Pitt students work with Mattress Factory, honor artist Greer Lankton

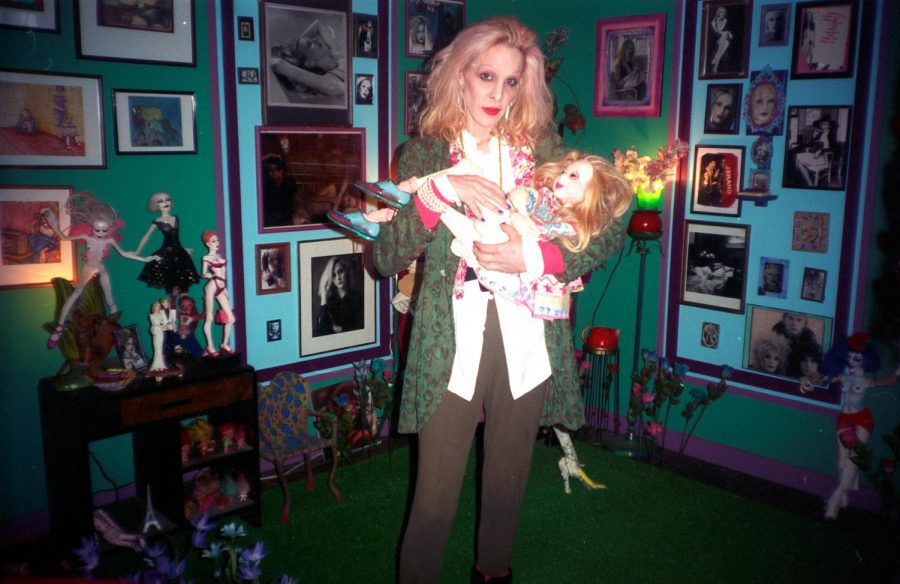

Photo courtesy of the Greer Lankton Archive | The Mattress Factory Museum Pittsburgh

“It’s all about ME, Not You,” is Greer Lankton’s permanent installation at the Mattress Factory museum in the North Side and was created in 1996.

November 4, 2020

An emaciated doll lays dramatically on bright red bedding, surrounded by a pile of empty prescription pill bottles and bunches of flowers. Naked mannequins and a crucifix hang above the doll’s bald head, and the room’s ceiling is dotted with stars.

This scene appears in the exhibit “It’s all about ME, Not You,” a permanent installation at the Mattress Factory museum in the North Side. Created in 1996 by artist Greer Lankton, the exhibit replicates the Chicago apartment in which she lived and created her artwork. Along with housing the permanent exhibition of Lankton’s, the Mattress Factory is currently working on digitizing an archive of more than 15,000 of Lankton’s works in collaboration with Pitt students. The project is due to finish by the end of 2021.

Lankton — a transgender woman and key figure in the East Village art scene of 1980s New York City — was best known for creating elaborate, lifelike sewn dolls and figures. According to Sarah Hallett, the archivist for the Mattress Factory, Lankton was involved in prominent New York galleries as a young artist.

“Greer lived in New York City for a while, where her work was shown by lots of galleries in the East Village,” Hallett said. “One thing that’s really significant was her involvement with Civilian Warfare, a gallery that was really important in the growth of punk and activist art.”

Lankton tragically passed away in 1996 from an overdose shortly after debuting her exhibit at the Mattress Factory. But the museum is still honoring her memory to this day.

Lankton grew up in the Chicago area, but moved to New York City to pursue art at the Pratt Institute. She exhibited her iconic doll sculptures, which exemplified recurring themes of gender and sexuality, at prominent art shows such as the Whitney Biennial and the Museum of Modern Art’s PS1.

Over the years, Lankton’s family has donated thousands of her artworks and personal belongings to the museum. In collaboration with Pitt students, the Mattress Factory is working on digitizing this archive of thousands of Lankton’s personal items and artworks.

Lankton’s family donated much of this work to the museum in 2014. According to Hallett, the museum put up these works for display in 2017 and 2019 but are just now becoming a digital archive.

“We received her personal work, some photographs, papers, 2D artwork, ephemera, newspaper clippings, journals, all kinds of stuff,” Hallett said. “In 2017, we went through all of it, and we selected works to go on display, and then we did basically the same thing again in 2019.”

Molly Powell, a senior studying history of art and architecture, is helping to digitally archive some of these works. As both an intern and subsequently a research fellow, Powell got the opportunity to personally organize and digitize Lankton’s artwork.

“The project that I’m working on is going through and digitizing the contents of the archive,” Powell said. “I’m dealing with different works, photographs, letters, etc. and then scanning and taking photos of the art so it can be preserved digitally.”

Specifically, Powell said she had to organize the artworks in a way viewers can access them online.

“I went through and organized a bunch of her 2D artworks by size and medium,” Powell said. “I got those shaped up, and then I took a bunch of her personal photos, scanned those and put metadata and information on a big Excel spreadsheet.”

According to Powell, even if that type of work seems boring, it is still rewarding being able to personally connect with the artwork.

“That kind of stuff is really important for archival work,” Powell said. “You need to know all of the boring stuff like the pixels and bit rate. That was really it, but it was a long process because they have thousands of photos that are all really charming.”

Lankton constantly photographed her life. Sinéad Bligh, the digitization archivist for the project, said this archive provides an in-depth catalogue of Lankton’s life through her artwork.

“It’s really clear that we can learn so much from the documentation of Greer’s work,” Bligh said. “She photographed everything all the time, so it was kind of a cataloguing of life in an artistic kind of way.”

Bligh said for her, the archive also serves as a preview into life in the East Village from the early ’80s to early ’90s and the impacts of the AIDS crisis. Additionally, it assists viewers in understanding the struggles Lankton faced as a transgender artist.

“The point of the digitization project is to allow access to all of those objects online and to invite larger historicization of her life as an artist and her struggles as a gay, transgender person, the histories of the New York Art scene and of the AIDS crisis and the ’80s and ’90s,” Bligh said.

According to Powell, the opportunity to work with this archive was a great way to understand what working behind the scenes in a museum entails. Along with it being a learning experience, Powell said she also had a lot of fun.

“It was a really great experience, and it was definitely fun,” Powell said. “I had been interested in working behind the scenes in the museum field, so getting the chance to work in an archival position was really interesting.”

According to Bligh, the collaboration with Pitt students has been very helpful. Previously, a researcher flew in from California to assist them, but now that Pitt students — such as Powell and Isaiah Bertagnolli, a graduate student in history of art and architecture — are working on the project, the collaboration is happening close to home.

“The collaboration with Pitt has been really fruitful, and working with Molly and the other interns was incredible,” Bligh said. “In order to give a broad history of an artist, it’s important to get lots of different views on it.”

When finished, the archive will be available online on the Mattress Factory’s website. With this project, Bligh hopes the archive will provide an accessible, holistic view of Lankton’s life via her artwork.

“At one point, nothing was really organized, so the hope is that people will now be able to use it easily online,” Bligh said. “I think it will be a much more holistic kind of view, which is much easier to navigate than digging through boxes.”