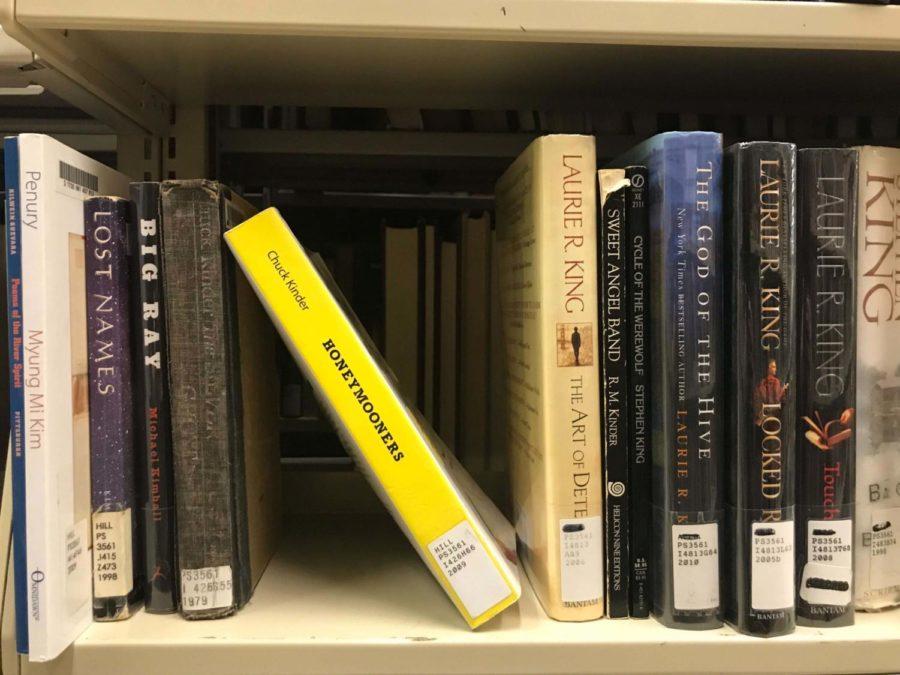

Kinder based his 2001 novel “Honeymooners” in part on his own life.

September 8, 2019

Instead of the standard suits and ties, most of the guests at Chuck Kinder’s memorial walked into the auditorium of the Frick Fine Arts Building wearing cargo shorts and flower-patterned Hawaiian shirts.

The unusual attire referenced the frequent gatherings that Kinder and his wife, Diane, would hold for students and colleagues in the English department at their Squirrel Hill home, where Kinder encouraged people to wear the patterned shirts.

The memorial was held Saturday evening to honor the life of Kinder, who passed away at the age of 76 in a hospital near his home in Key Largo, Florida on May 3. The event was attended by friends, former students and loved ones, who gathered to share stories and pay tribute to Kinder’s life and accomplishments.

Jane McCafferty, a 1989 graduate of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, was one of Kinder’s undergraduate students during the years he taught at Pitt from 1980 to 2014.

“He was a remarkably generous man,” McCafferty said. “He was a magnanimous figure.”

Similar sentimental phrases filled the auditorium as attendees celebrated Kinder’s life and influence.

Kinder was born in Montgomery, West Virginia, in 1942. Before becoming a professor in Pitt’s writing program, he earned a degree in writing from the University of West Virginia, and then went on to study at Stanford University through the Wallace Stegner Fellowship — earning one of five spots offered to fiction writers.

Outside of the classroom, he was a novelist and poet. He published his first novel, “Snakehunter,” in 1973, about a boy growing up in the Appalachian region in the 1940s. His most recent book, “Last Mountain Dancer,” was published in 2004, and is a work of creative nonfiction about Kinder’s return to his home state of West Virginia. Later in life, Kinder focused on poetry, publishing a collection titled “Hot Jewels” in 2018.

Pitt’s writing program and the Kinder family have established a memorial fund for Kinder, though they’re still working to decide how to use the funds they raise. The program also hosted Saturday’s event, led by Peter Trachtenberg, a writer and professor in Pitt’s English department.

Trachtenberg invited friends, as well as former students and colleagues, onstage to share their memories of Kinder. The speakers included Chuck’s brother David Kinder and writer Sherrie Flick, with music performed by Kinder’s longtime friend Bob Marion.

“[Chuck] had a tremendous appreciation for the awesomeness of the universe,” Marion said. “It was hard not to be inspired by him. He had such a fertile imagination and sense of humor.”

Rick Schweikert, another friend of Kinder’s, echoed this sentiment. The pair would have long, drawn out conversations about the universe while at his Key Largo home, Schweikert said.

“‘The way I see it,’ says Chuck, ‘It comes down to whether you see the universe like a mechanic or like a heroic poet,’” Schweikert said, quoting Kinder. “‘And we, my friend,’ says old Chuck, ‘are two such heroic poets. True poets like you and moi, we live our poetry out loud.’”

Marion, along with all of the other speakers, talked about his memories of the parties that Kinder would hold at his Squirrel Hill home — many of which took place by the small koi pond in Kinder’s backyard. At these parties, guests would gather around the pond and share a drink, a laugh or a story of their own.

On one occasion, after a koi fish passed, Marion said Kinder buried the fish in the backyard, and sang “Amazing Grace” to himself as he did. In memory of the story, Marion played “Amazing Grace,” followed by John Denver’s “Take Me Home Country Roads,” a favorite of Kinder’s.

Each speaker told fond stories of the times spent with Chuck in his home and out by the pond.

“Some part of me will always be leaning on a wall there,” Trachtenberg said. “Young, poor, nervous, but thrilled to be among other writers telling each other stories. Rooms erupting with laughter, feeling completely full.”

Roger LePage, a former student and friend of Kinder, helped Kinder construct the famous pond in his backyard. He reminded the audience of Kinder’s name for the Hawaiian shirts that they were wearing.

“The shirts we are wearing today are not Hawaiian shirts, they are ‘Pond Life’ shirts,” LePage said.

LePage said his favorite lesson Kinder taught him was that you don’t just build a pond — you build a metaphor for life. For many of the speakers, the pond and the memories they shared around it were a symbol of the kindness and warmth that Kinder endlessly gave them.

He was dedicated to helping people find their voice, according to Marion. He was in love with teaching, and his students were the most important legacy for him to leave behind.

Rege Behe, a reporter and long-time friend of Kinder, remembered the writer as “larger than life.”

“Trying to capture every essence of Chuck and who he was is like trying to describe an ocean or a mountain range,” Behe said. “Chuck’s persona was immense.”

One thing that Kinder’s brother David emphasized, which was echoed by many other speakers, was Kinder’s enduring sense of humor, especially closer to the end of his life.

“We’d talk, tell jokes and family stories,” David Kinder said. “One thing that he did more than anything is wake up, and see me sitting beside him, and he would ask, ‘David, is Trump still president?’”

Marion, who was close with Kinder up until the end, echoed the sentiment.

“As he got sick, the inner spirit just kept burning,” Marion said. “The joy of living and the joy of words … he loved that. That’s what kept him going.”

Flick, a writer and friend, spoke about how Kinder continued to write through every difficulty with his health, even as it became too much to bear. Flick read aloud a section of a poem that Kinder wrote, which is featured in his most recent book of poems “Hot Jewels.”

“A lonesome old dog barks in the moonlight off a mystery boat with blue running lights, anchored in Florida Bay,” Flick recited.

The poem, like many others in “Hot Jewels,” was inspired by Kinder’s days of retirement in Key Largo with his wife Diane, Flick said.

The final speaker of the night, Schweikert, a friend of Kinder, laid out every one of Kinder’s works of poetry on the podium before he spoke. He made great mention of Kinder’s legacy, noting that it lives on in his students even now.

One of the most important pieces of wisdom that Schweikert still carries with him came from a conversation that he had with Kinder one morning.

“Be the poet,” Schweikert said. “Live your poetry out loud.”