Pitt boasts rich track & field Olympic history

Image via University of Pittsburgh Library Archives

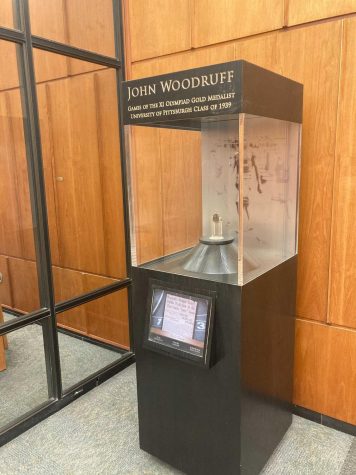

John Woodruff from Connellsville won a Gold Medal in the 1936 Olympics held in Berlin, Germany.

February 26, 2021

Pitt has produced scores of athletes whose determination and perseverance contributed to the school’s decorated history, but Pitt track and field may have the greatest record of success and impact, lasting decades after the achievements of its athletes.

When it comes to overcoming barriers, few have loomed larger than those that Black athletes encounter. They often compete in environments where their humanity is doubted, and their success is often downplayed. Greatness for Black athletes is always a moving target, but time and time again Pitt’s Black track and field athletes have stomped down these obstacles.

Four Pitt legends in particular — Herb Douglas, John Woodruff, Roger Kingdom and Trecia-Kaye Smith — dominated on and off the track, refusing to slow down for any hurdles thrown their way. They blazed trails for the competitors that came after them, and their names will live in Pitt lore forever.

Woodruff qualified for the 1936 Summer Olympics as a skinny first-year Pitt student. Woodruff, one of only 18 Black athletes to compete in Nazi Germany that year, wound up taking home an Olympic gold medal — one of only five to do so. His performance lives on with legendary status, as his tactics to win the 800 meter final included arguably one of the boldest strategies ever executed.

During the race, Woodruff found himself trapped in the inner lane by other runners. Instead of going through the crowd and risking disqualification for coming into contact with other runners, he paused to let the pack pass and then accelerated past the whole group in the last stretch of the race — one of the gutsiest maneuvers in Olympic history.

“I don’t have a chance of winning this race unless I get out of this box,” Woodruff said. “The only way I can get out of the box I felt was to slow down or stop.”

Woodruff showed tremendous fortitude to even make it to that stage. He trained to honor his country, at a time when he had to observe a disgustingly different set of laws than his teammates. He dominated the competition in a country where the ruling regime saw him as subhuman.

Woodruff’s gold medal sits on display on the first floor of the Hillman Library.

At those same games, Jesse Owens took home four Olympic medals in the sprints. His meteoric performance had a profound impact on future Pitt great Herb Douglas, who was 14 at the time. Seeing Owens compete at the highest level inspired Douglas to do the same. He excelled on the football field and the track in high school and eventually enrolled as an athlete at Pitt.

Known for his devastating speed on the football field, Douglas’ athletic talents shined the brightest in the long jump. Douglas would have been a likely selection for the 1944 games had they occured, but World War II put his Olympic aspirations on pause, and he continued to train diligently. Douglas recently took the time to encourage current Olympians who have been forced to delay competition in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As a 26-year-old, Douglas qualified for the 1948 London Olympic games. In his very first time abroad, Douglas did not shy away from the bright lights. He placed third in the long jump, and fulfilled his dream of competing in the Olympic games. At 98 years old, Douglas is the oldest living African American medalist.

Like Douglas, Kingdom excelled on the gridiron and the track, attending Pitt on a football scholarship in the early 1980s. He dominated the collegiate competition in his path, winning the 1983 NCAA indoor and outdoor national championships in the 110-meter hurdles, and the 1984 indoor championship for the 55-meter hurdles.

After his Pitt career concluded, Kingdom began obliterating international talent around the globe. He won two Olympic gold medals — one at the 1984 Los Angeles games and one at the 1988 Seoul games — becoming one of only two runners to ever win consecutive Olympic titles in the 110-meter hurdles.

Trecia-Kaye Smith competed much later than Woodruff, Douglas and Kingdom, but her tireless work ethic placed her in the same conversation of Pitt glory as all of them. Smith was one of the most prolific track and field athletes in NCAA history, winning seven NCAA titles and becoming a 15-time All-American. Her versatility in field events made her an extremely valuable member of the Pitt track and field team.

She went on to compete for Jamaica at the Olympic level in 2004, coming in fourth in the triple jump. The next year she became the first Jamaican woman to win a world championship title in a field event. She captured this title at the 2005 Helsinki world championship while battling through an ankle injury.

These athletes stories’ have been cemented into the Pitt Athletics Hall of Fame, contributing to Pitt’s reputation as a school that overcomes obstacles to achieve feats with longstanding impacts. Their legacies live on through storytelling and continued recognition within the Pittsburgh community, like Douglas recently receiving the Bob Imperata Passion for Pittsburgh Award.