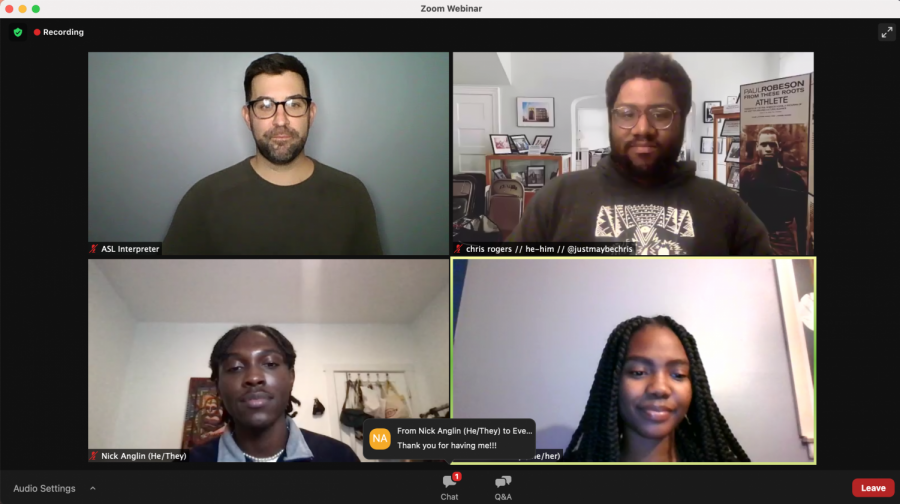

Black community leaders discuss youth organizing, Black Lives Matter in education

Pitt’s School of Education hosted a virtual forum Wednesday evening featuring community leaders and a discussion about current organizing work and future justice goals. At the end, Nicholas Anglin, one of the founders of Black, Young & Educated, spoke about encouraging sustainable action and community education to address racial inequalities and issues within cities like Pittsburgh.

February 5, 2021

This year’s Black History Month is particularly momentous, as it comes after a year filled with mass protests around the country for racial equity and police reform. As one of the first events of the month, Pitt’s School of Education hosted a virtual forum Wednesday evening featuring Black community leaders and a discussion about current organizing work and future goals.

At the event, Nicholas Anglin, one of the founders of Black, Young & Educated, spoke about encouraging sustainable action and community education to address racial inequalities and issues within cities like Pittsburgh.

“I remember I went to one protest in May, and I was like ‘we have to be consistent,’ because I always do organizing and I’ve always been going to protests, but I always felt like protests would die down within a few weeks,” Anglin, a first-year student at Temple University, said.

Part of the problem, Anglin said, is that Black people are not being heard when they speak up about issues directly affecting them.

“My experience is that most times we do feel unheard, we feel like we’re not heard in the classroom, we’re either not heard in multiple senses, in work places, at home, you know,” Anglin said.

Anglin spoke about his past experiences in high school, where he said faculty dismissed ideas he and other students came up with, even though many of them were “pretty simple.”

“Going on to post-secondary education, in college, a lot of the schools are predominantly white institutions,” Anglin said. “We have to have a setting that isn’t moderated by the schools, that allows Black people to use their voice and to voice their concerns.”

Chris Rogers, the national curriculum chair for Black Lives Matter at School, also spoke about the need for honest conversations and community connections in order to make real changes in the fight for racial equity. Black Lives Matter at School is a national coalition fighting for educational justice within schools.

The coalition curates curriculum and lesson plans for educators to help build upon the Black Lives Matter network’s guiding principles. Lesson plans also address Black Lives Matter at School’s four core demands, which are centered around protecting Black students and encouraging Black history classes for all students.

“We provide templates for educators to think about ‘how are we teaching racial justice within our classrooms?’ and we match that with thinking of educational policy and service,” Rogers said.

According to its website, the Black Lives Matter at School movement began in 2016 when thousands of Seattle educators wore t-shirts to school with the phrase “Black Lives Matter: We Stand Together.” The movement has since grown into a coalition stretching across the country, and the members work to organize for racial justice within the education system.

Part of Black Lives Matter at School’s work goes toward planning for their “Week of Action,” which takes place during the first week of February. Roger said the week is a way to “lift up” the organizing done throughout the year.

“Whether those are personal victories, personal reflections or personal acts of resistance, and then the ways that we kind of continue to build collectives and study groups and engage in collective action and collective resistance in a variety of ways,” Rogers said.

He said the coalition sees itself as a “bridge space” between ongoing Black-led organizing and the educating that is taking place in schools. Members of the coalition’s steering committee learn from the resources and actions utilized by organizers around the country and connect everything to the lesson plans they create for educators.

One organization that Rogers mentioned was the Alliance for Educational Justice, a national alliance of youth organizations and intergenerational groups. He said Black Lives Matter at School has utilized strategies and resources similar to those used by members of the alliance, and these strategies have helped them prepare teachers to help remove police from their schools.

Anglin, on the other hand, works with BYE to educate community members outside of the school setting. Throughout the summer of 2020, he and other members would have Civil Saturday protests in varying locations around Pittsburgh, speaking on issues that directly affected people in whichever area they were in.

“Every Saturday we would talk about different topics like transphobia, gentrification, based on the location of where we were protesting,” Anglin said. “So, when we protested in Lawrenceville, we focused on gentrification.”

A similarity between the work of both Anglin and Rogers is an emphasis on school policies.

“I think what’s missing, for the most part, is folks think that the school itself is the locus of change and not thinking of their relationship to young people, their relationship to families, their relationship to the community institutions that are around them that are already doing this work and have old solutions to many of the problems that they are seeking to address,” Rogers said.

C’enna Crosby, the event’s moderator, spoke about the importance of community and called for collaboration as well.

“One thing I think is, people don’t realize how important that connection between community and education in schools is, it has such a big impact,” Crosby, a senior applied developmental psychology major, said. “The schools can’t do it alone, they need that support, we need more collaboration.”

This collaboration is particularly vital when it comes to younger generations, according to Anglin, as organizing is the best way to accomplish a goal.

“It starts with one person, one person starts a conversation,” Anglin said. “Adults can be stuck in their ways, but honestly, we’re the new generation, we need to be part in building the world that we want to see.”