Opinion | America’s schools need to improve second language programs

November 15, 2020

We all know that language learning is hard. Some people love it, others hate it. Others think they can’t do it, have tried for years or wish they were raised bilingual.

The socioemotional benefits of learning a language are well known. Being fluent in another language makes you a more competitive candidate in the job market, gives you a more worldly perspective, makes travelling to a foreign country a lot easier and allows you to talk to and make connections with more people.

What isn’t as well known are the cognitive benefits of knowing another language. Being bilingual has been shown to aid in developing strong critical thinking skills, learning other languages, thinking about other languages, understanding difficult concepts, focusing, remembering and making decisions. Bilingual individuals are able to switch back and forth between more than one language with ease. This leads to a higher level of abstract thought and the development of more flexible approaches to problem solving. In other words, bilingual or multilingual people are better able to “think outside of the box.”

Speaking more than one language is amazingly useful and has been shown to have a multitude of benefits that range from socioemotional perks to benefits in learning and cognitive function. A very large percentage of people around the world speak more than one language, so why doesn’t America reflect that? The problem rests within our second language education systems. In a country with one national language, it is essential to have strong second language education systems in place to ensure language learning. Currently our second language education systems pale in comparison to those around the globe and are not nearly equipped enough to ensure bilingualism or multilingualism in students.

Many countries have more than one national language or many different dialects of languages spoken among their people. Throughout the world, 60% to 75% of people speak at least two languages and benefit from all the perks of being bilingual or multilingual. In America, however, only about 20% of people can converse in another language.

Language is something we learn immediately, and research has shown that we even start to learn language while we’re still in the womb. Studies have shown that babies can even distinguish language sounds that aren’t from what will be their native language, something that most adults can’t do. This, along with the other critical periods for language development, are the reason that children with parents who speak other languages often catch on pretty quickly. After about 5 years old, children begin to pass that critical period for language development, making it much harder for a child to learn a second or third language. Luckily for Americans, preschool starts at 3 years old. Language learning has to start early, and preschool is the perfect place to start that education.

But second language education doesn’t stop there, and it shouldn’t. Changes are needed from kindergarten levels through college and university education. We never stop learning language, and in grade school we learn more specific vocabulary and grammar rules and how to practically use the language in a way that makes sense. Many children, however, don’t start second language learning until middle school or even high school, and by that point, it is much too late. Studies show that second language learning must begin by age 10 for a person to be able to speak with native fluency.

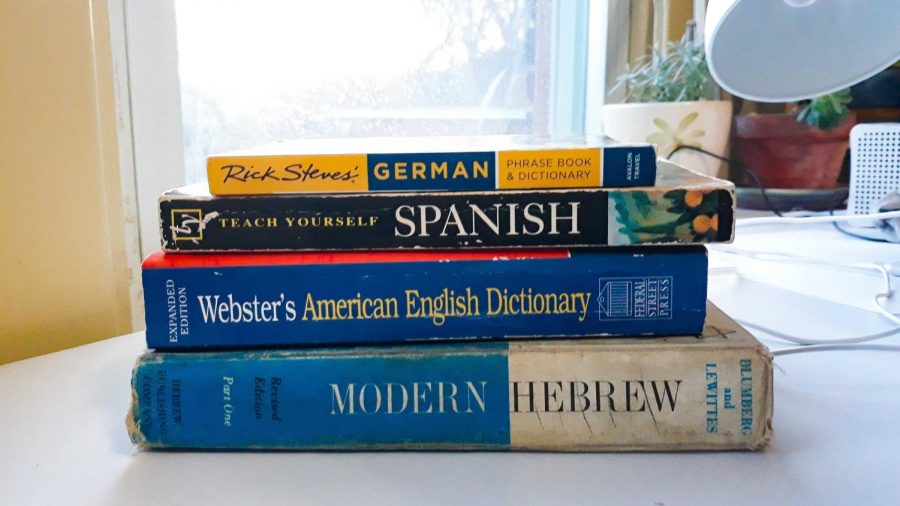

Not just the time in which we start teaching a second language needs to change, but also the way we teach it. Anyone who has taken a language class knows that doing bookwork all day will not improve how well you speak a language, and it will not make you enjoy learning the language either, which is essential for language learning. My brother has been taking Spanish classes for approximately nine years and still can barely speak a word, and he is not alone. Our curriculums need to change to reflect language learning in the real world.

The best way to learn a language is complete immersion, but many cannot afford to travel to another country for several months to immerse themselves in a foreign language. Not all hope is lost, however. Polyglots are people who have a high degree of proficiency with several languages, and many did not start out being so called “language people,” or people who thought they had a knack for learning languages. Despite having critical periods for language learning, language capacity extends throughout life. So if you’re 30 and trying to learn French, it will be hard, but there’s still hope for you. Our brains are hardwired to learn language, and keep at it long enough, you will learn. We just have to learn in the right ways.

In her quest to find out how other polyglots like her learned so many languages so quickly, Lýdia Machová found that everyone learns languages in their own way, but all had one thing in common. They had all found a way to enjoy the language learning process, create effective methods for learning and scheduled language learning into their everyday life. If the most effective language learners are using these methods for themselves, and are gaining fluency in a language every two years, then why don’t we apply these same methods to school curriculums?

By making language learning curriculums flexible and allowing students to learn in a way they enjoy while still keeping the structure of learning every day, and giving them guidance to find the way they will learn best, we can work to solve the problem of monolingualism in the United States. Students will be motivated to learn language because it will be fun for them, and they will no longer dread speaking in Spanish class or doing boring bookwork. The hands-on experience with language mimics the same hands-on experience we have when we first learn how to talk, write and read.

Second language learning needs to take a greater priority in our school systems. In the United States, we are behind in how we learn languages. For progress to occur, schools need to reform the systems and curriculums in a way that allows for students to start learning early and that will motivate students to stick with language learning for the many years of resumés, job interviews, travels across the globe and learning to come.

Dalia Maeroff writes primarily about issues of psychology, education, culture and environmentalism. Write to her at [email protected].