‘Different voices’: Panel discusses Afro-Latinx history, new methods of teaching

Pitt’s Global Studies Center hosted a webinar titled “Transnational Dialogues in Afrolatinidad: Education and Anti-Blackness” on Friday afternoon. The webinar focused on how history, education and anti-Blackness impact Afro-Latin Americans and their communities, and how higher education can do more to teach this history.

March 8, 2021

For Solsiree Del Moral, there shouldn’t be a competition between understanding African and Latinx cultures. She said these topics — which are “traditionally placed in opposition to each other” — need to be reassessed in the higher education system.

“We need a broader historical understanding of the categories we’re reproducing today and whether or not we choose to narrow them and make them competitive or inclusive and historically informed,” Del Moral, a professor of American studies and Black studies at Amherst College, said.

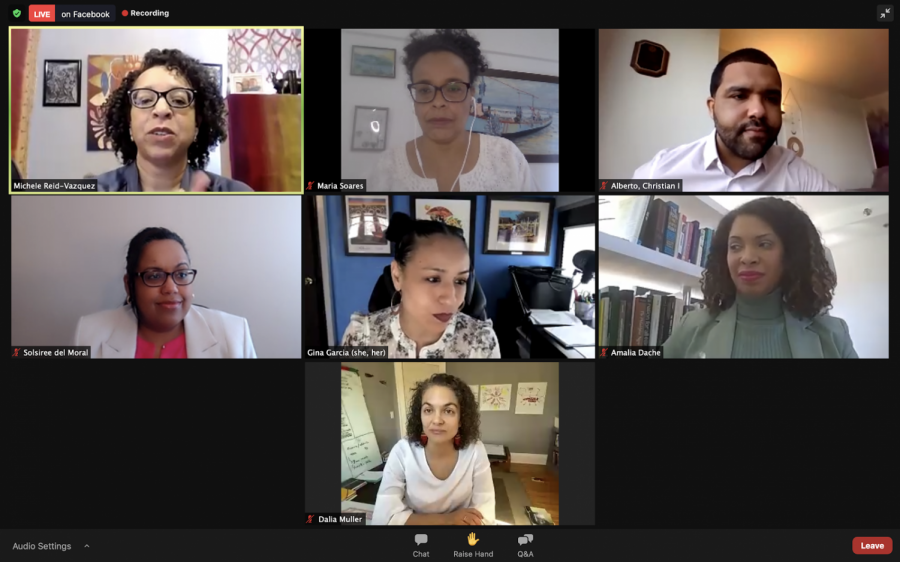

Pitt’s Global Studies Center hosted a webinar titled “Transnational Dialogues in Afrolatinidad: Education and Anti-Blackness” on Friday afternoon. The webinar — which was the third and final installment in the series “Transnational Dialogues in Afrolatinidad” — focused on how history, education and anti-Blackness impact Afro-Latin Americans and their communities, and how higher education can do more to teach this history.

Del Moral said in her presentation titled “Criminalized and Excluded: Black Children and Puerto Rico’s Institutions for Minors, 1910-1940” that the history of anti-Blackness in Puerto Rico has roots in the early 1900s — when Black youth were excluded from public and private education resources. She said during a time of increased homelessness on the island, institutions meant to house, protect and educate homeless children were mainly reserved for “white children.”

“Children of African descent, who may have been enumerated as either Black or mulatto or ‘colored’ according to the censuses, were either excluded entirely or criminalized and sent to the youth reformatory or adult jails and the island’s prison,” Del Moral said.

Del Moral said she observed these racial patterns through the use of the 1910-40 census data in Puerto Rico. She said the census provides key information about how children of color were excluded from social service and education resources during a time of economic crisis.

“The census is one way, although limited, to undo mythic nationalist narratives about racial harmony that silence the history of inequality and racialized childhoods, experienced by the most defenseless Puerto Ricans,” Del Moral said.

Amalia Dache, an associate professor in the higher education division at the University of Pennsylvania, also utilized census data to understand the proximity of and access to educational facilities for Latinx and Black populations in Philadelphia.

Dache said while students who identify as both Black and Latinx tended to want to attend more local colleges around Northern Philadelphia, students in more rural areas had less access to higher education institutes than urban areas.

Maria Soares, an associate professor at the University of the Afro-Brazilian Integration, discussed how — despite education being just as valued as public health in Brazil — people of color were excluded from education access. She said people of color were pushed out of the education system because of racially charged motives, such as wrongfully linking people of color in Brazil to crime and violence, or even learning problems.

“Many times, learning problems such as dyslexia, attention deficit or even health conditions such as hearing or vision impairments are not noticed and failed to be treated,” Soares said. “Meaning that Black kids with learning difficulties are criminalized and pushed out of school even before having their health conditions checked.”

Soares said, according to Brazilian census data, in 1991, only 8% of Brazilians were currently in or had finished college, with only 1.7% of that population being people of African descent. She said increasing the number of colleges and universities across rural areas of Brazil will help make higher education more accessible to all, and that Afro-Brazilian history can be taught more extensively in that higher education.

“Understanding that education is a public good must be assured to everybody, must reflect the reality of the Brazilian population, and must take into consideration the diversity of historical and cultural perspectives,” Soares said.

While the panelists presented historical connections between Black and Latinx populations and the effects of anti-Blackness on the population, they also highlighted how those in the education system, especially higher education, can become more aware of these issues by redefining how these subjects are taught.

Michele Reid-Vazquez, coordinator of the webinar and an associate professor of Africana Studies, spearheads Pitt’s approach to Black and Latinx studies. She created an “Afro-Latinx and the U.S.” course at Pitt about a year and a half ago and said the class has remained consistently full.

“It has really been amazing to see the kind of hunger that they have for this information,” Reid-Vazquez said. “They know it’s important, they know it’s critical and they’re searching actively for ways to incorporate that information into their world and into their perspective.”

Dalia Muller, an associate professor in the department of history at the University at Buffalo, said her project, the Impossible Project, aims to rethink Black and Latinx studies in the higher education system. Muller’s project involves a student-led “flipped classroom” where students are encouraged to address the large-scale global issue of anti-Blackness.

“The Impossible Project is grounded in theories drawn from the African diaspora and its thinkers,” Muller said. “And it instantiates the potential that those theories have in not just liberating Black people, but all people.”

Soares said real change in the classroom starts by recognizing other professors’ and scholars’ work on the subject of Black and Latinx populations, especially scholars who identify with this population. She said incorporating these scholars’ works into new curriculums and syllabi is a better approach to learning about these topics comprehensively.

“We’re having more professors committed to bringing different voices,” Soares said. “The voices of intellectuals from the African diaspora, the voices of intellectuals from the African continent and building new curriculums.”

As examples of important works to include in college curriculums, Del Moral suggested “Afro-Latin American Studies: An Introduction” by Alejandro de la Fuente and George Reid Andrews, a Pitt history professor, as well as “The Afro-Latin@ Reader” by Miriam Jiménez Román and Juan Flores. Del Moral said she incorporates these books into her Introduction to U.S. Afro-Latin America or Introduction to U.S. Afro-Latinx Studies courses.

Muller said “education is an inherently optimistic field” and the work that educators put into teaching about and representing the Afro-Latinx community is done to promote change in how people understand this culture.

“Those who dedicate ourselves to it [education] honestly and earnestly do so because we believe change is possible,” Muller said. “Because we believe changing how people think is possible, and more than that, because we believe that changing how people think about how they think enables them to think differently about who they are, about who they could be and about how they should be in this world.”