Opinion | Mary Cain’s story exemplifies a larger problem in female running culture

November 11, 2019

It was primarily members of the running community who knew the name Mary Cain — until last week.

Runners knew her as the girl who became a professional athlete before even graduating high school, and at age 18, moved to Portland to train with the Nike Oregon Project and Alberto Salazar upon high school graduation. At age 17, Cain became the youngest athlete to ever make a 1500-meter running final at a world championship race in the spring of 2013. She was expected to be a podium contender in the 2016 Olympics, but after the spring of 2014, she stopped winning races. Eventually, she just disappeared, announcing in October 2016 that she was no longer training under Salazar. Cain was clearly struggling, but nobody really knew why.

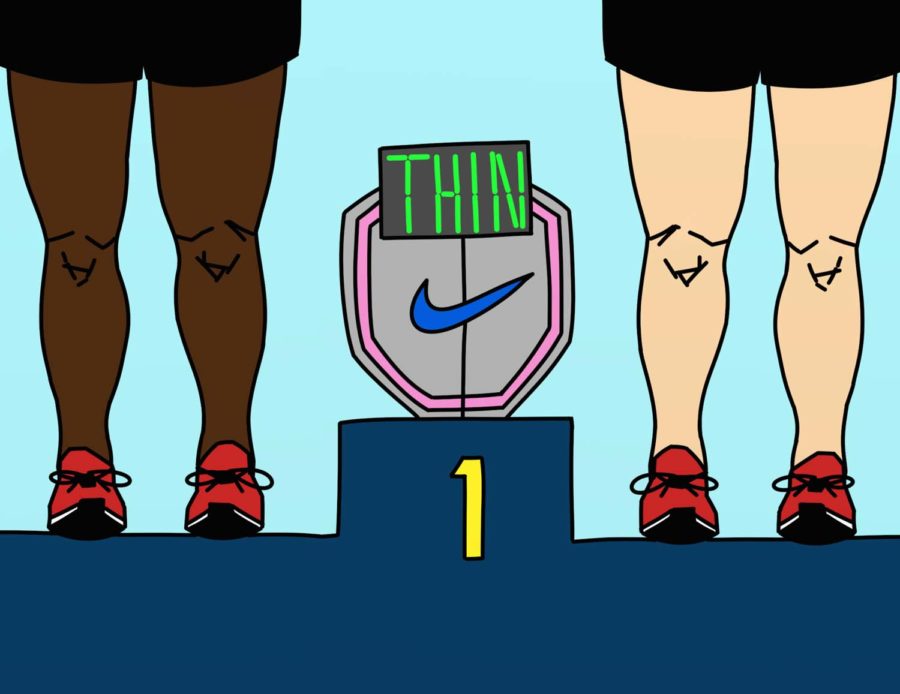

Now, we do. Cain was trending nationally on Twitter the morning of Nov. 7, after publishing a New York Times op-ed railing against both Nike and Salazar. According to Cain, Salazar and the male coaching staff wanted her to become, “thinner, and thinner and thinner.” Eventually, both her mind and body couldn’t handle it anymore. She began cutting and exemplified signs of suicidal ideation, though her coaches deliberately ignored her deteriorating mental health, she said.

Cain’s story has left people furious with Nike, especially considering its other scandals — doping, discrimination of pregnant athletes and advertising with Colin Kaepernick, to name a few.

But Cain’s story — one of the pressure to be thin in order to compete adequately, and the criticism of a coach and community that blindly encourages weight loss and thinness — exemplifies an epidemic in the female running community that systematically runs much deeper than just Nike. Of course we can, and should, be angry with Nike, but if we want to fix body politics in running, we need to look beyond a singular sponsor.

Since the release of the op-ed, countless professional female runners or those who have a link to the community have come forward, publicly supporting Cain and offering anecdotes of their own.

Adam Goucher, whose wife Kara Goucher is an Olympic silver medalist, tweeted about a coach telling him that his wife needed to lose her baby weight in order to become “fast again.” During the time of this conversation, Adam Goucher was standing at the finish line of the Boston Marathon — his wife had just placed fifth overall.

“Kara had GIVEN BIRTH 6 months prior and just ran 2:24,” Goucher wrote. “No celebration on her tremendous run, just judgement on her body.”

Cain acknowledges that weight does play a role in running, but then again, so does mental and physical health — which cannot be maintained at too low a body weight. There’s a common misconception in running culture that having a regular period means an athlete isn’t “training hard enough.” And this isn’t just a problem in professional athletics.

“It’s not just happening at the Oregon Project,” pro runner Allie Kieffer tweeted on Nov. 10. “It’s not just at Nike. I have seen this negative culture in colleges and even high schools. We need drastic change. Thanks to the brave souls who are joining the movement, because nothing changes if we sit in silence.”

In response and agreement with Kieffer, former NCAA runner Sarah Robinson tweeted Cain’s story with a concern of her own.

“Personally, I understood that losing your period meant you were in shape,” Robinson wrote. “I never lost my period, no matter how many miles I ran and constantly doubted if I was in shape because of it. WTF.”

Of course an athlete losing their period — medically known as athletic amenorrhea — isn’t normal. In fact, it’s extremely dangerous. If an athlete loses their period for prolonged amounts of time, the low estrogen levels often result in early onset of osteoporosis, infertility and low bone density. Cain says that she suffered five different stress fractures in the three years where she did not get a period.

This misinformation, and lack of conversation about it in the running community, is preventing the drastic change to which Kieffer is referring. With emphasis on thin bodies and lack of discussion about menstruation, the competitive running community often feels less like a catalyst for joy and endorphins, and more of a catalyst for disordered eating and body shaming.

In fact, over a third of NCAA Division I cross country athletes reported attitudes toward food and health that put them at risk for developing anorexia, according to the National Eating Disorder Association. This doesn’t account for college athletes who are not Division I, high schoolers or professional runners.

I was in ninth grade the first time I overheard one of my older cross country teammates say that getting a period meant she wasn’t training hard enough. At the time, I believed this to be true — nobody told me it was wrong. Now I realize that she was just repeating back what she heard everyone around her saying. Like too many others, it took me several years to understand how crooked this theory was.

The thousands of runners and non-runners alike who contributed to the conversation following Cain’s op-ed got the hashtag #FixGirlsSports trending on Twitter. Even more so than a problem with Nike’s ethics, Cain’s story exemplifies an epidemic in female running culture. One that certainly does need to be fixed.

The truth is, I don’t know how to fix girls sports — nobody does. Especially when it’s a multifaceted problem that runs as deep as amenorrhea, eating disorders and even a population of coaches that prioritize success over mental and physical health.

But Cain’s story is a start, and it’s spread discussion of taboos in the running community far past the running community for the first time. She was brave to come forward and share the horror she faced while running for Nike. Now, it’s up to us to continue keeping her story at the forefront. It’s our best hope for creating change in the female running community.

Leah is the opinions editor, and she writes primarily about essays and reading, mental health and the spices of the world. Write to Leah at [email protected].