Pitt, CMU engineers team up on low-cost ‘Roboventilator’

With an increasing demand for ventilators, researchers from Pitt and Carnegie Mellon University are collaborating to develop a lower cost “Roboventilator.”

May 12, 2020

As the United States passes 1 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, the demand for ventilators has dramatically increased.

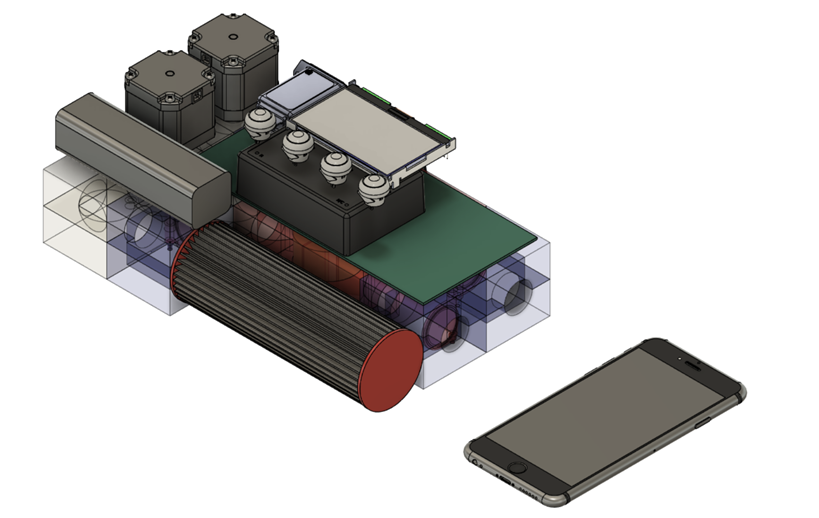

Pitt and the Carnegie Mellon University Robotics Institute have teamed up to address the shortage of ventilators created by the pandemic. They plan to produce a low-cost and nondisposable “Roboventilator,” an alternative to the traditional and more expensive mechanical ventilator. The Roboventilator will cost about $500, significantly lower than a traditional ventilator, which can cost between $30,000 and $50,000.

Planning for the project began in March, and is currently in the preproduction and crowdfunding stage. Jason Rose, a Pitt assistant professor of medicine and biomedical engineering, said he was interested in creating a ventilator with expanded and customizable ventilation capabilities.

“Many patients with respiratory failure require mechanical ventilation, including intubation and sedation,” Rose said. “The problem lies in that these normal ventilators used in patient care are too invasive.”

The Roboventilator does not require intubation — inserting an invasive tube into the windpipe — but instead augments normal respiratory function in a noninvasive way with either high oxygen levels or extra pressure to assist in breathing. Positive expiratory pressure is another feature of the ventilator that can control specific amounts of air pressure pumped into an afflicted patient’s lungs. Customizable ventilation modes are used for different patients to adjust for differing needs.

“The goal is to use sensors and actuators to do modern modes of ventilation,” Rose said. “The parts are easily fabricated and commercially available off the shelf.”

Keith Cook, a CMU biomedical engineering professor, collaborated with CMU engineers to develop low-cost ventilation. He worked with Howie Choset, a CMU computer science professor and project lead, who declined a request for comment.

“When I first went to Howie Choset about this, my first thought wasn’t to ask his group to work on a ventilator, per se, but to work on sensing and monitoring,” Cook said. “That would make these low-cost FDA-approved ventilators more efficient.”

Choset and his team integrated an automatic closed-loop system — where output is fed back into the system as input — and a modular design with easily interchangeable parts. Many of the ventilator’s parts, including the circuit board, will be produced with automation. But Lu Li, a CMU project scientist, said the team will need to rely on human production for short term needs.

“For a lot of components like the circuit board, we’re going to automate the manufacturing process,” Li said. “For final production, however, we do need help from other people.”

The Food and Drug Administration has already approved several low-cost ventilators for production from different companies, including a collaboration between Xerox and Vortran Medical. These disposable ventilators, which cost about $120 per unit, are not intended to replace traditional hospital ventilators.

“Even if the needs don’t become great in Pittsburgh, they may be great somewhere else,” Cook said. “If we can provide a lower-cost yet safe ventilator, potentially some of these lower-resourced areas around the world might be able to purchase some of these.”

Rose agreed that the next steps in developing this technology after final production would be sharing it with the world.

“There are many countries around the world that have a resource-poor health care system,” Rose said. “There could be hundreds of thousands of people around the world requiring mechanical ventilation at one time. They might have an easier time affording a Roboventilator than a traditional one.”

Kagya Amoako, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at the University of New Haven, was the first to publish research with Cook on artificial lung devices. Amoako is from Ghana, a developing nation with a population of about 31 million people that is currently facing a severe ventilator shortage.

“[Ghana] has 67 ventilators to care for its critically ill patients during this SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” Amoako said. “It’s therefore important, not only for the country but also for its neighbors and countries with a similar medical footprint, that we study and develop strategies that leverage existing and emerging ideas and turn them into accessible and effective respiratory care.”

Cook said it is critical that the government collaborate with academic researchers, clinicians and industry groups to help supply ventilators in the short run, and for the future of medicine in the long term.

“People can start working on prototypes, but they’re putting money out of their own pocket to work on these things,” Cook said. “At some point, somebody has to step up and provide the funds for further development.”