Legendary activist, track star John Carlos recalls ’68 Olympics

John Carlos spoke to about 30 Pitt students and faculty on Tuesday night about his life and experience at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.

July 8, 2020

For former track star John Carlos, “taking the podium” has a much different meaning today than it did 50 years ago.

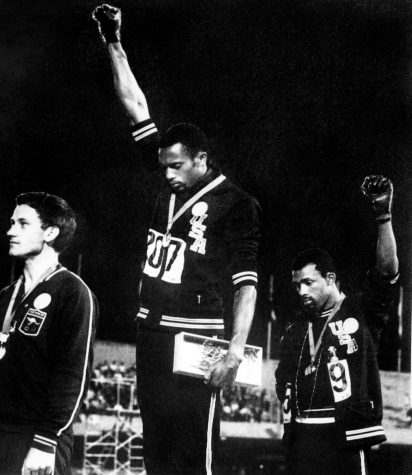

Hosted by Pitt’s Film and Media Studies department, Carlos spoke to about 30 Pitt students and faculty on Tuesday night about his life and experience at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. It was there that Carlos and fellow Team USA sprinter Tommie Smith posed for one of the most iconic photographs of the American Civil Rights Movement and sports history.

Life magazine photographer John Dominis captured the immortal protest after Smith took first and Carlos took third in the 200-meter race. Smith donned a scarf to represent Black pride and Carlos wore beads around his neck in a show of solidarity with lynching victims. Both were barefoot to call attention to Black people living in poverty.

“Our plight was not for Black rights,” Carlos said, “but human rights.”

The protest was far from spontaneous. It was carefully planned between Smith, Carlos and Peter Norman, the Australian who took second and — according to Carlos — his “brother from another mother,” from long before the games began to seconds before taking the podium. Carlos even said he has suspected the protest was decades in the making.

He recalled a then-frightening, but prophetic in hindsight, nighttime vision he had when he was a child.

“Sometimes I think I might be from out of this world,” Carlos said. “When I was 7 or 8 years old, whoever created this world gave me a vision of the stadium and the field. And I could envision the field and the crowd going crazy and cheering … usually when I do something I use my right hand, but in this vision I wave with my left hand … it shook me so bad.”

Later that important evening, Carlos’ father could see that he was upset and asked him why. After Carlos explained, his mother said, “God has something special planned for this child.”

Whether it was God or simply Carlos’ own talent, it took incredible circumstances for him to overcome the odds that were so clearly stacked against him. Carlos said he was proud of what he did to succeed, when failure was almost a guarantee.

“Probably the most pride I would have is — as a kid who came out of the slums of the city — to, so to speak, take chicken shit and turn it into chicken salad,” Carlos said.

Carlos grew up in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood in the ’50s, surrounded by drugs and unemployment. He said he was “blessed” to have grown up in a stable household, particularly when so many of his friends weren’t as lucky. Because job prospects were so few and far between, many fathers turned to drugs and a cycle of poverty was further perpetuated.

But Carlos, speaking of his father’s death, said he was lucky to have a supportive father who provided for him tangibly. With tears in his eyes, Carlos’ father expressed regret that he had nothing to pass to his son.

“I am about to leave this world, and I have nothing to leave you,” Carlos recalled his father saying.

Carlos responded and said, “I have the Carlos name … there is no me without you.”

Carlos said he had been provided with all he needed — a chance. And he ran with it.

After being challenged in school to learn geography — a task he deemed useless because there was no way a kid like him was going to travel to Europe — his teacher, Mrs. Seneca, told him that she was preparing him for greater things. From there he picked up track and prepared to expand his world beyond Harlem.

Carlos is still a champion today for change and believes that every athlete has not just the responsibility but the power to enact change.

“I think it’s all athletes’ responsibility,” Carlos said. “Anyone given a gift from God — entertainer, athlete — [has] to recognize that there are so many people from our neighborhood who didn’t make it, whether it be because of drugs or unemployment … it’s their responsibility and everyone’s responsibility.”

Carlos cites the forced sale of the NBA’s Los Angeles Clippers team, whose players threatened to boycott playing after racists comments made by owner Donald Sterling were revealed. He added that he wants to see former 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick leapfrog a playing job to become the NFL’s first Black owner.

Carlos said he believes the power of the athlete transcends age and race. As one of the few cultural phenomena to reach even the most radically different of demographics, the athlete has more power, particularly in the age of technology and rapid information, to push for social justice.

“That’s progression,” Carlos said.

Carlos said the goals of progression, liberation and freedom have shaped his life. In his most famous hour, standing atop his field as an Olympic medal-winner and proudly displaying a symbol of Black power for the world to see, that’s where Carlos said he felt the most free.

“I thought, ‘They could never put shackles on John Carlos’ mind or his body,’” Carlos said. “I was a free man.”