Let’s Get Free art contest raises awareness for women sentenced to life without parole

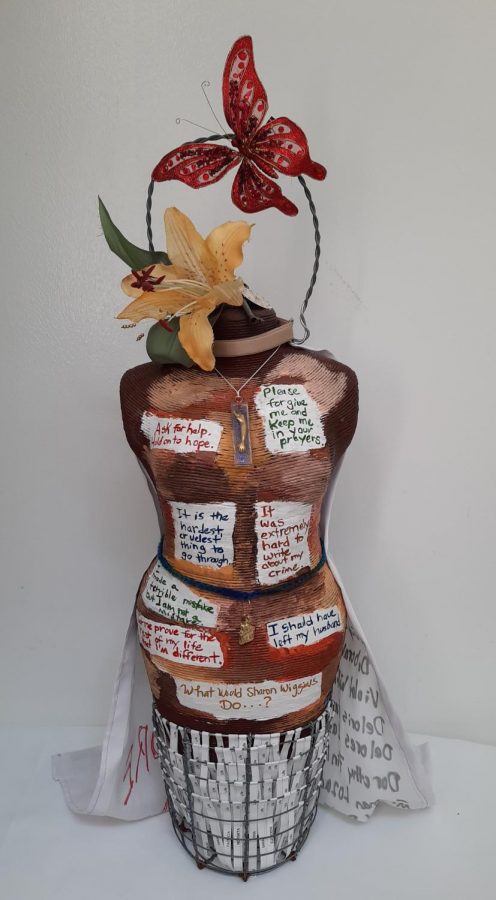

Photo courtesy of Ellen Melchiondo

“No More Names” by Ellen Melchiondo

August 26, 2020

There were 5,461 people sentenced to life without parole in Pennsylvania in 2017, according to a report by New York University’s Center on the Administration of Law. This sentence — known as death by incarceration — leaves prisoners with very limited opportunities to be released before dying in prison of old age.

The Let’s Get Free art contest hopes to raise awareness of the plight of these prisoners through several pieces by artists both inside and out of prison. The contest was organized as part of Life Cycles Toward Freedom, a multimedia campaign created by the Pittsburgh-based Let’s Get Free nonprofit group and the Women Lifer’s Resume Project.

Both organizations work to help women sentenced to life without parole. Let’s Get Free works to foster community ties between people in prison and people on the outside, assist people in applying for commutation and organize visits to prison, while the Women Lifer’s Resume Project works to document the growth of women lifers away from the people they’d been when they were first incarcerated.

Pieces for the contest went on display at Boom Concepts in Pittsburgh’s Garfield neighborhood on Aug. 7. Virtual tours of the gallery space have been held on Sundays, with the final tour taking place this Sunday on Zoom.

The Let’s Get Free website also provides a space to view the artwork, including a piece called “If we can break the system (Aging in Prison)” by Monica Davis, a Philadelphia artist. Davis said she took part in the contest because she knew people who were incarcerated.

“I decided to take part in this contest because I personally know of a couple of people who are incarcerated, that were wronged by the system. The idea of ‘death by incarceration’ can be extremely detrimental to a person,” Davis said. “I heard about the contest from one of the incarcerated individuals.”

Ellen Melchiondo, who submitted an art piece entitled “No More Names” for the contest, said her personal history assisting women sentenced to death by incarceration drives her work.

“Helping lifers goes back to about 2011 for me, when I met Sharon Wiggins at [State Correctional Institute] Muncy,” Melchiondo, a co-founder of the Women Lifer’s Resume Project, said. “She was a juvenile lifer and I knew her the last two years of her life before she died in prison in 2013.”

There are 62 pieces on display, including work by artists in prison and artists in solidarity. Pieces by artists in prison are being accepted until Sept. 30. Viewers can vote on their favorite piece from each category, and the winners in each category, who will be announced in October, will receive cash prizes.

etta cetera, a co-founder of Let’s Get Free, said the organization began doing art auctions three years ago.

“The past three years have been auction fundraisers, and that’s been actually the lead way that we raised money for our group, up until last year when we became a nonprofit,” cetera said.

In addition to the art contest, the Life Cycles Toward Freedom campaign also produced three short films, which were screened virtually via Zoom on Aug. 11, 18 and 23. The Let’s Get Free YouTube channel features clips from each of these films, which all center on women who have been sentenced to life without parole.

According to cetera, the art contest started a way to incorporate visual arts into the film campaign.

“We got a grant from Open Society Foundation to raise awareness about women and trans people sentenced to death by incarceration, so we’re making a series of films and we wanted to have a graphic component to that,” cetera said.

One film made by Life Cycles Toward Freedom is “Pennsylvania’s Commutation Process: Naomi Blount’s Experience,” produced by Tusko Films. The film screened Aug. 18, and the event also featured a conversation with Brandon Flood, the Pennsylvania pardon board secretary, and Naomi Blount, the second woman in Pennsylvania to receive a commutation in 30 years.

The two answered questions about the commutation process and challenges faced by former inmates who must adjust to life outside of prison.

Commutation allows people sentenced to life in prison to be released, as the short film explains. Applicants fill out the application, then have it reviewed by the Board of Pardons, which consists of Lt. Gov. John Fetterman, Attorney General Josh Shapiro, a psychiatrist, a victims rights advocate and a corrections expert.

According to the film, if a majority of the board approves the paper application, the applicant is then granted an in-person hearing where they must convince the dissenting members of the board to approve their application before it can be passed on to the governor, who can then choose to sign off on it. That last step can take anywhere between 30 days to three years.

According to NYU’s Center on the Administration of Law, commutations were much more common and the requirements were less strict before 1980 when Gov. Dick Thornburgh took office, only requiring a majority vote from the Board of Pardons to have an application sent to the governor.

Older prisoners tend to have their sentences commuted more frequently than younger prisoners, as Bert Grote, director of the Abolitionist Law Center and adjunct professor of law at Pitt, explained.

“The most consistently established empirical fact in criminology or the study of crime, perhaps, is that people tend to age out of crime, and this is kind of easy to think through,” Grote said. “Grandma and grandpa were wilder in their younger days, they’re probably a lot less wild now.”

But after a 1994 incident where commuted lifer Reginald McFadden went on a crime spree in New York, Grote said politicians and elected officials on the board have been hesitant to grant commutation, leading to only a handful of commutations in the last 30 years.

“If you don’t grant somebody commutation or even make a recommendation if you’re the lieutenant governor or attorney general on the board, you don’t have to worry about that person getting out of doing anything that reflects poorly on you,” Grote said.

According to cetera, Let’s Get Free helps people apply for commutations along with providing other services for people in prison or who have been released and need help adjusting to life on the outside, as cetera described.

“We do a lot of direct support for people in prison and outside of prison, or who have returned from prison,” cetera said. “If they’re incarcerated, we created a commutation support kit, which is information that helps people file their applications.”

Davis said taking part in the art contest has helped her learn more about these issues.

“I was actually somewhat aware of what women faced when being sentenced to death by incarceration,” Davis said. “However, this contest has opened my eyes and educated me on the full scope of what these women experience.”

According to the film, Fetterman and Flood have worked to reform Pennsylvania’s commutation process, but Grote said advocates such as Let’s Get Free and the Women Lifer’s Resume Project play a major role in ending death by incarceration.

“People serving life sentences, their advocates, their family members have been organizing big time to change public perception, to advocate in the courts in the parole board and elsewhere in order to push for second chances so that they don’t have to die in prison,” Grote said.