Tennis transfers settle into new homes after Pitt

Brad Puckett/USA Strategic Communications

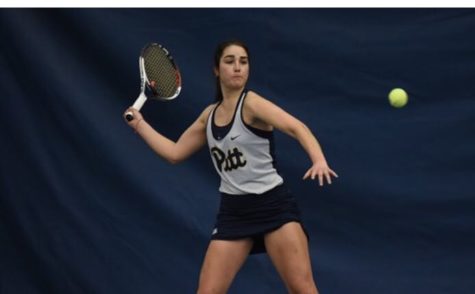

Junior Cami Moreno transferred from Pitt after the tennis program was discontinued and now plays at the University of South Alabama.

October 24, 2019

It’s now been more than nine months since Pitt Athletics Director Heather Lyke announced that the women’s varsity tennis program would be discontinued. The fallout from that decision was rough for everyone involved with the program. But perhaps no one felt the sting of its effect more than the Panthers’ three underclassmen.

Like the rest of the team, then-sophomores Claudia Bartolome and Cami Moreno and then-first-year Mariona Perez Noguera had to quickly deal with the shock of their program being cancelled. Though there had been rumblings that Pitt tennis could be in jeopardy, the players were still blindsided by the news.

“I mean, we heard some things, about the program and everything,” Bartolome said. “But we didn’t expect it at all. I thought maybe in a couple years, after I graduate. It was sudden. And also, our season was about to start, you know? We didn’t expect it at all.”

The timing of the announcement came on Jan. 10, with the team’s season starting shortly after on Jan. 18. Players were left with a brief one-week window to grieve and cope on the fly.

“I didn’t want to think about it,” Moreno said. “So I basically took one or two weeks off where I didn’t think about anything.”

Pitt’s four seniors were at least able to play out their final season, earn a degree from the University of Pittsburgh and move on with their respective lives. Bartolome, Moreno and Perez Noguera, meanwhile, faced a different set of challenges altogether.

“We had to … focus on the matches, even though we didn’t have reasons to win because the program was being cut,” Moreno said. “And at the same time, we had to talk with coaches about our transferring. So that was really hard.”

Pitt did its due diligence in offering to honor the three underclassmen’s scholarships. But all three ultimately came to school to play tennis. Being international students — Perez Noguera and Bartolome from Spain and Moreno from Argentina — they also came to the United States in general to pursue tennis.

“It was like — I don’t want to leave, but if I want to keep playing tennis I need to transfer,” Bartolome said.

Claudia Bartolome, pictured here in a February match against Georgia Tech, was one of three underclassmen who transferred from Pitt after the termination of the tennis program.

It’s not uncommon for Division I athletes to transfer schools. This is true for women’s tennis in particular — in 2018, the sport saw a student transfer rate of 13.0%, second only to beach volleyball. But nearly all of those athletes transfer under their own free will, typically due to frustration with playing time, rather than being unofficially forced out by a program facing extinction.

“It’s one thing if you want to transfer because you are not good,” Bartolome said. “But it’s another thing when you have to transfer.”

If there was any factor that made Pitt’s underclassmen hesitate to move forward with the transfer process, it was the relationships and connections they’d made on campus. Most sports teams are close, but having only seven players on the tennis team gave the group an especially tight bond.

“The first time I came to the United States, the idea was to stay at Pittsburgh for the rest of the four years there. So like, you meet people,” Moreno said. “For example, our team was really close, like we actually were a family. So, it was kind of tough to think that you weren’t going to be with them anymore.”

And so, each played through their final season at Pitt while actively reaching out to other coaches and trying to plan for a future elsewhere. The program’s impending demise wasn’t exactly a source of positive motivation, and the season went about as expected under the circumstances — a 4-18 record, down from 7-16 the previous year.

Each underclassmen did find a new home — Bartolome is in the midst of a productive fall season at SMU, while Moreno is also settling in well at South Alabama. Perez Noguera, who could not be reached for comment, now plays for the University of Louisiana.

Aside from the strenuous process of starting over at a new school, Bartolome expressed gratitude that SMU has more amenities for its tennis program. At Pitt, the team lacked an on-campus facility and had to commute 30 minutes to play in Wexford.

“Here [at SMU], for example, we have facilities that are on campus, and they’re amazing,” Bartolome said. “Many people go to the courts to play. And also, they care. They care more.”

The precarious situation of Pitt tennis’ remaining three underclassmen inevitably fell under the tough intersection of business and humanity. It’s true that the team had struggled, going 1-69 in the extremely competitive ACC after joining the conference in 2013. In her announcement, Lyke said it was unfair for the athletes to continue on in a program that lacked the proper resources.

“We have a responsibility to provide our student athletes with the finest opportunities to compete and achieve at the highest levels,” she said. “That, unfortunately, has not been the case with our women’s tennis program. Our analysis concluded this is a hard but necessary decision to ensure the best student athlete opportunities for growth and success in the future.”

That statement carried added shock value considering Lyke announced in November 2018 that she didn’t plan to eliminate any programs with the introduction of women’s lacrosse. Many players past and present felt that Lyke cut tennis without first putting in the effort to revive it. 2017 graduate Audrey Ann Blakely voiced this opinion in an interview last spring.

“They didn’t try a coaching change, they didn’t try building a facility, even a small minimum facility to have courts on campus,” she said. “Their first thing they did — as far as we can see, and we don’t know much more than the general public, unfortunately — is that they just went and cut the entire program.”

When asked if it would’ve handled the termination process differently if given the chance, Pitt Athletics declined to comment on the subject but added that “our former tennis student athletes have a standing invitation within the athletics department, and our various offices will always work to be the best possible resource for them in their current or future pursuits.”

Now, Bartolome, Moreno and Perez Noguera have found opportunities elsewhere with greater support behind them — though it came at the cost of their established residential, academic and social life.

“The hardest part was to leave the people you met there,” Moreno said. “Because tennis, I can play tennis everywhere. But people are kind of a different thing.”