Pitt minor leaguers traverse obstacles on and off the field in pursuit of MLB dreams

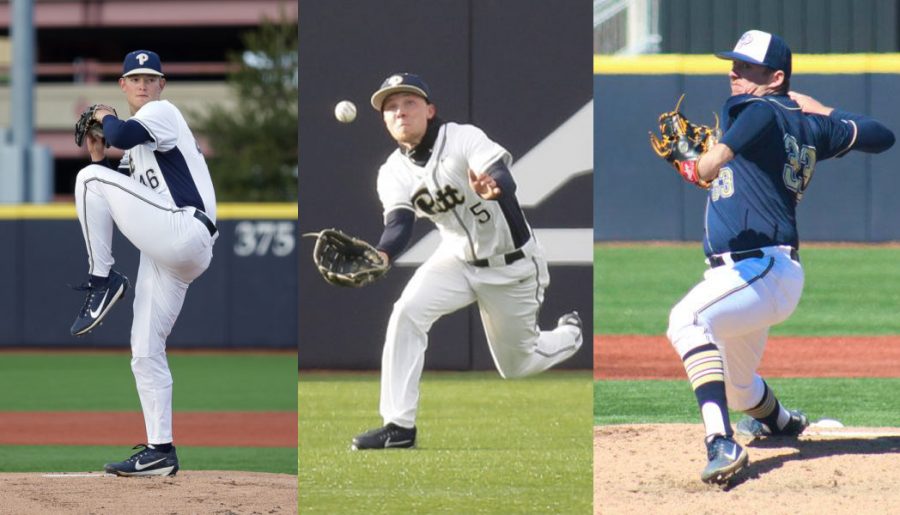

Left: Derek West in 2019. Thomas Yang | Senior Staff Photographer. Center: Connor Perry in 2018. Thomas Yang | Senior Staff Photographer. Right: RJ Freure in 2018. TPN file photo.

February 17, 2021

A professional sports career seems like a utopian fantasy to most of us average Joes, whose peak moment on the playing surface most likely comes when they catch fire from deep in their weekly church basketball league. It takes a tremendous combination of skill and hard work to make one’s way into collegiate sports, and fewer than 2% of college athletes will play professional sports at any level for any amount of time.

Once an athlete breaks into that prestigious echelon, the hardest work and stress has to have passed right? They’ve beaten all the odds, now it’s time for the infinite money, fame and glory. Right? If it were only that simple.

While sports fans gawk at Los Angeles Angels superstar Mike Trout’s 12-year, $430 million contract extension, the majority of players in the sport must delicately budget their earnings to survive. While the minimum major league salary is $563,500, a lawsuit filed by a group of minor leaguers in 2014 claimed most earn less than $7,500 annually. Though the MLB did raise the minor league minimum salary slightly for the 2021 season, the new wages for their three-month or five-month season still do not guarantee minor league players a livable wage, as they do not receive compensation during the offseason or spring training.

Former Pitt outfielder Connor Perry, who the Detroit Tigers selected in the 28th round of the 2019 MLB Draft, knew the financial reality he’d face going into the league.

“I signed for a bag of chips to play professional baseball,” Perry said with a laugh. “We do get paid in-season. Is it a lot? No. But, I think a lot of things in life are perspective, so I kind of don’t worry about that financial aspect right now, I just kind of enjoy playing the game.”

Perry, like most of his ex-Pitt teammates in the MLB farm system, must find work in the offseason to support himself. He gives baseball lessons, coaches and runs camps near his hometown of North Huntingdon, Pennsylvania. He even founded a summer baseball league this summer called the AAB Collegiate League, which attracted over 114 players, including senior Pitt outfielder Nico Popa.

Perry hosted a Team All American hitting camp in the Pittsburgh area this summer.

“I started my own collegiate baseball league kind of as a joke, and it just took off,” Perry said. “That was one kinda cool thing I did in the offseason to put some money in my pocket as well as help these guys out.”

A message on behalf of the commissioner, @c_perry33 pic.twitter.com/Z2Ipn9S4hu

— AAB Collegiate League (@AabLeague) July 31, 2020

Perry’s story represents just one of many Pitt alumni minor leaguers finding ways to make money in the offseason, while making important impacts on many people in the process. Former Panther pitcher Derek West, drafted by the Houston Astros organization in 2019, found more than just a cash-grab in his offseason job in Delray Beach, Florida.

West worked with the Drug Abuse Foundation from September to January, monitoring, supervising and teaching recovering drug addicts and alcoholics on their road to sobriety. He said he wanted to make an impact this offseason, and the shocking drug-related deaths of MLB pitchers Jose Fernandez and Tyler Skaggs helped open his eyes to the issue.

“Not a lot of people like to talk about that kind of issue,” West said. “These people aren’t defined by their addiction. It’s not their character, it’s not their personality. It really gave me a new perspective in this world.”

Although he recently had to leave his position to report to the Astros’ rehab camp, as he recovers from tearing his ACL at the start of 2020, West said he definitely wants to return to this area of work in the future, adding that the DAF wanted to hire him as a facilities manager if he didn’t go back to baseball.

“I really made an impact there, and I came up with creative ways to emphasize rehab and getting your life together,” West said. “We would teach the clients and come up with different situations and scenarios to help them understand and gain the knowledge from another person’s perspective.”

West said hearing the experiences of what his clients had gone through and the mental strength they endured in their path to recovery has changed his life. He had a glove custom made for this season in his work colors, with the letters “DAF” lining the side, to represent the people he helped at the organization on the baseball field.

West worked at the Drug Abuse Foundation in the offseason, and will wear the letters “DAF” on his glove this year.

West said he worked part-time at Pizza Hut on Baum Boulevard when he attended Pitt, so he has long become used to balancing a hectic schedule on and off the field. Alternatively, fellow Panther alum and Astros minor leaguer RJ Freure only has one source of income now — his baseball salary. As part of his temporary work visa, the Canadian pitcher said he can’t legally accept another job during the offseason.

Minor league players often receive host families — volunteer households that provide players with food, shelter and more — easing some of the stress off the field during the season. Freure said he had a particularly great experience with his host family in Davenport, Iowa, who attended all of the games he pitched in support. He even gave the couple’s son, who pitched for his high school team, some professional pointers from time to time.

“If I needed to throw one day and we were off and none of my buddies were going in, I’d say ‘Hey, you wanna go throw on the fields?’” Freure said. “He’d always say yes, so I’d take him down and allow him to be on the field of the stadium he’s usually in the stands for. We just got to play catch and have some fun out there.”

Using initial investments from his salary and draft signing bonus, Freure has carefully budgeted his offseasons to make sure he gets everything he needs, while focusing almost entirely on practice. After the MLB cancelled all 2020 minor league seasons in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, restricting access to team training facilities as well, he remained in Pittsburgh to train with other former Panthers in the area.

Although he and his peers ad-libbed plenty of their workouts — setting up a net in a backyard with a homemade mound — Freure kept in constant communication with the Astros organization to make sure he used his sessions effectively. He said they focused on hip mobility, strength, agility, body mechanics and pitch development.

“I took every piece that I was probably lacking or short of and tried to use that time to get up to where they expect me to be,” Freure said. “A lot of it was you throwing on your own or with other people to achieve this, but it was their ideas that you had to find a way to kind of run with.”

For West and Perry, the cancelled season actually came at a somewhat convenient time. Both were rehabbing from injuries sustained in 2019 — West’s ACL and Perry’s wrist — so the two didn’t wind up missing as many game opportunities as they would have without the pandemic.

The timing of the injuries did present a brief scare, though, as minor league teams released players en masse amid the pandemic last summer. West said he felt his ACL tear would put him first on the chopping block. But now that they’ve made it out alive, the two can’t wait for the 2021 season to arrive.

Expect most teams to make minor-league cuts in coming days. Said one agent: “40 players per team just got whacked so the club could save $50k/month. This is the equivalent of trying to save money by cutting out your daily Starbucks trip but still driving an X5 you can’t afford.”

— Robert Murray (@ByRobertMurray) May 28, 2020

As these young prospects chase their MLB dreams, former Panther outfielder Jason Conti recalls that craving for success before reaching the biggest stage. But as a 32nd round pick in the 1996 MLB June Amateur Draft, Pitt’s all-time stolen base leader never could’ve imagined he’d play at the highest level.

“Back then, anyone that got drafted in the 20th round or higher, if you’re thinking about the major leagues, you’re nuts,” Conti said. “Most of the minor leagues is just having enough players so that these prospects can get at bats and innings. It’s sad. I just felt like I was playing baseball. It was a job, I was playing baseball as a job. it was better than getting a real job.”

But as Conti slowly moved his way up the professional ranks, the bright lights appeared much closer in the distance. He made his MLB debut for the Arizona Diamondbacks on Jun. 29, 2000, the start of a five-year major league career. In that span, Conti made appearances for the Diamondbacks, Devil Rays, Brewers and Rangers. He said he’d just advise players today to never take any chance for granted on your path to the majors.

“I used to get at-bats and it was 8-0 and I’d have to face a closer, and I remember maybe not seizing my opportunity to show, and I’d be like, ‘Why am I hitting right now?” Conti said. “But I’m hitting for a reason. They’re trying to evaluate me and see what I can do.”

Not everyone can reach the majors, of course — most players don’t. The decision to hang up the cleats for good can come at many different phases of a players’ trajectory, and former Pitt catcher Elvin Soto made it in a sudden fashion. The prime reason — to spend more time with his son.

“I was like ‘Hey man, I’m 25 years old in Double-A, sitting behind a guy who’s 23, who is a prospect and signed for a nice chunk of change,” Soto said. “Do I wanna keep playing every third day or do I wanna make some memories with my son?”

Soto made the sudden decision to retire from baseball in an effort to spend more time with his son, Bentley.

Two days after asking for his release, Soto’s agent called him to offer up a job within his organization. Now, he works as an MLBPA Certified Agent full-time, representing baseball players from the minors to the big leagues. He said one of the most important parts of his job is getting players to look at the bigger picture when they’re drafted, avoiding a false sense of security by making a financial plan for the future.

“The guy coming out of college or high school, they don’t understand that,” Soto said. “They just see ‘Hey, I play for the Pittsburgh Pirates,’ but we know, ‘Yeah, you play for the Pittsburgh Pirates, but you play for the Pittsburgh Pirates in West Virginia, and you’re making $1,200 before taxes. But the people in the stands, they don’t know that.”

Soto now watches his prospects from the stands as an MLBPA Certified Agent.

On the contrary, Conti didn’t wind up remaining within the sport after his playing days came to a close. The Pittsburgh native worked at Outback Steakhouse in Ross Park Mall at one point while he played in the minors, and he wound up staying in the food industry after he and his wife settled in Arizona. He’s currently a chef at Alo Cafe, a Eurostyle breakfast and lunch spot in Old Town Scottsdale.

“I really always liked cooking. I always cooked in the offseason,” Conti said. “I may be the only chef Major League Baseball player in the world, with a decent golf handicap.”

West, Fruere and Perry all hope to make the majors someday too, but their pursuits don’t end there. Getting to the top serves a major battle, but they see their potential as far more than just breaching the surface, with West mentioning a dependable starting role and Freure a Cy Young Award.

“I know I’m working a little bit against the clock — I’m 24 years old now, and then you’ve got three surgeries under my belt since 2016.” West said. “I’m behind the eight ball. I was in college, it’s not something I’m not accustomed to. I’m used to having my back against the wall.”

Overcoming failures hasn’t stopped Perry in the past either. The speedy outfielder was cut by his school’s first-year team, before leading his team to a WPIAL championship game as a senior. Cut by a Division II college program at the start of his college career, he begged for a spot on the roster of Lackawanna Community College’s team. He got that opportunity, and a few years later he’d earn All-ACC honors with the Panthers.

Perry wants to climb the baseball totem pole to give himself a greater platform to share his story, hoping it will inspire kids to not give up in their endeavors. He said the feeling would be “unimaginable” to play in a big league game after all the adversity he’s conquered throughout his career, but he only has one concern for that day.

“I just hope I get a hit in my first game,” Perry said. “That’s all I’m worried about.”