Law professor examines relationship between police training, brutality

David Harris led a presentation on the system of aggression created by “warrior policing.”

June 10, 2020

George Floyd. Breonna Taylor. Ahmaud Arbery. David Harris said these and more names of Black Americans who have been killed by police, while noting that the list is so long he would not be able to reach the end of it in his allotted time.

“The list is too long to finish and too horrible to contemplate,” Harris, a professor in Pitt’s School of Law, said.

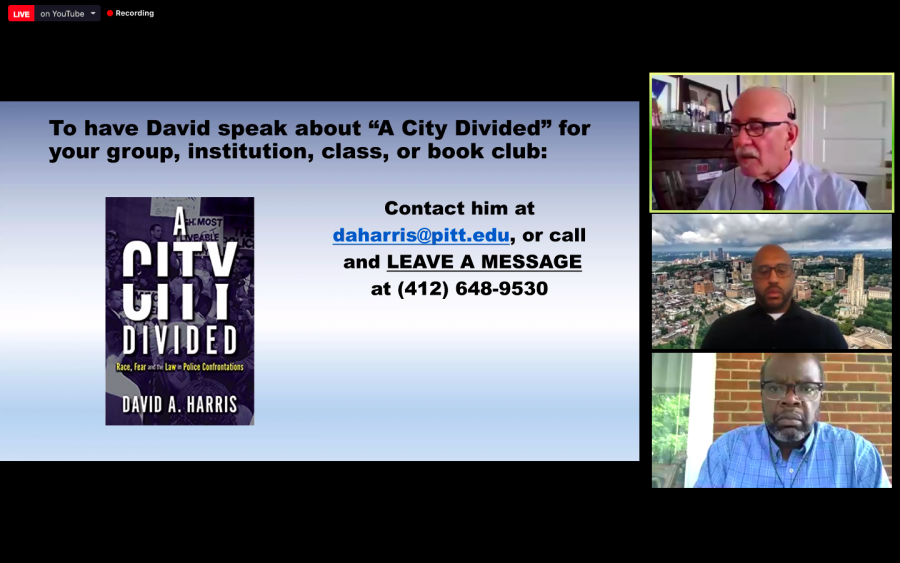

The University’s Center on Race and Social Problems presented “Race, Police, and Unarmed Civilian Deaths: What Can Be Done?” on Wednesday afternoon as part of its CRSPCast series. Harris, who also hosts the Criminal Injustice Podcast, led a presentation on the system of aggression created by “warrior policing,” followed with questions moderated by CRSP Interim Director James Huguley and John Wallace, a CRSP senior fellow.

Harris said warrior policing is a system of training that promotes the use of physical force by officers in the field. Police officers are taught that the use of force is a form of “righteous violence,” he said, that is always perceived as justified because they are fighting a “war on crime.”

“The presence of bravery and courage does not mean an absence of fear,” Harris said. “Fear is very much part of police training and culture today. The police are training in a certain way to try and overcome that, but it actually does the opposite.”

There is an entire industry dedicated to private training for police officers already in the field, Harris said, that structure their lessons around this “warrior” ideology.

“The idea of being a ‘warrior’ is simply this — there is a war going on out there, and police are the front line,” Harris said. “What our society finds so distressing in these interactions — disrespect, anger, violence — it is not a result of flawed training. It is a result of training for war.”

Harris cited recent data from The New York Times that Minneapolis police are seven times more likely to use force — through chemical irritants, neck restraints, canines, among others — on black citizens than white citizens. More often than not, Harris said, these incidents will involve more than one type of force.

“There is no reason to believe that Minneapolis is a lot better or a lot worse than most other cities,” Harris said.

When police are trained to treat their precincts as a battlefield, Harris said, fear pervades both sides of the interaction between police and the broader community.

“This results in incidents that should not be violent becoming violent, and those that are violent becoming lethal,” Harris said.

One way to reduce violence related to warrior policing, Harris said, is to change styles and instead follow a “guardian-based” policing model. This type of training treats police officers as protectors of “public peace and tranquility.”

“Guardian-based policing has a vision of police that will take care of their neighbors, and protect and serve them as neighbors,” Harris said. “That’s what we want our police to do, besides answering real emergencies. We don’t want them fighting a war.”

This kind of change, Harris said, is much closer to a reality in the United States than many citizens believe. California restricted its minimum legal justification for the use of force by a police officer in 2019 to only allow force when “necessary,” as opposed to when it would be “reasonable.” Rep. Summer Lee, D-34, introduced a similar bill last June which was referred to a committee for review, with no further action taken.

While this would only be a small change, Harris said the bill has the power to increase accountability of officers in the field. He said he has encouraged Pennsylvania legislators to think about if their experiences with police were different, and how this bill would impact the relationship between police and citizens.

“If your experience has included calling the police, and when they show up they’re pointing guns at you, you might feel differently about this,” Harris said. “Put yourself in other people’s shoes. Think about how people different than you experience police intervention.”

Once the community is able to empathize, Harris said, a change can be made.

“There are reasons people are upset, there are reasons to protest and there are reasons things must change. We cannot go on like this,” Harris said. “We have the power to be different.”